There are many fun yet highly educational therapy activities we can do with our preschool and school-aged clients in the fall. One of my personal favorites is bingo. Boggles World, an online ESL teacher resource actually has a number of ready-made materials, flashcards, and worksheets that can be adapted for speech-language therapy purposes. For example, their Fall and Halloween Bingo comes with both call out cards and a 3×3 and a 4×4 (as well as 3×3) card generator/boards. Clicking the refresh button will generate as many cards as you need, so the supply is endless! You can copy and paste the entire bingo board into a word document resize it and then print it out on reinforced paper or just laminate it. Continue reading Therapy Fun with Ready Made Fall and Halloween Bingo

There are many fun yet highly educational therapy activities we can do with our preschool and school-aged clients in the fall. One of my personal favorites is bingo. Boggles World, an online ESL teacher resource actually has a number of ready-made materials, flashcards, and worksheets that can be adapted for speech-language therapy purposes. For example, their Fall and Halloween Bingo comes with both call out cards and a 3×3 and a 4×4 (as well as 3×3) card generator/boards. Clicking the refresh button will generate as many cards as you need, so the supply is endless! You can copy and paste the entire bingo board into a word document resize it and then print it out on reinforced paper or just laminate it. Continue reading Therapy Fun with Ready Made Fall and Halloween Bingo

Category: multicultural

Using Picture Books to Teach Children That It’s OK to Make Mistakes and Take Risks

Those of you who follow my blog know that in my primary job as an SLP working for a psychiatric hospital, I assess and treat language and literacy impaired students with significant emotional and behavioral disturbances. I often do so via the aid of picture books (click HERE for my previous posts on this topic) dealing with a variety of social communication topics. Continue reading Using Picture Books to Teach Children That It’s OK to Make Mistakes and Take Risks

Those of you who follow my blog know that in my primary job as an SLP working for a psychiatric hospital, I assess and treat language and literacy impaired students with significant emotional and behavioral disturbances. I often do so via the aid of picture books (click HERE for my previous posts on this topic) dealing with a variety of social communication topics. Continue reading Using Picture Books to Teach Children That It’s OK to Make Mistakes and Take Risks

On the Disadvantages of Parents Ceasing to Speak the Birth Language with Bilingual Language Impaired Children

Despite significant advances in the fields of education and speech pathology, many harmful myths pertaining to multilingualism continue to persist. One particularly infuriating and patently incorrect recommendation to parents is the advice to stop speaking the birth language with their bilingual children with language disorders. Continue reading On the Disadvantages of Parents Ceasing to Speak the Birth Language with Bilingual Language Impaired Children

Despite significant advances in the fields of education and speech pathology, many harmful myths pertaining to multilingualism continue to persist. One particularly infuriating and patently incorrect recommendation to parents is the advice to stop speaking the birth language with their bilingual children with language disorders. Continue reading On the Disadvantages of Parents Ceasing to Speak the Birth Language with Bilingual Language Impaired Children

FREE Resources for Working with Russian Speaking Clients: Part II

A few years ago I wrote a blog post entitled “Working with Russian-speaking clients: implications for speech-language assessment” the aim of which was to provide some suggestions regarding assessment of bilingual Russian-American birth-school age population in order to assist SLPs with determining whether the assessed child presents with a language difference, insufficient language exposure, or a true language disorder.

Today I wanted to provide Russian speaking clinicians with a few FREE resources pertaining to the typical speech and language development of Russian speaking children 0-7 years of age.

Below materials include several FREE questionnaires regarding Russian language development (words and sentences) of children 0-3 years of age, a parent intake forms for Russian speaking clients, as well as a few relevant charts pertaining to the development of phonology, word formation, lexicon, morphology, syntax, and metalinguistics of children 0-7 years of age.

It is, however, important to note that due to the absence of research and standardized studies on this subject much of the below information still needs to be interpreted with significant caution.

Select Speech and Language Norms:

- Некоторые нормативы речевого развития детей от 18 до 36 месяцев (по материалам МакАртуровского опросника) (Number of words and sentence per age of Russian speakign children based on McArthur Bates)

- Речевой онтогенез: Развитие Речи Ребенка В Норме 0-7 years of age (based on the work of А.Н. Гвоздев) includes: Фонетика,Словообразование, Лексика, Морфолог-ия, Синтаксис, Метаязыковая деятельность (phonology, word formation, lexicon, morphology, syntax, and metalinguistics)

- Развитиe связной речи у детей 3-7 лет

a. Составление рассказа по серии сюжетных картинок

b. Пересказ текста

c. Составление описательного рассказа

Select Parent Questionnaires (McArthur Bates Adapted in Russian):

- Тест речевого и коммуникативного развития детей раннего возраста: слова и жесты (Words and Gestures)

- Тест речевого и коммуникативного развития детей раннего возраста: слова и предложения (Sentences)

- Анкета для родителей (Child Development Questionnaire for Parents)

Материал Для Родителей И Специалистов По Речевым

Нарушениям contains detailed information (27 pages) on Russian child development as well as common communication disrupting disorders

Stay tuned for more resources for Russian speaking SLPs coming shortly.

Related Resources:

- Working with Russian-speaking clients: implications for speech-language assessment

- Assessment of sound and syllable imitation in Russian speaking infants and toddlers

- Russian Articulation Screener

- Language Difference vs. Language Disorder: Assessment & Intervention Strategies for SLPs Working with Bilingual Children

- Impact of Cultural and Linguistic Variables On Speech-Language Services

New Products for the 2017 Academic School Year for SLPs

September is quickly approaching and school-based speech language pathologists (SLPs) are preparing to go back to work. Many of them are looking to update their arsenal of speech and language materials for the upcoming academic school year.

With that in mind, I wanted to update my readers regarding all the new products I have recently created with a focus on assessment and treatment in speech language pathology. Continue reading New Products for the 2017 Academic School Year for SLPs

Early Intervention Evaluations PART IV:Assessing Social Pragmatic Abilities of Children Under 3

To date, I have written 3 posts on speech and language assessments of children under 3 years of age. My first post offered suggestions on what information to include in general speech-language assessments for this age group, my second post specifically discussed assessments of toddlers with suspected motor speech disorders and my third post described what information I tend to include in reports for children ~16-18 months of age.

To date, I have written 3 posts on speech and language assessments of children under 3 years of age. My first post offered suggestions on what information to include in general speech-language assessments for this age group, my second post specifically discussed assessments of toddlers with suspected motor speech disorders and my third post described what information I tend to include in reports for children ~16-18 months of age.

Today, I’d like to offer some suggestions on the assessment of social emotional functioning and pragmatics of children, ages 3 and under.

For starters, below is the information I found compiled by a number of researchers on select social pragmatic milestones for the 0-3 age group:

- Peters, Kimberly (2013) Hierarchy of Social/Pragmatic Skills as Related to the Development of Executive Function

- Hutchins & Prelock, (2016) Select Social Cognitive Milestones from the Theory of Mind Atlas

3. Development of Theory of Mind (Westby, 2014)

In my social pragmatic assessments of the 0-3 population, in addition, to the child’s adaptive behavior during the assessment, I also describe the child’s joint attention, social emotional reciprocity, as well as social referencing abilities.

Joint attention is the shared focus of two individuals on an object. Responding to joint attention refers to the child’s ability to follow the direction of the gaze and gestures of others in order to share a common point of reference. Initiating joint attention involves child’s use of gestures and eye contact to direct others’ attention to objects, to events, and to themselves. The function of initiating joint attention is to show or spontaneously seek to share interests or pleasurable experience with others. (Mundy, et al, 2007)

Social emotional reciprocity involves being aware of the emotional and interpersonal cues of others, appropriately interpreting those cues, responding appropriately to what is interpreted as well as being motivated to engage in social interactions with others (LaRocque and Leach,2009).

Social referencing refers to a child’s ability to look at a caregiver’s cues such as facial expressions, body language and tone of voice in an ambiguous situation in order to obtain clarifying information. (Walden & Ogan, 1988)

Here’s a brief excerpt from an evaluation of a child ~18 months of age:

“RA’s joint attention skills, social emotional reciprocity as well as social referencing were judged to be appropriate for his age. For example, when Ms. N let in the family dog from the deck into the assessment room, RA immediately noted that the dog wanted to exit the room and go into the hallway. However, the door leading to the hallway was closed. RA came up to the closed door and attempted to reach the doorknob. When RA realized that he cannot reach to the doorknob to let the dog out, he excitedly vocalized to get Ms. N’s attention, and then indicated to her in gestures that the dog wanted to leave the room.”

If I happen to know that a child is highly verbal, I may actually include a narrative assessment, when evaluating toddlers in the 2-3 age group. Now, of course, true narratives do not develop in children until they are bit older. However, it is possible to limitedly assess the narrative abilities of verbal children in this age group. According to Hedberg & Westby (1993) typically developing 2-year-old children are at the Heaps Stage of narrative development characterized by

If I happen to know that a child is highly verbal, I may actually include a narrative assessment, when evaluating toddlers in the 2-3 age group. Now, of course, true narratives do not develop in children until they are bit older. However, it is possible to limitedly assess the narrative abilities of verbal children in this age group. According to Hedberg & Westby (1993) typically developing 2-year-old children are at the Heaps Stage of narrative development characterized by

- Storytelling in the form of a collection of unrelated ideas which consist of labeling and describing events

- Frequent switch of topic is evident with lack of central theme and cohesive devices

- The sentences are usually simple declarations which contain repetitive syntax and use of present or present progressive tenses

- In this stage, children possess limited understanding that the character on the next page is still same as on the previous page

In contrast, though typically developing children between 2-3 years of age in the Sequences Stage of narrative development still arbitrarily link story elements together without transitions, they can:

- Label and describe events about a central theme with stories that may contain a central character, topic, or setting

To illustrate, below is a narrative sample from a typically developing 2-year-old child based on the Mercer Mayer’s classic wordless picture book: “Frog Where Are You?”

To illustrate, below is a narrative sample from a typically developing 2-year-old child based on the Mercer Mayer’s classic wordless picture book: “Frog Where Are You?”

- He put a froggy in there

- He’s sleeping

- Froggy came out

- Where did did froggy go?

- Now the dog fell out

- Then he got him

- You are a silly dog

- And then

- where did froggy go?

- In in there

- Up up into the tree

- Up there an owl

- Froggy

- A reindeer caught him

- Then he dropped him

- Then he went into snow

- And then he cleaned up that

- Then stopped right there and see what wha wha wha what he found

- He found two froggies

- They lived happily ever after

Of course, a play assessment for this age group is a must. Since, in my first post, I offered a play skills excerpt from one of my early intervention assessments and in my third blog post, I included a link to the Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000), I will now move on to the description of a few formal instruments I find very useful for this age group.

Of course, a play assessment for this age group is a must. Since, in my first post, I offered a play skills excerpt from one of my early intervention assessments and in my third blog post, I included a link to the Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000), I will now move on to the description of a few formal instruments I find very useful for this age group.

While some criterion-referenced instruments such as the Rossetti, contain sections on Interaction-Attachment and Pragmatics, there are other assessments which I prefer for evaluating social cognition and pragmatic abilities of toddlers.

For toddlers 18+months of age, I like using the Language Use Inventory (LUI) (O’Neill, 2009) which is administered in the form of a parental questionnaire that can be completed in approximately 20 minutes. Aimed at identifying children with delay/impairment in pragmatic language development it contains 180 questions and divided into 3 parts and 14 subscales including:

For toddlers 18+months of age, I like using the Language Use Inventory (LUI) (O’Neill, 2009) which is administered in the form of a parental questionnaire that can be completed in approximately 20 minutes. Aimed at identifying children with delay/impairment in pragmatic language development it contains 180 questions and divided into 3 parts and 14 subscales including:

- Communication w/t gestures

- Communication w/t words

- Longer sentences

Therapists can utilize the Automated Score Calculator, which accompanies the LUI in order to generate several pages write up or summarize the main points of the LUI’s findings in their evaluation reports.

Below is an example of a summary I wrote for one of my past clients, 35 months of age.

AN’s ability to use language was assessed via the administration of the Language Use Inventory (LUI). The LUI is a standardized parental questionnaire for children ages 18-47 months aimed at identifying children with delay/impairment in pragmatic language development. Composed of 3 parts and 14 subscales it focuses on how the child communicates with gestures, words and longer sentences.

On the LUI, AN obtained a raw score of 53 and a percentile rank of <1, indicating profoundly impaired performance in the area of language use. While AN scored in the average range in the area of varied word use, deficits were noted with requesting help, word usage for notice, lack of questions and comments regarding self and others, lack of reciprocal word usage in activities with others, humor relatedness, adapting to conversations to others, as well as difficulties with building longer sentences and stories.

Based on above results AN presents with significant social pragmatic language weaknesses characterized by impaired ability to use language for a variety of language functions (initiate, comment, request, etc), lack of reciprocal word usage in activities with others, humor relatedness, lack of conversational abilities, as well as difficulty with spontaneous sentence and story formulation as is appropriate for a child his age. Therapeutic intervention is strongly recommended to improve AN’s social pragmatic abilities.

In addition to the LUI, I recently discovered the Theory of Mind Inventory-2. The ToMI-2 was developed on a normative sample of children ages 2 – 13 years. For children between 2-3 years of age, it offers a 14 question Toddler Screen (shared here with author’s permission). While due to the recency of my discovery, I have yet to use it on an actual client, I did have fun creating a report with it on a fake client.

In addition to the LUI, I recently discovered the Theory of Mind Inventory-2. The ToMI-2 was developed on a normative sample of children ages 2 – 13 years. For children between 2-3 years of age, it offers a 14 question Toddler Screen (shared here with author’s permission). While due to the recency of my discovery, I have yet to use it on an actual client, I did have fun creating a report with it on a fake client.

First, I filled out the online version of the 14 question Toddler Screen (paper version embedded in the link above for illustration purposes). Typically the parents are asked to place slashes on the form in relevant areas, however, the online version requested that I use numerals to rate skill acquisition, which is what I had done. After I had entered the data, the system generated a relevant report for my imaginary client. In addition to the demographic section, the report generated the following information (below):

- A bar graph of the client’s skills breakdown in the developed, undecided and undeveloped ranges of the early ToM development scale.

- Percentile scores of how the client did in the each of the 14 early ToM measures

- Median percentiles of scores

- Table for treatment planning broken down into strengths and challenges

I find the information provided to me by the Toddler Screen highly useful for assessment and treatment planning purposes and definitely have plans on using this portion of the TOM-2 Inventory as part of my future toddler evaluations.

Of course, the above instruments are only two of many, aimed at assessing social pragmatic abilities of children under 3 years of age, so I’d like to hear from you! What formal and informal instruments are you using to assess social pragmatic abilities of children under 3 years of age? Do you have a favorite one, and if so, why do you like it?

References:

- Hedberg, N.L., & Westby, C.E. (1993). Analyzing story-telling skills: Theory to practice. AZ: Communication Skill Builders.

- Mundy P, Block J, Delgado C, Pomares Y, Vaughan Van Hecke A, Parlade MV. (2007) Individual Differences and the Development of Joint Attention in Infancy. Child Development. 78:938–954

- LaRocque, M., & Leach, D. (2009). Increasing social reciprocity in young children with Autism. Intervention in School and Clinic, 10(5), 1-7.

- O’Neill, D. (2009). Language Use Inventory: An assessment of young children’s pragmatic language development for 18- to 47-month-old children [Manual]. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada Knowledge in Development

- Tomasello, M. (1995). Joint attention as social cognition. In C. Moore, & P. J. Dunham (Eds.), Joint attention: It’s origins and role in development (pp. 103–130). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Walden, T., & Ogan, T. (1988). The development of social referencing. Child Development, 59, 1230-1240.

- Westby, C. & Robinson, L. (2014). A developmental perspective for promoting theory of mind. Topics in

Language Disorders, 34(4), 362-383.

Is it a Difference or a Disorder? Free Resources for SLPs Working with Bilingual and Multicultural Children

For bilingual and monolingual SLPs working with bilingual and multicultural children, the question of: “Is it a difference or a disorder?” arises on a daily basis as they attempt to navigate the myriad of difficulties they encounter in their attempts at appropriate diagnosis of speech, language, and literacy disorders.

For bilingual and monolingual SLPs working with bilingual and multicultural children, the question of: “Is it a difference or a disorder?” arises on a daily basis as they attempt to navigate the myriad of difficulties they encounter in their attempts at appropriate diagnosis of speech, language, and literacy disorders.

For that purpose, I’ve recently created a Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children. Its aim is to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) and Teachers in the decision-making process of how to appropriately identify bilingual/multicultural children who present with speech-language delay/deficits (vs. a language difference), for the purpose of initiating a formal speech-language-literacy evaluation. The goal is to ensure that educational professionals are appropriately identifying bilingual children for assessment and service provision due to legitimate speech language deficits/concerns, and are not over-identifying students because they speak multiple languages or because they come from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It is very important to understand that true language impairment in bilingual children will be evident in both languages from early childhood onwards, and thus will adversely affect the learning of both languages.

For that purpose, I’ve recently created a Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children. Its aim is to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) and Teachers in the decision-making process of how to appropriately identify bilingual/multicultural children who present with speech-language delay/deficits (vs. a language difference), for the purpose of initiating a formal speech-language-literacy evaluation. The goal is to ensure that educational professionals are appropriately identifying bilingual children for assessment and service provision due to legitimate speech language deficits/concerns, and are not over-identifying students because they speak multiple languages or because they come from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It is very important to understand that true language impairment in bilingual children will be evident in both languages from early childhood onwards, and thus will adversely affect the learning of both languages.

However, today the aim of today’s post is not on the above product but rather on the FREE free bilingual and multicultural resources available to SLPs online in their quest of differentiating between a language difference from a language disorder in bilingual and multicultural children.

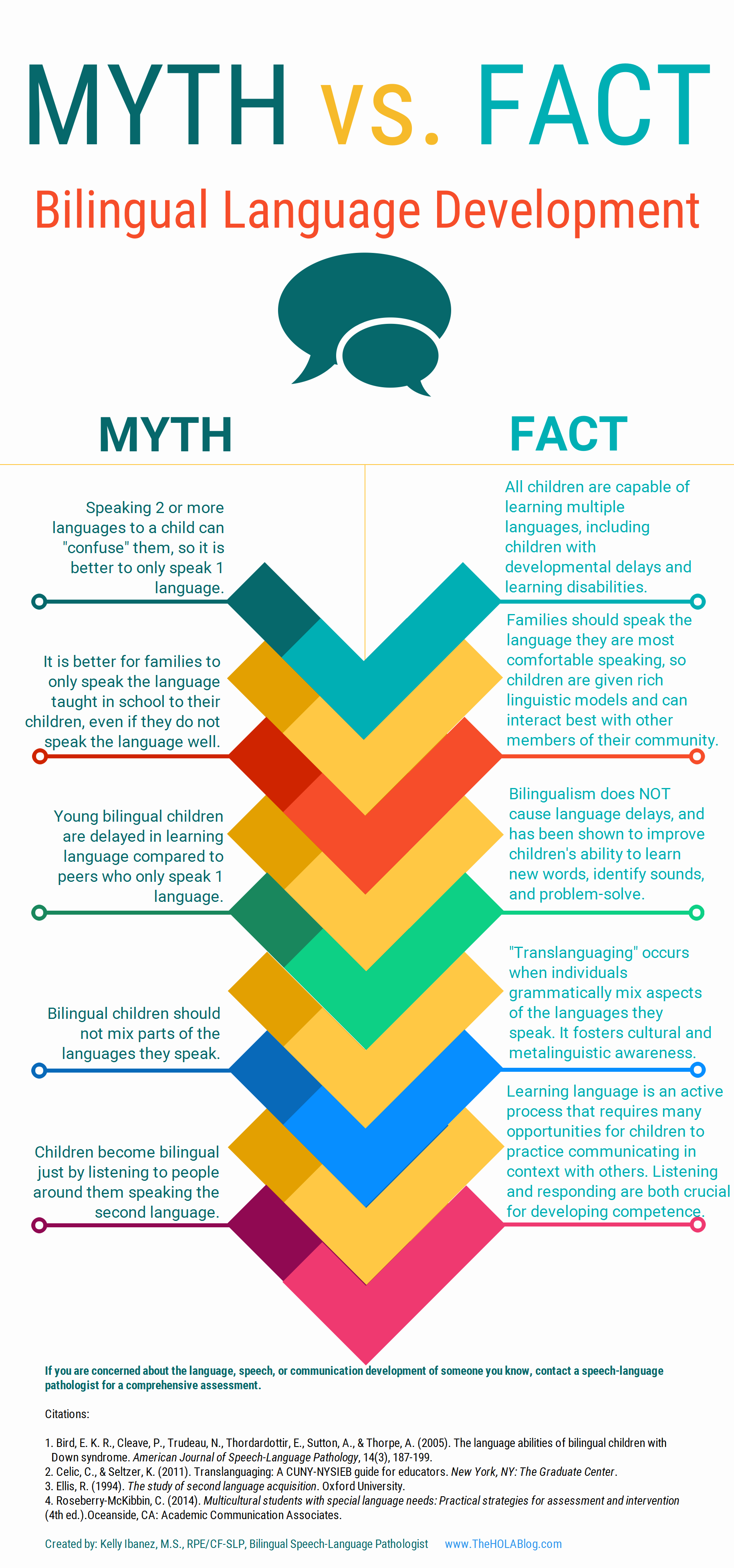

Let’s start with an excellent free infographic entitled from the Hola Blog “Myth vs. Fact: Bilingual Language Development” which was created by Kelly Ibanez, MS CCC-SLP to help dispel bilingual myths and encourage practices that promote multilingualism. Clinicians can download it and refer to it themselves, share it with other health and/or educational professionals as well as show it to parents of their clients.

Let’s start with an excellent free infographic entitled from the Hola Blog “Myth vs. Fact: Bilingual Language Development” which was created by Kelly Ibanez, MS CCC-SLP to help dispel bilingual myths and encourage practices that promote multilingualism. Clinicians can download it and refer to it themselves, share it with other health and/or educational professionals as well as show it to parents of their clients.

Let us now move on to the typical phonological development of English speaking children. After all, in order to compare other languages to English, SLPs need to be well versed in the acquisition of speech sounds in the English language. Children’s speech acquisition, developed by Sharynne McLeod, Ph.D., of Charles Sturt University, is one such resource. It contains a compilation of data on typical speech development for English speaking children, which is organized according to children’s ages to reflect a typical developmental sequence.

Next up, is a great archive which contains phonetic inventories of the various language spoken around the world for contrastive analysis purposes. The same website also contains a speech accent archive. Native and non-native speakers of English were recorded reading the same English paragraph for teaching and research purposes. It is meant to be used by professionals who are interested in comparing the accents of different English speakers.

Next up, is a great archive which contains phonetic inventories of the various language spoken around the world for contrastive analysis purposes. The same website also contains a speech accent archive. Native and non-native speakers of English were recorded reading the same English paragraph for teaching and research purposes. It is meant to be used by professionals who are interested in comparing the accents of different English speakers.

![]() Now let’s talk about one of my favorite websites, MULTILINGUAL CHILDREN’S SPEECH, also developed by Dr. Mcleod of Charles Stuart University. It contains an AMAZING plethora of resources on bilingual speech development and assessment. To illustrate, its Speech Acquisition Data includes A list of over 200 speech acquisition studies. It also contains a HUGE archive on Speech Assessments in NUMEROUS LANGUAGES as well as select assessment reviews. Finally, the website also lists in detail how aspects of speech (e.g., consonants, vowels, syllables, tones) differ between languages.

Now let’s talk about one of my favorite websites, MULTILINGUAL CHILDREN’S SPEECH, also developed by Dr. Mcleod of Charles Stuart University. It contains an AMAZING plethora of resources on bilingual speech development and assessment. To illustrate, its Speech Acquisition Data includes A list of over 200 speech acquisition studies. It also contains a HUGE archive on Speech Assessments in NUMEROUS LANGUAGES as well as select assessment reviews. Finally, the website also lists in detail how aspects of speech (e.g., consonants, vowels, syllables, tones) differ between languages.

The Leader’s Project Website is another highly informative source of FREE information on bilingual assessments, intervention, and FREE CEUS.

Now, I’d like to list some resources regarding language transfer errors.

This chart from Cengage Learning contains a nice, concise Language Guide to Transfer Errors. While it is aimed at multilingual/ESL writers, the information contained on the site is highly applicable to multilingual speakers as well.

You can also find a bonus transfer chart HERE. It contains information on specific structures such as articles, nouns, verbs, pronouns, adverbs, adjectives, word order, questions, commands, and negatives on pages 1-6 and phonemes on pages 7-8.

A final bonus chart entitled: Teacher’s Resource Guide of Language Transfer Issues for English Language Learners containing information on grammar and phonics for 10 different languages can be found HERE.

Similarly, this 16-page handout: Language Transfers: The Interaction Between English and Students’ Primary Languages also contains information on phonics and grammar transfers for Spanish, Cantonese, Vietnamese, Hmong Korean, and Khmer languages.

For SLPs working with Russian-speaking children the following links pertinent to assessment, intervention and language transference may be helpful:

For SLPs working with Russian-speaking children the following links pertinent to assessment, intervention and language transference may be helpful:

- Working with Russian-speaking clients: implications for speech-language assessment

- Strategies in the acquisition of segments and syllables in Russian-speaking children

- Language Development of Bilingual Russian/ English Speaking Children Living in the United States: A Review of the Literature

- The acquisition of syllable structure by Russian-speaking children with SLI

To determine information about the children’s language development and language environment, in both their first and second language, visit the CHESL Centre website for The Alberta Language Development Questionnaire and The Alberta Language Environment Questionnaire

There you have it! FREE bilingual/multicultural SLP resources compiled for you conveniently in one place. And since there are much more FREE GEMS online, I’d love it if you guys contributed to and expanded this modest list by posting links and title descriptions in the comments section below for others to benefit from!

Together we can deliver the most up to date evidence-based assessment and intervention to bilingual and multicultural students that we serve! Click HERE to check out the FREE Resources in the SLPs for Evidence-Based Practice Group

Helpful Bilingual Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

- Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children

- Multicultural Assessment Bundle

- Best Practices in Bilingual Literacy Assessments and Interventions

- Dynamic Assessment of Bilingual and Multicultural Learners in Speech-Language Pathology

- Practical Strategies for Monolingual SLPs Assessing and Treating Bilingual Children

- Language Difference vs. Language Disorder: Assessment & Intervention Strategies for SLPs Working with Bilingual Children

- Impact of Cultural and Linguistic Variables On Speech-Language Services

- Assessment of sound and syllable imitation in Russian-speaking infants and toddlers

- Russian Articulation Screener

- Creating Translanguaging Classrooms and Therapy Rooms

A Focus on Literacy

In recent months, I have been focusing more and more on speaking engagements as well as the development of products with an explicit focus on assessment and intervention of literacy in speech-language pathology. Today I’d like to introduce 4 of my recently developed products pertinent to assessment and treatment of literacy in speech-language pathology.

In recent months, I have been focusing more and more on speaking engagements as well as the development of products with an explicit focus on assessment and intervention of literacy in speech-language pathology. Today I’d like to introduce 4 of my recently developed products pertinent to assessment and treatment of literacy in speech-language pathology.

First up is the Comprehensive Assessment and Treatment of Literacy Disorders in Speech-Language Pathology

First up is the Comprehensive Assessment and Treatment of Literacy Disorders in Speech-Language Pathology

which describes how speech-language pathologists can effectively assess and treat children with literacy disorders, (reading, spelling, and writing deficits including dyslexia) from preschool through adolescence. It explains the impact of language disorders on literacy development, lists formal and informal assessment instruments and procedures, as well as describes the importance of assessing higher order language skills for literacy purposes. It reviews components of effective reading instruction including phonological awareness, orthographic knowledge, vocabulary awareness, morphological awareness, as well as reading fluency and comprehension. Finally, it provides recommendations on how components of effective reading instruction can be cohesively integrated into speech-language therapy sessions in order to improve literacy abilities of children with language disorders and learning disabilities.

Next up is a product entitled From Wordless Picture Books to Reading Instruction: Effective Strategies for SLPs Working with Intellectually Impaired Students. This product discusses how to address the development of critical thinking skills through a variety of picture books utilizing the framework outlined in Bloom’s Taxonomy: Cognitive Domain which encompasses the categories of knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation in children with intellectual impairments. It shares a number of similarities with the above product as it also reviews components of effective reading instruction for children with language and intellectual disabilities as well as provides recommendations on how to integrate reading instruction effectively into speech-language therapy sessions.

Next up is a product entitled From Wordless Picture Books to Reading Instruction: Effective Strategies for SLPs Working with Intellectually Impaired Students. This product discusses how to address the development of critical thinking skills through a variety of picture books utilizing the framework outlined in Bloom’s Taxonomy: Cognitive Domain which encompasses the categories of knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation in children with intellectual impairments. It shares a number of similarities with the above product as it also reviews components of effective reading instruction for children with language and intellectual disabilities as well as provides recommendations on how to integrate reading instruction effectively into speech-language therapy sessions.

The product Improving Critical Thinking Skills via Picture Books in Children with Language Disorders is also available for sale on its own with a focus on only teaching critical thinking skills via the use of picture books.

The product Improving Critical Thinking Skills via Picture Books in Children with Language Disorders is also available for sale on its own with a focus on only teaching critical thinking skills via the use of picture books.

Finally, my last product Best Practices in Bilingual Literacy Assessments and Interventions focuses on how bilingual speech-language pathologists (SLPs) can effectively assess and intervene with simultaneously bilingual and multicultural children (with stronger academic English language skills) diagnosed with linguistically-based literacy impairments. Topics include components of effective literacy assessments for simultaneously bilingual children (with stronger English abilities), best instructional literacy practices, translanguaging support strategies, critical questions relevant to the provision of effective interventions, as well as use of accommodations, modifications and compensatory strategies for improvement of bilingual students’ performance in social and academic settings.

Finally, my last product Best Practices in Bilingual Literacy Assessments and Interventions focuses on how bilingual speech-language pathologists (SLPs) can effectively assess and intervene with simultaneously bilingual and multicultural children (with stronger academic English language skills) diagnosed with linguistically-based literacy impairments. Topics include components of effective literacy assessments for simultaneously bilingual children (with stronger English abilities), best instructional literacy practices, translanguaging support strategies, critical questions relevant to the provision of effective interventions, as well as use of accommodations, modifications and compensatory strategies for improvement of bilingual students’ performance in social and academic settings.

You can find these and other products in my online store (HERE).

Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

- Dynamic Assessment of Bilingual and Multicultural Learners in Speech-Language Pathology

- Differential Assessment and Treatment of Processing Disorders in Speech-Language Pathology

- Practical Strategies for Monolingual SLPs Assessing and Treating Bilingual Children

- The Checklists Bundle

- General Assessment and Treatment Start Up Bundle

- Multicultural Assessment Bundle

- Narrative Assessment and Treatment Bundle

- Social Pragmatic Assessment and Treatment Bundle

- Psychiatric Disorders Bundle

Dear SLPs, Here’s What You Need to Know About Internationally Adopted Children

In the past several years there has been a sharp decline in international adoptions. Whereas in 2004, Americans adopted a record high of 22,989 children from overseas, in 2015, only 5,647 children (a record low in 30 years) were adopted from abroad by American citizens.

In the past several years there has been a sharp decline in international adoptions. Whereas in 2004, Americans adopted a record high of 22,989 children from overseas, in 2015, only 5,647 children (a record low in 30 years) were adopted from abroad by American citizens.

Primary Data Source: Data Source: U.S. State Department Intercountry Adoption Statistics

Secondary Data Source: Why Did International Adoption Suddenly End?

Despite a sharp decline in adoptions many SLPs still frequently continue to receive internationally adopted (IA) children for assessment as well as treatment – immediately post adoption as well as a number of years post-institutionalization.

In the age of social media, it may be very easy to pose questions and receive instantaneous responses on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter with respect to assessment and treatment recommendations. However, it is very important to understand that many SLPs, who lack direct clinical experience in international adoptions may chime in with inappropriate recommendations with respect to the assessment or treatment of these children.

Consequently, it is important to identify reputable sources of information when it comes to speech-language assessment of internationally adopted children.

There are a number of researchers in both US and abroad who specialize in speech-language abilities of Internationally Adopted children. This list includes (but is by far not limited to) the following authors:

- Boris Gindis

- Sharon Glennen

- Deborah Hwa-Froelich

- Kathleen A. Scott

- Jenny A. Roberts

- Karen E. Pollock

- M. Gay Masters

- Monica Dalen

The works of these researchers can be readily accessed in the ASHA Journals or via ResearchGate.

Meanwhile, here are some basic facts regarding internationally adopted children that all SLPs and parents need to know.

Demographics:

- A greater number of older, preschool and school-aged children and fewer number of infants and toddlers are placed for adoption (Selman, 2012).

- Significant increase in special needs adoptions from Eastern European countries (e.g., Ukraine, Kazhakstan, etc.) as well as China. The vast majority of Internationally Adopted children arrive to the United States with significant physical, linguistic, and cognitive disabilities as well as mental health problems. Consequently, it is important for schools to immediately provide the children with a host of services including speech-language therapy, immediately post-arrival.

- It is also important to know that in the vast majority of cases the child’s linguistic, cognitive, or mental health deficits may not be documented in the adoption records due to poor record keeping, lack of access to adequate healthcare or often to ensure their “adoptability”. As such, parental interviews and anecdotal evidence become the primary source of information regarding these children’s social and academic functioning in their respective birth countries.

The question of bilingualism:

- Internationally Adopted children are NOT bilingual children! In fact, the vast majority of internationally adopted children will very rapidly lose their birth language, in a period of 2-3 months post arrival (Gindis, 2005), since they are most often adopted by parents who do not speak the child’s birth language and as such are unable/unwilling to maintain it.

- IA children do not need to be placed in ESL classes since they are not bilingual children. Not only are IA children not bilingual, they are also not ‘truly’ monolingual since their first language is lost rather rapidly, while their second language has been gained minimally at the time of loss.

- IA children need to acquire Cognitive Language Mastery (CLM) which is language needed for formal academic learning. This includes listening, speaking, reading, and writing about subject area content material including analyzing, synthesizing, judging and evaluating presented information. This level of language learning is essential for a child to succeed in school. CLM takes years and years to master, especially because, IA children did not have the same foundation of knowledge and stimulation as bilingual children in their birth countries.

Assessment Parameters:

- IA children’s language abilities should be retested and monitored at regular intervals during the first several years post arrival.

- Glennen (2007) recommends 3 evaluations during the first year post arrival, with annual reevaluations thereafter.

- Hough & Kaczmarek (2011) recommend a reevaluation schedule of 3-4 times a year for a period of two years, post arrival because some IA children continue to present with language-based deficits many years (5+) post-adoption.

- If an SLP speaking the child’s first language is available the window of opportunity to assess in the first language is very limited (~2-3 months at most).

- Similarly, an assessment with an interpreter is recommended immediately post arrival from the birth country for a period of approximately the same time.

- If an SLP speaking the child’s first language is not available English-speaking SLP should consider assessing the child in English between 3-6 months post arrival (depending on the child and the situational constraints) in order to determine the speed with which s/he are acquiring English language abilities

- Children should be demonstrating rapid language gains in the areas of receptive language, vocabulary as well as articulation (Glennen 2007, 2009)

- Dynamic assessment is highly recommended

- It is important to remember that language and literacy deficits are not always very apparent and can manifest during any given period post arrival

To treat or NOT to Treat?

- “Any child with a known history of speech and language delays in the sending country should be considered to have true delays or disorders and should receive speech and language services after adoption.” (Glennen, 2009, p.52)

- IA children with medical diagnoses, which impact their speech language abilities should be assessed and considered for S-L therapy services as well (Ladage, 2009).

Helpful Links:

- Elleseff, T (2013) Changing Trends in International Adoption: Implications for Speech-Language Pathologists. Perspectives on Global Issues in Communication Sciences and Related Disorders, 3: 45-53

- Assessing Behaviorally Impaired Students: Why Background History Matters!

- Dear School Professionals Please Be Aware of This

- What parents need to know about speech-language assessment of older internationally adopted children

- Understanding the risks of social pragmatic deficits in post institutionalized internationally adopted (IA) children

- Understanding the extent of speech and language delays in older internationally adopted children

References:

- Gindis, B. (2005). Cognitive, language, and educational issues of children adopted from overseas orphanages. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 4 (3): 290-315.

- Glennen, S (2009) Speech and language guidelines for children adopted from abroad at older ages. Topics in language Disorders 29, 50-64.

- Ladage, J. S. (2009). Medical Issues in International Adoption and Their Influence on Language Development. Topics in Language Disorders , 29 (1), 6-17.

- Selman P. (2012) Global trends in Intercountry Adoption 2000-2010. New York: National Council for Adoption, 2012.

- Selman P. The global decline of intercountry adoption: What lies ahead?. Social Policy and Society 2012, 11(3), 381-397.

Additional Helpful References:

- Abrines, N., Barcons, N., Brun, C., Marre, D., Sartini, C., & Fumadó, V. (2012). Comparing ADHD symptom levels in children adopted from Eastern Europe and from other regions: discussing possible factors involved. Children and Youth Services Review, 34 (9) 1903-1908.

- Balachova, T et al (2010). Changing physicians’ knowledge, skills and attitudes to prevent FASD in Russia: 800. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 34(6) Sup 2:210A.

- Barcons-Castel, N, Fornieles-Deu,A, & Costas-Moragas, C (2011). International adoption: assessment of adaptive and maladaptive behavior of adopted minors in Spain. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 14 (1): 123-132.

- Beverly, B., McGuinness, T., & Blanton, D. (2008). Communication challenges for children adopted from the former Soviet Union. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 39, 1-11.

- Cohen, N. & Barwick, M. (1996). Comorbidity of language and social-emotional disorders: comparison of psychiatric outpatients and their siblings. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(2), 192-200.

- Croft, C et al, (2007). Early adolescent outcomes of institutionally-deprived and nondeprived adoptees: II. Language as a protective factor and a vulnerable outcome. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 31–44.

- Dalen, M. (2001). School performances among internationally adopted children in Norway. Adoption Quarterly, 5(2), 39-57.

- Dalen, M. (1995). Learning difficulties among inter-country adopted children. Nordisk pedagogikk, 15 (No. 4), 195-208

- Davies, J., & Bledsoe, J. (2005). Prenatal alcohol and drug exposures in adoption. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 52, 1369–1393.

- Desmarais, C., Roeber, B. J., Smith, M. E., & Pollak, S. D. (2012). Sentence comprehension in post-institutionalized school-age children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 55, 45-54

- Eigsti, I. M., Weitzman, C., Schuh, J. M., de Marchena, A., & Casey, B. J. (2011). Language and cognitive outcomes in internationally adopted children. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 629-646.

- Geren, J., Snedeker, J., & Ax, L. (2005). Starting over: a preliminary study of early lexical and syntactic development in internationally-adopted preschoolers. Seminars in Speech & Language, 26:44-54.

- Gindis (2008) Abrupt native language loss in international adoptees. Advance for Speech/Language Pathologists and Audiologists. 18(51): 5.

- Gindis, B. (2005). Cognitive, language, and educational issues of children adopted from overseas orphanages. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 4 (3): 290-315. Gindis, B. (1999) Language-related issues for international adoptees and adoptive families. In: T. Tepper, L. Hannon, D. Sandstrom, Eds. “International Adoption: Challenges and Opportunities.” PNPIC, Meadow Lands , PA. , pp. 98-108

- Glennen, S (2009) Speech and language guidelines for children adopted from abroad at older ages. Topics in language Disorders 29, 50-64.

- Glennen, S. (2007) Speech and language in children adopted internationally at older ages. Perspectives on Communication Disorders in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations, 14, 17–20.

- Glennen, S., & Bright, B. J. (2005). Five years later: language in school-age internally adopted children. Seminars in Speech and Language, 26, 86-101.

- Glennen, S. & Masters, G. (2002). Typical and atypical language development in infants and toddlers adopted from Eastern Europe. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 44, 417-433

- Gordina, A (2009) Parent Handout: The Dream Referral, Unpublished Manuscript.

- Hough, S., & Kaczmarek, L. (2011). Language and reading outcomes in young children adopted from Eastern European orphanages. Journal of Early Intervention, 33, 51-57.

- Hwa-Froelich, D (2012) Childhood maltreatment and communication development. Perspectives on School-Based Issues, 13: 43-53;

- Jacobs, E., Miller, L. C., & Tirella, G. (2010). Developmental and behavioral performance of internationally adopted preschoolers: a pilot study. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41, 15–29.

- Jenista, J., & Chapman, D. (1987). Medical problems of foreign-born adopted children. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 141, 298–302.

- Johnson, D. (2000). Long-term medical issues in international adoptees. Pediatric Annals, 29, 234–241.

- Judge, S. (2003). Developmental recovery and deficit in children adopted from Eastern European orphanages. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 34, 49–62.

- Krakow, R. A., & Roberts, J. (2003). Acquisitions of English vocabulary by young Chinese adoptees. Journal of Multilingual Communication Disorders, 1, 169-176

- Ladage, J. S. (2009). Medical issues in international adoption and their influence on language development. Topics in Language Disorders , 29 (1), 6-17.

- Loman, M. M., Wiik, K. L., Frenn, K. A., Pollak, S. D., & Gunnar, M. R. (2009). Post-institutionalized children’s development: growth, cognitive, and language outcomes. Journal of Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, 30, 426–434.

- McLaughlin, B., Gesi Blanchard, A., & Osanai, Y. (1995). Assessing language development in bilingual preschool children. Washington, D.C.: National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education.

- Miller, L., Chan, W., Litvinova, A., Rubin, A., Tirella, L., & Cermak, S. (2007). Medical diagnoses and growth of children residing in Russian orphanages. Acta Paediatrica, 96, 1765–1769.

- Miller, L., Chan, W., Litvinova, A., Rubin, A., Comfort, K., Tirella, L., et al. (2006). Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in children residing in Russian orphanages: A phenotypic survey. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 30, 531–538.

- Miller, L. (2005). Preadoption counseling and evaluation of the referral. In L. Miller (Ed.), The Handbook of International Adoption Medicine (pp. 67-86). NewYork: Oxford.

- Pollock, K. E. (2005) Early language growth in children adopted from China: preliminary normative data. Seminars in Speech and Language, 26, 22-32.

- Roberts, J., Pollock, K., Krakow, R., Price, J., Fulmer, K., & Wang, P. (2005). Language development in preschool-aged children adopted from China. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48, 93–107.

- Scott, K.A., Roberts, J.A., & Glennen, S. (2011). How well children who are internationally do adopted acquire language? A meta-analysis. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 54. 1153-69.

- Scott, K.A., & Roberts, J. (2011). Making evidence-based decisions for children who are internationally adopted. Evidence-Based Practice Briefs. 6(3), 1-16.

- Scott, K.A., & Roberts, J. (2007) language development of internationally adopted children: the school-age years. Perspectives on Communication Disorders in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations, 14: 12-17.

- Selman P. (2012a) Global trends in intercountry adoption 2000-2010. New York: National Council for Adoption.

- Selman P (2012b). The rise and fall of intercountry adoption in the 21st century. In: Gibbons, J.L., Rotabi, K.S, ed. Intercountry Adoption: Policies, Practices and Outcomes. London: Ashgate Press.

- Selman, P. (2010) “Intercountry adoption in Europe 1998–2009: patterns, trends and issues,” Adoption & Fostering, 34 (1): 4-19.

- Silliman, E. R., & Scott, C. M. (2009). Research-based oral language intervention routes to the academic language of literacy: Finding the right road. In S. A. Rosenfield & V. Wise Berninger (Eds.), Implementing evidence-based academic interventions in school (pp. 107–145). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tarullo, A. R., Bruce, J., & Gunnar, M. (2007). False belief and emotion understanding in post-institutionalized children. Social Development, 16, 57-78

- Tarullo, A. & Gunnar, M. R. (2005). Institutional rearing and deficits in social relatedness: Possible mechanisms and processes. Cognitie, Creier, Comportament [Cognition, Brain, Behavior], 9, 329-342.

- Varavikova, E. A. & Balachova, T. N. (2010). Strategies to implement physician training in FAS prevention as a part of preventive care in primary health settings: P120.Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 34(8) Sup 3:119A.

- Welsh, J. A., & Viana, A. G. (2012). Developmental outcomes of children adopted internationally. Adoption Quarterly, 15, 241-264.

Embracing ‘Translanguaging’ Practices: A Tutorial for SLPs

Please note that this post was originally published in the Summer 2016 NJSHA’s VOICES (available HERE).

If you have been keeping up with new developments in the field of bilingualism then you’ve probably heard the term “translanguaging,” increasingly mentioned at bilingual conferences across the nation. If you haven’t, ‘translanguaging’ is the “ability of multilingual speakers to shuttle between languages, treating the diverse languages that form their repertoire as an integrated system” (Canagarajah, 2011, p. 401). In other words, translanguaging allows bilinguals to make “flexible use their linguistic resources to make meaning of their lives and their complex worlds” (Garcia, 2011, pg. 1).

Wait a second, you might say! “Isn’t that a definition of ‘code-switching’?” And the answer is: “No!” The concept of ‘code-switching’ implies that bilinguals use two separate linguistic codes which do not overlap/reference each other. In contrast, ‘translanguaging’ assumes from the get-go that “bilinguals have one linguistic repertoire from which they select features strategically to communicate effectively” (Garcia, 2012, pg. 1). Bilinguals engage in translanguaging on an ongoing basis in their daily lives. They speak different languages to different individuals, find ‘Google’ translations of words and compare results from various online sites, listen to music in one language but watch TV in another, as well as watch TV announcers fluidly integrate several languages in their event narratives during news or in infomercials (Celic & Seltzer, 2011). For functional bilinguals, these practices are such integral part of their daily lives that they rarely realize just how much ‘translanguaging’ they actually do every day.

Wait a second, you might say! “Isn’t that a definition of ‘code-switching’?” And the answer is: “No!” The concept of ‘code-switching’ implies that bilinguals use two separate linguistic codes which do not overlap/reference each other. In contrast, ‘translanguaging’ assumes from the get-go that “bilinguals have one linguistic repertoire from which they select features strategically to communicate effectively” (Garcia, 2012, pg. 1). Bilinguals engage in translanguaging on an ongoing basis in their daily lives. They speak different languages to different individuals, find ‘Google’ translations of words and compare results from various online sites, listen to music in one language but watch TV in another, as well as watch TV announcers fluidly integrate several languages in their event narratives during news or in infomercials (Celic & Seltzer, 2011). For functional bilinguals, these practices are such integral part of their daily lives that they rarely realize just how much ‘translanguaging’ they actually do every day.

One of the most useful features of translanguaging (and there are many) is that it assists with further development of bilinguals’ metalinguistic awareness abilities by allowing them to compare language practices as well as explicitly notice language features. Consequently, not only do speech-language pathologists (SLPs) need to be aware of translanguaging when working with culturally diverse clients, they can actually assist their clients make greater linguistic gains by embracing translanguaging practices. Furthermore, one does not have to be a bilingual SLP to incorporate translanguaging practices in the therapy room. Monolingual SLPs can certainly do it as well, and with a great degree of success.

One of the most useful features of translanguaging (and there are many) is that it assists with further development of bilinguals’ metalinguistic awareness abilities by allowing them to compare language practices as well as explicitly notice language features. Consequently, not only do speech-language pathologists (SLPs) need to be aware of translanguaging when working with culturally diverse clients, they can actually assist their clients make greater linguistic gains by embracing translanguaging practices. Furthermore, one does not have to be a bilingual SLP to incorporate translanguaging practices in the therapy room. Monolingual SLPs can certainly do it as well, and with a great degree of success.

Here are some strategies of how this can be accomplished. Let us begin with bilingual SLPs who have the ability to do therapy in both languages. One great way to incorporate translanguaging in therapy is to alternate between English and the desired language (e.g., Spanish) throughout the session. Translanguaging strategies may include: using key vocabulary, grammar and syntax structures in both languages (side to side), alternating between English and Spanish websites when researching specific information (e.g., an animal habitats, etc.), asking students to take notes in both languages or combining two languages in one piece of writing. For younger preschool students, reading the same book, translated in another language is also a viable option as it increases their lexicon in both languages.

Here are some strategies of how this can be accomplished. Let us begin with bilingual SLPs who have the ability to do therapy in both languages. One great way to incorporate translanguaging in therapy is to alternate between English and the desired language (e.g., Spanish) throughout the session. Translanguaging strategies may include: using key vocabulary, grammar and syntax structures in both languages (side to side), alternating between English and Spanish websites when researching specific information (e.g., an animal habitats, etc.), asking students to take notes in both languages or combining two languages in one piece of writing. For younger preschool students, reading the same book, translated in another language is also a viable option as it increases their lexicon in both languages.

Those SLPs who treat ESL students with language disorders and collaborate with ESL teachers can design thematic intervention with a focus on particular topics of interest. For example, during the month of April there’s increased attention on the topic of ‘human impact on the environment.’ Students can read texts on this topic in English and then use the internet to look up websites containing the information in their birth language. They can also listen to a translation or a summary of the English book in their birth language. Finally, they can make comparisons of human impact on the environment between United States and their birth/heritage countries.

Those SLPs who treat ESL students with language disorders and collaborate with ESL teachers can design thematic intervention with a focus on particular topics of interest. For example, during the month of April there’s increased attention on the topic of ‘human impact on the environment.’ Students can read texts on this topic in English and then use the internet to look up websites containing the information in their birth language. They can also listen to a translation or a summary of the English book in their birth language. Finally, they can make comparisons of human impact on the environment between United States and their birth/heritage countries.

As we are treating culturally and linguistically diverse students it is important to use self-questions such as: “Can we connect a particular content-area topic to our students’ cultures?” or “Can we include different texts or resources in sessions which represent our students’ multicultural perspectives?” which can assist us in making best decisions in their care (Celic & Seltzer, 2011).

We can “Get to know our students” by displaying a world map in our therapy room/classroom and asking them to show us where they were born or came from (or where their family is from). We can label the map with our students’ names and photographs and provide them with the opportunity to discuss their culture and develop cultural connections. We can create a multilingual therapy room by using multilingual labels and word walls as well as sprinkling our English language therapy with words relevant to the students from their birth/heritage languages (e.g., songs and greetings, etc.).

We can “Get to know our students” by displaying a world map in our therapy room/classroom and asking them to show us where they were born or came from (or where their family is from). We can label the map with our students’ names and photographs and provide them with the opportunity to discuss their culture and develop cultural connections. We can create a multilingual therapy room by using multilingual labels and word walls as well as sprinkling our English language therapy with words relevant to the students from their birth/heritage languages (e.g., songs and greetings, etc.).

Monolingual SLPs who do not speak the child’s language or speak it very limitedly, can use multilingual books which contain words from other languages. To introduce just a few words in Spanish, books such as ‘Maňana Iguana’ by Ann Whitford Paul, ‘Count on Culebra’ by Ann Whitford Paul, ‘Abuela’ by Arthur Doros, or ‘Old man and his door’ by Gary Soto can be used. SLPs with greater proficiency in a particular language (e.g., Russian) they consider using dual bilingual books in sessions (e.g., ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’ by Kate Clynes, ‘Giant Turnip’ by Henriette Barkow. All of these books can be found on such websites as ‘Amazon’ (string search: children’s foreign language books), ‘Language Lizard’ or ‘Trilingual Mama’ (contains list of free online multilingual books).

It is also important to understand that many of our language impaired bilingual students have a very limited knowledge of the world beyond the “here and now.” Many upper elementary and middle school youngsters have difficulty naming world’s continents, and do not know the names and capitals of major countries. That is why it is also important to teach them general concepts of geography, discuss world’s counties and the people who live there, as well as introduce them to select multicultural holidays celebrated in United States and in other countries around the world.

All students benefit from translanguaging! It increases awareness of language diversity in monolingual students, validates use of home languages for bilingual students, as well as assists with teaching challenging academic content and development of English for emergent bilingual students. Translanguaging can take place in any classroom or therapy room with any group of children including those with primary language impairments or those speaking different languages from one another. The cognitive benefits of translanguaging are numerous because it allows students to use all of their languages as a resource for learning, reading, writing, and thinking in the classroom (Celic & Seltzer, 2011).

References:

- Canagarajah, A. S. (2011). Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal, 95, 401-417.

- García, O. (2011).Theorizing translanguaging for educators. In C. Celic & K. Seltzer, Translanguaging: A CUNY-NYSIEB guide for educators, 1-6.

Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Resources: