There are many fun yet highly educational therapy activities we can do with our preschool and school-aged clients in the fall. One of my personal favorites is bingo. Boggles World, an online ESL teacher resource actually has a number of ready-made materials, flashcards, and worksheets that can be adapted for speech-language therapy purposes. For example, their Fall and Halloween Bingo comes with both call out cards and a 3×3 and a 4×4 (as well as 3×3) card generator/boards. Clicking the refresh button will generate as many cards as you need, so the supply is endless! You can copy and paste the entire bingo board into a word document resize it and then print it out on reinforced paper or just laminate it. Continue reading Therapy Fun with Ready Made Fall and Halloween Bingo

There are many fun yet highly educational therapy activities we can do with our preschool and school-aged clients in the fall. One of my personal favorites is bingo. Boggles World, an online ESL teacher resource actually has a number of ready-made materials, flashcards, and worksheets that can be adapted for speech-language therapy purposes. For example, their Fall and Halloween Bingo comes with both call out cards and a 3×3 and a 4×4 (as well as 3×3) card generator/boards. Clicking the refresh button will generate as many cards as you need, so the supply is endless! You can copy and paste the entire bingo board into a word document resize it and then print it out on reinforced paper or just laminate it. Continue reading Therapy Fun with Ready Made Fall and Halloween Bingo

Category: Bilingual

Clinical Fellow (and Setting-Switching SLPs) Survival Guide in the Schools

It’s early August, and that means that the start of a new school year is just around the corner. It also means that many newly graduated clinical fellows (as well as SLPs switching their settings) will begin their exciting yet slightly terrifying new jobs working for various school systems around the country. Since I was recently interviewing clinical fellows myself in my setting (an outpatient school located in a psychiatric hospital, run by a university), I decided to write this post in order to assist new graduates, and setting-switching professionals by describing what knowledge and skills are desirable to possess when working in the schools. Continue reading Clinical Fellow (and Setting-Switching SLPs) Survival Guide in the Schools

It’s early August, and that means that the start of a new school year is just around the corner. It also means that many newly graduated clinical fellows (as well as SLPs switching their settings) will begin their exciting yet slightly terrifying new jobs working for various school systems around the country. Since I was recently interviewing clinical fellows myself in my setting (an outpatient school located in a psychiatric hospital, run by a university), I decided to write this post in order to assist new graduates, and setting-switching professionals by describing what knowledge and skills are desirable to possess when working in the schools. Continue reading Clinical Fellow (and Setting-Switching SLPs) Survival Guide in the Schools

Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Site Searching Tips

Over the years this blog has amassed many posts on a variety of topics pertaining to the assessment and treatment in speech-language pathology. With over 300 posts and over 130 search categories it’s no wonder that some of you have reached out to ask about effective ways of finding relevant information quickly. As such, in addition to the existing categories pertaining to specific topics (e.g., writing, social communication, etc.) I have created two specific categories which were asked about by numerous blog subscribers in recent emails. Continue reading Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Site Searching Tips

Over the years this blog has amassed many posts on a variety of topics pertaining to the assessment and treatment in speech-language pathology. With over 300 posts and over 130 search categories it’s no wonder that some of you have reached out to ask about effective ways of finding relevant information quickly. As such, in addition to the existing categories pertaining to specific topics (e.g., writing, social communication, etc.) I have created two specific categories which were asked about by numerous blog subscribers in recent emails. Continue reading Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Site Searching Tips

On the Disadvantages of Parents Ceasing to Speak the Birth Language with Bilingual Language Impaired Children

Despite significant advances in the fields of education and speech pathology, many harmful myths pertaining to multilingualism continue to persist. One particularly infuriating and patently incorrect recommendation to parents is the advice to stop speaking the birth language with their bilingual children with language disorders. Continue reading On the Disadvantages of Parents Ceasing to Speak the Birth Language with Bilingual Language Impaired Children

Despite significant advances in the fields of education and speech pathology, many harmful myths pertaining to multilingualism continue to persist. One particularly infuriating and patently incorrect recommendation to parents is the advice to stop speaking the birth language with their bilingual children with language disorders. Continue reading On the Disadvantages of Parents Ceasing to Speak the Birth Language with Bilingual Language Impaired Children

FREE Resources for Working with Russian Speaking Clients: Part III Introduction to “Dyslexia”

Given the rising interest in recent years in the role of SLPs in the treatment of reading disorders, today I wanted to share with parents and professionals several reputable FREE resources on the subject of “dyslexia” in Russian-speaking children.

Given the rising interest in recent years in the role of SLPs in the treatment of reading disorders, today I wanted to share with parents and professionals several reputable FREE resources on the subject of “dyslexia” in Russian-speaking children.

Now if you already knew that there was a dearth of resources on the topic of treating Russian speaking children with language disorders then it will not come as a complete shock to you that very few legitimate sources exist on this subject.

First up is the Report on the Russian Language for the World Dyslexia Forum 2010 by Dr. Grigorenko, the coauthor of the Dyslexia Debate. This 25-page report contains important information including Reading/Writing Acquisition of Russian in the Context of Typical and Atypical Development as well as on the state of Individuals with Dyslexia in Russia.

First up is the Report on the Russian Language for the World Dyslexia Forum 2010 by Dr. Grigorenko, the coauthor of the Dyslexia Debate. This 25-page report contains important information including Reading/Writing Acquisition of Russian in the Context of Typical and Atypical Development as well as on the state of Individuals with Dyslexia in Russia.

Next up is this delightful presentation entitled: “If John were Ivan: Would he fail in reading? Dyslexia & dysgraphia in Russian“. It is a veritable treasure trove of useful information on the topics of:

Next up is this delightful presentation entitled: “If John were Ivan: Would he fail in reading? Dyslexia & dysgraphia in Russian“. It is a veritable treasure trove of useful information on the topics of:

- The Russian language

- Literacy in Russia (Russian Federation)

- Dyslexia in Russia

- Definition

- Identification

- Policy

- Examples of good practice

- Teaching reading/language arts

• In regular schools

• In specialized settings - Encouraging children to learn

- Teaching reading/language arts

Now let us move on to the “The Role of Phonology, Morphology, and Orthography in English and Russian Spelling” which discusses that “phonology and morphology contribute more for spelling of English words while orthography and morphology contribute more to the spelling of Russian words“. It also provides clinicians with access to the stimuli from the orthographic awareness and spelling tests in both English and Russian, listed in its appendices.

Now let us move on to the “The Role of Phonology, Morphology, and Orthography in English and Russian Spelling” which discusses that “phonology and morphology contribute more for spelling of English words while orthography and morphology contribute more to the spelling of Russian words“. It also provides clinicians with access to the stimuli from the orthographic awareness and spelling tests in both English and Russian, listed in its appendices.

Finally, for parents and Russian speaking professionals, there’s an excellent article entitled, “Дислексия” in which Dr. Grigorenko comprehensively discusses the state of the field in Russian including information on its causes, rehabilitation, etc.

Related Helpful Resources:

- Анализ Нарративов У Детей С Недоразвитием Речи (Narrative Discourse Analysis in Children With Speech Underdevelopment)

- Narrative production weakness in Russian dyslexics: Linguistic or procedural limitations?

FREE Resources for Working with Russian Speaking Clients: Part II

A few years ago I wrote a blog post entitled “Working with Russian-speaking clients: implications for speech-language assessment” the aim of which was to provide some suggestions regarding assessment of bilingual Russian-American birth-school age population in order to assist SLPs with determining whether the assessed child presents with a language difference, insufficient language exposure, or a true language disorder.

Today I wanted to provide Russian speaking clinicians with a few FREE resources pertaining to the typical speech and language development of Russian speaking children 0-7 years of age.

Below materials include several FREE questionnaires regarding Russian language development (words and sentences) of children 0-3 years of age, a parent intake forms for Russian speaking clients, as well as a few relevant charts pertaining to the development of phonology, word formation, lexicon, morphology, syntax, and metalinguistics of children 0-7 years of age.

It is, however, important to note that due to the absence of research and standardized studies on this subject much of the below information still needs to be interpreted with significant caution.

Select Speech and Language Norms:

- Некоторые нормативы речевого развития детей от 18 до 36 месяцев (по материалам МакАртуровского опросника) (Number of words and sentence per age of Russian speakign children based on McArthur Bates)

- Речевой онтогенез: Развитие Речи Ребенка В Норме 0-7 years of age (based on the work of А.Н. Гвоздев) includes: Фонетика,Словообразование, Лексика, Морфолог-ия, Синтаксис, Метаязыковая деятельность (phonology, word formation, lexicon, morphology, syntax, and metalinguistics)

- Развитиe связной речи у детей 3-7 лет

a. Составление рассказа по серии сюжетных картинок

b. Пересказ текста

c. Составление описательного рассказа

Select Parent Questionnaires (McArthur Bates Adapted in Russian):

- Тест речевого и коммуникативного развития детей раннего возраста: слова и жесты (Words and Gestures)

- Тест речевого и коммуникативного развития детей раннего возраста: слова и предложения (Sentences)

- Анкета для родителей (Child Development Questionnaire for Parents)

Материал Для Родителей И Специалистов По Речевым

Нарушениям contains detailed information (27 pages) on Russian child development as well as common communication disrupting disorders

Stay tuned for more resources for Russian speaking SLPs coming shortly.

Related Resources:

- Working with Russian-speaking clients: implications for speech-language assessment

- Assessment of sound and syllable imitation in Russian speaking infants and toddlers

- Russian Articulation Screener

- Language Difference vs. Language Disorder: Assessment & Intervention Strategies for SLPs Working with Bilingual Children

- Impact of Cultural and Linguistic Variables On Speech-Language Services

Is it a Difference or a Disorder? Free Resources for SLPs Working with Bilingual and Multicultural Children

For bilingual and monolingual SLPs working with bilingual and multicultural children, the question of: “Is it a difference or a disorder?” arises on a daily basis as they attempt to navigate the myriad of difficulties they encounter in their attempts at appropriate diagnosis of speech, language, and literacy disorders.

For bilingual and monolingual SLPs working with bilingual and multicultural children, the question of: “Is it a difference or a disorder?” arises on a daily basis as they attempt to navigate the myriad of difficulties they encounter in their attempts at appropriate diagnosis of speech, language, and literacy disorders.

For that purpose, I’ve recently created a Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children. Its aim is to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) and Teachers in the decision-making process of how to appropriately identify bilingual/multicultural children who present with speech-language delay/deficits (vs. a language difference), for the purpose of initiating a formal speech-language-literacy evaluation. The goal is to ensure that educational professionals are appropriately identifying bilingual children for assessment and service provision due to legitimate speech language deficits/concerns, and are not over-identifying students because they speak multiple languages or because they come from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It is very important to understand that true language impairment in bilingual children will be evident in both languages from early childhood onwards, and thus will adversely affect the learning of both languages.

For that purpose, I’ve recently created a Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children. Its aim is to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) and Teachers in the decision-making process of how to appropriately identify bilingual/multicultural children who present with speech-language delay/deficits (vs. a language difference), for the purpose of initiating a formal speech-language-literacy evaluation. The goal is to ensure that educational professionals are appropriately identifying bilingual children for assessment and service provision due to legitimate speech language deficits/concerns, and are not over-identifying students because they speak multiple languages or because they come from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It is very important to understand that true language impairment in bilingual children will be evident in both languages from early childhood onwards, and thus will adversely affect the learning of both languages.

However, today the aim of today’s post is not on the above product but rather on the FREE free bilingual and multicultural resources available to SLPs online in their quest of differentiating between a language difference from a language disorder in bilingual and multicultural children.

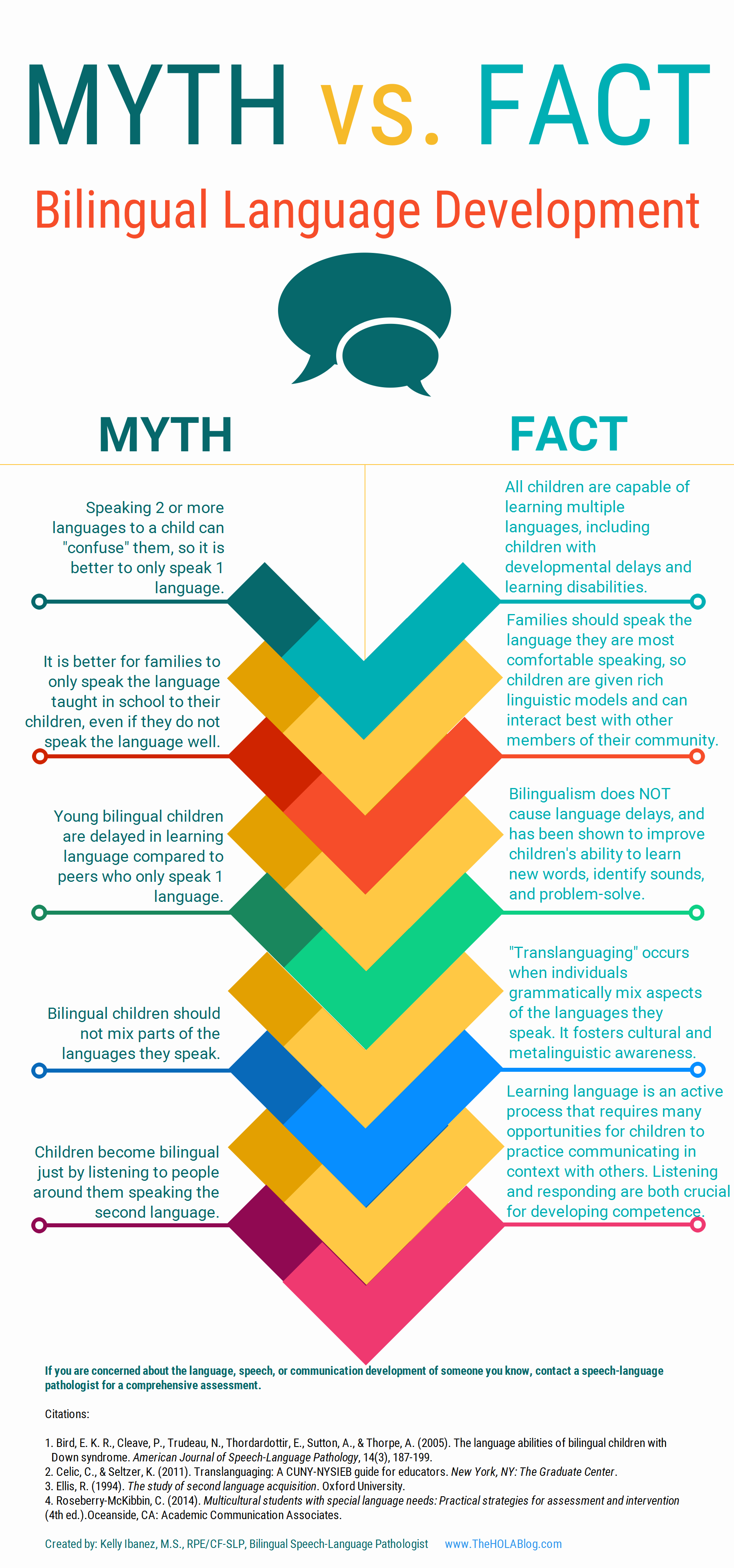

Let’s start with an excellent free infographic entitled from the Hola Blog “Myth vs. Fact: Bilingual Language Development” which was created by Kelly Ibanez, MS CCC-SLP to help dispel bilingual myths and encourage practices that promote multilingualism. Clinicians can download it and refer to it themselves, share it with other health and/or educational professionals as well as show it to parents of their clients.

Let’s start with an excellent free infographic entitled from the Hola Blog “Myth vs. Fact: Bilingual Language Development” which was created by Kelly Ibanez, MS CCC-SLP to help dispel bilingual myths and encourage practices that promote multilingualism. Clinicians can download it and refer to it themselves, share it with other health and/or educational professionals as well as show it to parents of their clients.

Let us now move on to the typical phonological development of English speaking children. After all, in order to compare other languages to English, SLPs need to be well versed in the acquisition of speech sounds in the English language. Children’s speech acquisition, developed by Sharynne McLeod, Ph.D., of Charles Sturt University, is one such resource. It contains a compilation of data on typical speech development for English speaking children, which is organized according to children’s ages to reflect a typical developmental sequence.

Next up, is a great archive which contains phonetic inventories of the various language spoken around the world for contrastive analysis purposes. The same website also contains a speech accent archive. Native and non-native speakers of English were recorded reading the same English paragraph for teaching and research purposes. It is meant to be used by professionals who are interested in comparing the accents of different English speakers.

Next up, is a great archive which contains phonetic inventories of the various language spoken around the world for contrastive analysis purposes. The same website also contains a speech accent archive. Native and non-native speakers of English were recorded reading the same English paragraph for teaching and research purposes. It is meant to be used by professionals who are interested in comparing the accents of different English speakers.

![]() Now let’s talk about one of my favorite websites, MULTILINGUAL CHILDREN’S SPEECH, also developed by Dr. Mcleod of Charles Stuart University. It contains an AMAZING plethora of resources on bilingual speech development and assessment. To illustrate, its Speech Acquisition Data includes A list of over 200 speech acquisition studies. It also contains a HUGE archive on Speech Assessments in NUMEROUS LANGUAGES as well as select assessment reviews. Finally, the website also lists in detail how aspects of speech (e.g., consonants, vowels, syllables, tones) differ between languages.

Now let’s talk about one of my favorite websites, MULTILINGUAL CHILDREN’S SPEECH, also developed by Dr. Mcleod of Charles Stuart University. It contains an AMAZING plethora of resources on bilingual speech development and assessment. To illustrate, its Speech Acquisition Data includes A list of over 200 speech acquisition studies. It also contains a HUGE archive on Speech Assessments in NUMEROUS LANGUAGES as well as select assessment reviews. Finally, the website also lists in detail how aspects of speech (e.g., consonants, vowels, syllables, tones) differ between languages.

The Leader’s Project Website is another highly informative source of FREE information on bilingual assessments, intervention, and FREE CEUS.

Now, I’d like to list some resources regarding language transfer errors.

This chart from Cengage Learning contains a nice, concise Language Guide to Transfer Errors. While it is aimed at multilingual/ESL writers, the information contained on the site is highly applicable to multilingual speakers as well.

You can also find a bonus transfer chart HERE. It contains information on specific structures such as articles, nouns, verbs, pronouns, adverbs, adjectives, word order, questions, commands, and negatives on pages 1-6 and phonemes on pages 7-8.

A final bonus chart entitled: Teacher’s Resource Guide of Language Transfer Issues for English Language Learners containing information on grammar and phonics for 10 different languages can be found HERE.

Similarly, this 16-page handout: Language Transfers: The Interaction Between English and Students’ Primary Languages also contains information on phonics and grammar transfers for Spanish, Cantonese, Vietnamese, Hmong Korean, and Khmer languages.

For SLPs working with Russian-speaking children the following links pertinent to assessment, intervention and language transference may be helpful:

For SLPs working with Russian-speaking children the following links pertinent to assessment, intervention and language transference may be helpful:

- Working with Russian-speaking clients: implications for speech-language assessment

- Strategies in the acquisition of segments and syllables in Russian-speaking children

- Language Development of Bilingual Russian/ English Speaking Children Living in the United States: A Review of the Literature

- The acquisition of syllable structure by Russian-speaking children with SLI

To determine information about the children’s language development and language environment, in both their first and second language, visit the CHESL Centre website for The Alberta Language Development Questionnaire and The Alberta Language Environment Questionnaire

There you have it! FREE bilingual/multicultural SLP resources compiled for you conveniently in one place. And since there are much more FREE GEMS online, I’d love it if you guys contributed to and expanded this modest list by posting links and title descriptions in the comments section below for others to benefit from!

Together we can deliver the most up to date evidence-based assessment and intervention to bilingual and multicultural students that we serve! Click HERE to check out the FREE Resources in the SLPs for Evidence-Based Practice Group

Helpful Bilingual Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

- Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children

- Multicultural Assessment Bundle

- Best Practices in Bilingual Literacy Assessments and Interventions

- Dynamic Assessment of Bilingual and Multicultural Learners in Speech-Language Pathology

- Practical Strategies for Monolingual SLPs Assessing and Treating Bilingual Children

- Language Difference vs. Language Disorder: Assessment & Intervention Strategies for SLPs Working with Bilingual Children

- Impact of Cultural and Linguistic Variables On Speech-Language Services

- Assessment of sound and syllable imitation in Russian-speaking infants and toddlers

- Russian Articulation Screener

- Creating Translanguaging Classrooms and Therapy Rooms

Embracing ‘Translanguaging’ Practices: A Tutorial for SLPs

Please note that this post was originally published in the Summer 2016 NJSHA’s VOICES (available HERE).

If you have been keeping up with new developments in the field of bilingualism then you’ve probably heard the term “translanguaging,” increasingly mentioned at bilingual conferences across the nation. If you haven’t, ‘translanguaging’ is the “ability of multilingual speakers to shuttle between languages, treating the diverse languages that form their repertoire as an integrated system” (Canagarajah, 2011, p. 401). In other words, translanguaging allows bilinguals to make “flexible use their linguistic resources to make meaning of their lives and their complex worlds” (Garcia, 2011, pg. 1).

Wait a second, you might say! “Isn’t that a definition of ‘code-switching’?” And the answer is: “No!” The concept of ‘code-switching’ implies that bilinguals use two separate linguistic codes which do not overlap/reference each other. In contrast, ‘translanguaging’ assumes from the get-go that “bilinguals have one linguistic repertoire from which they select features strategically to communicate effectively” (Garcia, 2012, pg. 1). Bilinguals engage in translanguaging on an ongoing basis in their daily lives. They speak different languages to different individuals, find ‘Google’ translations of words and compare results from various online sites, listen to music in one language but watch TV in another, as well as watch TV announcers fluidly integrate several languages in their event narratives during news or in infomercials (Celic & Seltzer, 2011). For functional bilinguals, these practices are such integral part of their daily lives that they rarely realize just how much ‘translanguaging’ they actually do every day.

Wait a second, you might say! “Isn’t that a definition of ‘code-switching’?” And the answer is: “No!” The concept of ‘code-switching’ implies that bilinguals use two separate linguistic codes which do not overlap/reference each other. In contrast, ‘translanguaging’ assumes from the get-go that “bilinguals have one linguistic repertoire from which they select features strategically to communicate effectively” (Garcia, 2012, pg. 1). Bilinguals engage in translanguaging on an ongoing basis in their daily lives. They speak different languages to different individuals, find ‘Google’ translations of words and compare results from various online sites, listen to music in one language but watch TV in another, as well as watch TV announcers fluidly integrate several languages in their event narratives during news or in infomercials (Celic & Seltzer, 2011). For functional bilinguals, these practices are such integral part of their daily lives that they rarely realize just how much ‘translanguaging’ they actually do every day.

One of the most useful features of translanguaging (and there are many) is that it assists with further development of bilinguals’ metalinguistic awareness abilities by allowing them to compare language practices as well as explicitly notice language features. Consequently, not only do speech-language pathologists (SLPs) need to be aware of translanguaging when working with culturally diverse clients, they can actually assist their clients make greater linguistic gains by embracing translanguaging practices. Furthermore, one does not have to be a bilingual SLP to incorporate translanguaging practices in the therapy room. Monolingual SLPs can certainly do it as well, and with a great degree of success.

One of the most useful features of translanguaging (and there are many) is that it assists with further development of bilinguals’ metalinguistic awareness abilities by allowing them to compare language practices as well as explicitly notice language features. Consequently, not only do speech-language pathologists (SLPs) need to be aware of translanguaging when working with culturally diverse clients, they can actually assist their clients make greater linguistic gains by embracing translanguaging practices. Furthermore, one does not have to be a bilingual SLP to incorporate translanguaging practices in the therapy room. Monolingual SLPs can certainly do it as well, and with a great degree of success.

Here are some strategies of how this can be accomplished. Let us begin with bilingual SLPs who have the ability to do therapy in both languages. One great way to incorporate translanguaging in therapy is to alternate between English and the desired language (e.g., Spanish) throughout the session. Translanguaging strategies may include: using key vocabulary, grammar and syntax structures in both languages (side to side), alternating between English and Spanish websites when researching specific information (e.g., an animal habitats, etc.), asking students to take notes in both languages or combining two languages in one piece of writing. For younger preschool students, reading the same book, translated in another language is also a viable option as it increases their lexicon in both languages.

Here are some strategies of how this can be accomplished. Let us begin with bilingual SLPs who have the ability to do therapy in both languages. One great way to incorporate translanguaging in therapy is to alternate between English and the desired language (e.g., Spanish) throughout the session. Translanguaging strategies may include: using key vocabulary, grammar and syntax structures in both languages (side to side), alternating between English and Spanish websites when researching specific information (e.g., an animal habitats, etc.), asking students to take notes in both languages or combining two languages in one piece of writing. For younger preschool students, reading the same book, translated in another language is also a viable option as it increases their lexicon in both languages.

Those SLPs who treat ESL students with language disorders and collaborate with ESL teachers can design thematic intervention with a focus on particular topics of interest. For example, during the month of April there’s increased attention on the topic of ‘human impact on the environment.’ Students can read texts on this topic in English and then use the internet to look up websites containing the information in their birth language. They can also listen to a translation or a summary of the English book in their birth language. Finally, they can make comparisons of human impact on the environment between United States and their birth/heritage countries.

Those SLPs who treat ESL students with language disorders and collaborate with ESL teachers can design thematic intervention with a focus on particular topics of interest. For example, during the month of April there’s increased attention on the topic of ‘human impact on the environment.’ Students can read texts on this topic in English and then use the internet to look up websites containing the information in their birth language. They can also listen to a translation or a summary of the English book in their birth language. Finally, they can make comparisons of human impact on the environment between United States and their birth/heritage countries.

As we are treating culturally and linguistically diverse students it is important to use self-questions such as: “Can we connect a particular content-area topic to our students’ cultures?” or “Can we include different texts or resources in sessions which represent our students’ multicultural perspectives?” which can assist us in making best decisions in their care (Celic & Seltzer, 2011).

We can “Get to know our students” by displaying a world map in our therapy room/classroom and asking them to show us where they were born or came from (or where their family is from). We can label the map with our students’ names and photographs and provide them with the opportunity to discuss their culture and develop cultural connections. We can create a multilingual therapy room by using multilingual labels and word walls as well as sprinkling our English language therapy with words relevant to the students from their birth/heritage languages (e.g., songs and greetings, etc.).

We can “Get to know our students” by displaying a world map in our therapy room/classroom and asking them to show us where they were born or came from (or where their family is from). We can label the map with our students’ names and photographs and provide them with the opportunity to discuss their culture and develop cultural connections. We can create a multilingual therapy room by using multilingual labels and word walls as well as sprinkling our English language therapy with words relevant to the students from their birth/heritage languages (e.g., songs and greetings, etc.).

Monolingual SLPs who do not speak the child’s language or speak it very limitedly, can use multilingual books which contain words from other languages. To introduce just a few words in Spanish, books such as ‘Maňana Iguana’ by Ann Whitford Paul, ‘Count on Culebra’ by Ann Whitford Paul, ‘Abuela’ by Arthur Doros, or ‘Old man and his door’ by Gary Soto can be used. SLPs with greater proficiency in a particular language (e.g., Russian) they consider using dual bilingual books in sessions (e.g., ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’ by Kate Clynes, ‘Giant Turnip’ by Henriette Barkow. All of these books can be found on such websites as ‘Amazon’ (string search: children’s foreign language books), ‘Language Lizard’ or ‘Trilingual Mama’ (contains list of free online multilingual books).

It is also important to understand that many of our language impaired bilingual students have a very limited knowledge of the world beyond the “here and now.” Many upper elementary and middle school youngsters have difficulty naming world’s continents, and do not know the names and capitals of major countries. That is why it is also important to teach them general concepts of geography, discuss world’s counties and the people who live there, as well as introduce them to select multicultural holidays celebrated in United States and in other countries around the world.

All students benefit from translanguaging! It increases awareness of language diversity in monolingual students, validates use of home languages for bilingual students, as well as assists with teaching challenging academic content and development of English for emergent bilingual students. Translanguaging can take place in any classroom or therapy room with any group of children including those with primary language impairments or those speaking different languages from one another. The cognitive benefits of translanguaging are numerous because it allows students to use all of their languages as a resource for learning, reading, writing, and thinking in the classroom (Celic & Seltzer, 2011).

References:

- Canagarajah, A. S. (2011). Codemeshing in academic writing: Identifying teachable strategies of translanguaging. The Modern Language Journal, 95, 401-417.

- García, O. (2011).Theorizing translanguaging for educators. In C. Celic & K. Seltzer, Translanguaging: A CUNY-NYSIEB guide for educators, 1-6.

Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

Have you Worked on Morphological Awareness Lately?

Last year an esteemed colleague, Dr. Roseberry-McKibbin posed this question in our Bilingual SLPs Facebook Group: “Is anyone working on morphological awareness in therapy with ELLs (English Language Learners) with language disorders?”

Last year an esteemed colleague, Dr. Roseberry-McKibbin posed this question in our Bilingual SLPs Facebook Group: “Is anyone working on morphological awareness in therapy with ELLs (English Language Learners) with language disorders?”

Her question got me thinking: “How much time do I spend on treating morphological awareness in therapy with monolingual and bilingual language disordered clients?” The answer did not make me happy!

So what is morphological awareness and why is it important to address when treating monolingual and bilingual language impaired students?

Morphemes are the smallest units of language that carry meaning. They can be free (stand alone words such as ‘fair’, ‘toy’, or ‘pretty’) or bound (containing prefixes and suffixes that change word meanings – ‘unfair’ or ‘prettier’).

Morphological awareness refers to a ‘‘conscious awareness of the morphemic structure of words and the ability to reflect on and manipulate that structure’’ (Carlisle, 1995, p. 194). Also referred to as “the study of word structure” (Carlisle, 2004), it is an ability to recognize, understand, and use affixes or word parts (prefixes, suffixes, etc) that “carry significance” when speaking as well as during reading tasks. It is a hugely important skill for building vocabulary, reading fluency and comprehension as well as spelling (Apel & Lawrence, 2011; Carlisle, 2000; Binder & Borecki, 2007; Green, 2009).

So why is teaching morphological awareness important? Let’s take a look at some research.

Goodwin and Ahn (2010) found morphological awareness instruction to be particularly effective for children with speech, language, and/or literacy deficits. After reviewing 22 studies Bowers et al. (2010) found the most lasting effect of morphological instruction was on readers in early elementary school who struggled with literacy.

Morphological awareness instruction mediates and facilitates vocabulary acquisition leading to improved reading comprehension abilities (Bowers & Kirby, 2010; Carlisle, 2003, 2010; Guo, Roehrig, & Williams, 2011; Tong, Deacon, Kirby, Cain, & Parilla, 2011).

Unfortunately as important morphological instruction is for vocabulary building, reading fluency, reading comprehension, and spelling, it is often overlooked during the school years until it’s way too late. For example, traditionally morphological instruction only beings in late middle school or high school but research actually found that in order to be effective one should actually begin teaching it as early as first grade (Apel & Lawrence, 2011).

So now that we know that we need to target morphological instruction very early in children with language deficits, let’s talk a little bit regarding how morphological awareness can be assessed in language impaired learners.

When it comes to standardized testing, both the Test of Language Development: Intermediate – Fourth Edition (TOLD-I:4) and the Test of Adolescent and Adult Language–Fourth Edition (TOAL-4) have subtests which assess morphology as well as word derivations. However if you do not own either of these tests you can easily create non-standardized tasks to assess morphological awareness.

Apel, Diehm, & Apel (2013) recommend multiple measures which include: phonological awareness tasks, word level reading tasks, as well as reading comprehension tasks.

Below are direct examples of tasks from their study:

One can test morphological awareness via production or decomposition tasks. In a production task a student is asked to supply a missing word, given the root morpheme (e.g., ‘‘Sing. He is a great _____.’’ Correct response: singer). A decomposition task asks the student to identify the correct root of a given derivation or inflection. (e.g., ‘‘Walker. How slow can she _____?’’ Correct response: walk).

Another way to test morphological awareness is through completing analogy tasks since it involves both decomposition and production components (provide a missing word based on the presented pattern—crawl: crawled:: fly: ______ (flew).

Still another way to test morphological awareness with older students is through deconstruction tasks: Tell me what ____ word means? How do you know? (The student must explain the meaning of individual morphemes).

Finding the affix: Does the word ______ have smaller parts?

So what are the components of effective morphological instruction you might ask?

Below is an example of a ‘Morphological Awareness Intervention With Kindergarteners and First and Second Grade Students From Low SES Homes’ performed by Apel & Diehm, 2013:

Here are more ways in which this can be accomplished with older children:

- Find the root word in a longer word

- Fix the affix (an additional element placed at the beginning or end of a root, stem, or word, or in the body of a word, to modify its meaning)

- Affixes at the beginning of words are called “prefixes”

- Affixes at the end of words are called “suffixes

- Word sorts to recognize word families based on morphology or orthography

- Explicit instruction of syllable types to recognize orthographical patterns

- Word manipulation through blending and segmenting morphemes to further solidify patterns

Now that you know about the importance of morphological awareness, will you be incorporating it into your speech language sessions? I’d love to know!

Until then, Happy Speeching!

References:

- Apel, K., & Diehm, E. (2013). Morphological awareness intervention with kindergarteners and first and second grade students from low SES homes: A small efficacy study. Journal of Learning Disabilities.

- Apel, K., & Lawrence, J. (2011). Contributions of morphological awareness skills to word-level reading and spelling in first-grade children with and without speech sound disorder. Journal of Speech, Language & Hearing Research, 54, 1312–1327.

- Apel, K., Brimo, D., Diehm, E., & Apel, L. (2013). Morphological awareness intervention with kindergarteners and first and second grade students from low SES homes: A feasibility study. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 44, 161-173.

- Binder, K. & Borecki, C. (2007). The use of phonological, orthographic, and contextualinformation during reading: a comparison of adults who are learning to read and skilled adult readers. Reading and Writing, 21, 843-858.

- Bowers, P.N., Kirby, J.R., Deacon, H.S. (2010). The effects of morphological instruction on literacy skills: A systematic review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 80, 144-179.

- Carlisle, J. F. (1995). Morphological awareness and early reading achievement. In L. B. Feldman (Ed.), Morphological aspects of language processing (pp. 189–209). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Carlisle, J. F. (2000). Awareness of the structure and meaning of morphologically complex words: Impact on reading. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal,12,169-190.

- Carlisle, J. F. (2004). Morphological processes that influence learning to read. In C. A. Stone, E. R. Silliman, B. J. Ehren, & K. Apel (Eds.), Handbook of language and literacy. NY: Guilford Press.

- Carlisle, J. F. (2010). An integrative review of the effects of instruction in morphological awareness on literacy achievement. Reading Research Quarterly, 45(4), 464-487.

- Goodwin, A.P. & Ahn, S. (2010). Annals of Dyslexia, 60, 183-208.

- Green, L. (2009). Morphology and literacy: Getting our heads in the game. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in the schools, 40, 283-285.

- Green, L., & Wolter, J.A. (2011, November). Morphological Awareness Intervention: Techniques for Promoting Language and Literacy Success. A symposium presentation at the annual American Speech Language Hearing Association, San Diego, CA.

- Guo, Y., Roehrig, A. D., & Williams, R. S. (2011). The relation of morphological awareness and syntactic awareness to adults’ reading comprehension: Is vocabulary knowledge a mediating variable? Journal of Literacy Research, 43, 159-183.

- Tong, X., Deacon, S. H., Kirby, J. R., Cain, K., & Parrila, R. (2011). Morphological awareness: A key to understanding poor reading comprehension in English. Journal of Educational Psychology, 103 (3), 523-534.

Assessing and Treating Bilinguals Who Stutter: Facts for Bilingual and Monolingual SLPs

Introduction: When it comes to bilingual children who stutter there is still considerable amount of misinformation regarding the best recommendations on assessment and treatment. The aim of this article is to review best practices in assessment and treatment of bilingual children who stutter, to shed some light on this important yet highly misunderstood area in speech-language pathology.

Types of Bilingualism: Young bilingual children can be broadly divided into two categories: those who are learning several languages simultaneously from birth (simultaneous bilingual), and those who begin to learn a second language after two years of age (sequential bilingual) (De Houwer, 2009b). The language milestones for simultaneous bilinguals may be somewhat uneven but they are not that much different from those of monolingual children (De Houwer, 2009a). Namely, first words emerge between 8 and 15 months and early phrase production occurs around +/-20 months of age, with sentence production following thereafter (De Houwer, 2009b). In contrast, sequential bilinguals undergo a number of stages during which they acquire abilities in the second language, which include preproduction, early production, as well as intermediate and advanced proficiency in the second language.

Stuttering and Monolingual Children: With respect to stuttering in the monolingual children we know that there are certain risk factors associated with stuttering. These include family history (family members who stutter), age of onset (children who begin stuttering before the age of three have a greater likelihood of outgrowing stuttering), time since onset (depending on how long the child have been stuttering certain children may outgrow it), gender (research has shown that girls are more likely to outgrow stuttering than boys), presence of other speech/language factors (poor speech intelligibility, advance language skills etc.) (Stuttering Foundation: Risk Factors). We also know that the symptoms of stuttering manifest via sound, syllable and word repetitions, sound prolongations as well as sound and word blocks. In addition to overt stuttering characteristics there could also be secondary characteristics including gaze avoidance, word substitutions, anxiety about speaking, muscle tension in the face, jaw and neck, as well as fist clenching, just to name a few.

Stuttering and Bilingual Children: So what do we currently know regarding the manifestations of stuttering in bilingual children? Here is some information based on existing research. While some researchers believe that stuttering is more common in bilingual versus monolingual individuals, currently there is no data which supports such a hypothesis. The distribution and severity of stuttering tend to differ from language to language and one language is typically affected more than the other (Van Borsel, Maes & Foulon, 2001). Lim and colleagues (2008) found that language dominance influences the severity but not the types of stuttering behaviors. They also found that bilingual stutterers exhibit different stuttering characteristics in both languages such as displaying stuttering on content words in L1 and function words in L2 (less-developed language system). According to Watson & Kayser (1994) key features of ‘true’ stuttering include the presence of stuttering in both languages with accompanying self-awareness as well as secondary behaviors. This is important to understand giving the fact that bilingual children in the process of learning another language may present with pseudo-stuttering characteristics related to word retrieval rather than true stuttering.

Assessment of Bilingual Stutterers: Now let’s talk about aspects of the assessment. Typically assessment should begin with the taking of detailed background history regarding stuttering risk factors, the extent of the child’s exposure and proficiency in each language, age of stuttering onset, the extent of stuttering in each language, as well as presence of any other concomitant concerns regarding the child’s speech and language (e.g., suspicion of language/articulation deficits etc.) Shenker (2013) also recommends the parental use of perceptual rating scales to assess child’s proficiency in each language.

Assessment procedures, especially those for newly referred children (vs. children whose speech and language abilities were previously assessed), should include comprehensive assessments of speech and language in addition to assessment of stuttering in order to rule out any hidden concomitant deficits. It is also important to obtain conversational and narrative samples in each language as well as reading samples when applicable. When analyzing the samples it is very important to understand and make allowance for typical disfluencies (especially when it comes to preschool children) as well as understand the difference between true stuttering and word retrieval deficits (which pertain to linguistic difficulties), which can manifest as fillers, word phrase repetitions, as well as conversational pauses (German, 2005).

When analyzing the child’s conversational speech for dysfluencies it may be helpful to gradually increase linguistic complexity in order to determine at which level (e.g., word, phrase, etc.) dysfluencies take place (Schenker, 2013). To calculate frequency and duration of disfluencies, word-based (vs. syllable-based) counts of stuttering frequency will be more accurate across languages (Bernstein Ratner, 2004).

Finally during the assessment it is also very important to determine the family’s cultural beliefs toward stuttering since stuttering perceptions vary greatly amongst different cultures (Tellis & Tellis, 2003) and may not always be positive. For example, Waheed-Kahn (1998) found that Middle Eastern parents attempted to deal with their children’s stuttering in the following ways: prayed for change, asked them to “speak properly”, completed their sentences, changed their setting by sending them to live with a relative as well as asked them not to talk in public. Gauging familial beliefs toward stuttering will allow clinicians to: understand parental involvement and acceptance of therapy services, select best treatment models for particular clients as well as gain knowledge of how cultural attitudes may impact treatment outcomes (Schenker, 2013).

Image courtesy of mnsu.edu

Treatment of Bilingual Stutterers: With respect to stuttering treatment delivery for bilingual children, research has found that treatment in one language results in spontaneous improvement in fluency in the untreated language (Rousseau, Packman, & Onslow, 2005). This is helpful for monolingual SLPs who often do not have the option of treating clients in their birth language.

For young preschool children both direct and indirect therapy approaches may be utilized.

For example, the Palin (PCI) approach for children 2-7 years of age uses play-based sessions, video feedback, and facilitated discussions to help parents support and increase their child’s fluency. Its primary focus is to modify parent–child interactions via a facilitative rather than an instructive approach by developing and reinforcing parents’ expertise via use of video feedback to set own targets and reinforce progress. In contrast, the Lidcombe Program for children 2-7 years of age is a behavioral treatment with a focus on stuttering elimination. It is administered by the parents under the supervision of an SLP, who teaches the parents how to control the child’s stuttering with verbal response contingent stimulation (Onslow & Millard, 2012). While the Palin PCI approach still requires further research to determine its use with bilingual children, the Lidcombe Program has been trialed in a number of studies with bilingual children and was found to be effective in both languages (Schenker, 2013).

For bilingual school-age children with persistent stuttering, it is important to focus on stuttering management vs. stuttering elimination (Reardon-Reeves & Yaruss, 2013). Here we are looking to reduce frequency and severity of disfluencies, teach the children to successfully manage stuttering moments, as well as work on the student’s emotional attitude toward stuttering. Use of support groups for children who stutter (e.g., “FRIENDS”: http://www.friendswhostutter.org/), may also be recommended.

Depending on the student’s preferences, desires, and needs, the approaches may involve a combination of fluency shaping and stuttering modification techniques. Fluency shaping intervention focuses on increasing fluent speech through teaching methods that reduce speaking rate such as easy onsets, loose contacts, changing breathing, prolonging sounds or words, pausing, etc. The goal of fluency shaping is to “encourage spontaneous fluency where possible and controlled fluency when it is not” (Ramig & Dodge, 2004). In contrast stuttering modification therapy focuses on modifying the severity of stuttering moments as well as on reduction of fear, anxiety and avoidance behaviors associated with stuttering. Stuttering modification techniques are aimed at assisting the client “to confront the stuttering moment through implementation of pre-block, in-block, and/or post-block corrections, as well as through a change in how they perceive the stuttering experience” (Ramig & Dodge, 2004). While studies on these treatment methods are still very limited it is important to note that each technique as well as a combination of both techniques have been trialed and found successful with bilingual and even trilingual speakers (Conture & Curlee, 2007; Howell & Van Borsel, 2011).

Finally, it is very important for clinicians to account for cultural differences during treatment. This can be accomplished by carefully selecting culturally appropriate stimuli, preparing instructions which account for the parents’ language and culture, attempting to provide audio/video examples in the child’s birth language, as well as finding/creating opportunities for practicing fluency in culturally-relevant contexts and activities (Schenker, 2013).

Conclusion: Presently, no evidence has been found that bilingualism causes stuttering. Furthermore, treatment outcomes for bilingual children appear to be comparable to those of monolingual children. Bilingual SLPs encountering bilingual children who stutter are encouraged to provide stuttering treatment in the language the child is most proficient in. Monolingual SLPs encountering bilingual children are encouraged to provide stuttering treatment in English with the expectation that the treatment will carry over into the child’s birth language. All clinicians are encouraged to involve the children’s families in the stuttering treatment as well as utilize methods and interventions that are in agreement with the family’s cultural beliefs and values, in order to create optimum treatment outcomes for bilingual children who stutter.

References:

- Bernstein Ratner, N. (2004). Fluency and stuttering in bilingual children. In B. Goldstein (ed.). Language Development: a focus on the Spanish-English speaker. Baltimore, MD: Brookes. (287-310).

- Conture, E. G., & Curlee, R. F. (2007). Stuttering and related disorders of fl uency. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers.

- De Houwer, A. (2009a). Bilingual first language acquisition. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- De Houwer, A. (2009b). Assessing lexical development in bilingual first language acquisition: What can we learn from monolingual norms? In M. Cruz-Ferreira (Ed.), Multilingual norms (pp. 279-322). Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- German, D.J. (2005) Word-Finding Intervention Program, Second Edition (WFIP-2)Austin Texas: Pro.Ed

- Howell, P & Van Borsel, , (2011). Multicultural Aspects of Fluency Disorders, Multilingual Matters, Bristol, UK.

- Lim, V. P. C., Rickard Liow, S. J., Lincoln, M., Chan, Y. H., & Onslow, M. (2008). Determining language dominance in English–Mandarin bilinguals: Development of a selfreport classification tool for clinical use. Applied Psycholinguistics, 29, 389–412.

- Onslow M, Millard S. (2012). Palin Parent Child Interaction and the Lidcombe Program: Clarifying some issues. Journal of Fluency Disorders37(1 ):1-8.

- Tellis, G. & Tellis, C. (2003). Multicultural issues in school settings. Seminars in Speech and Language, 24, 21-26.

- Ramig, P. R., & Dodge, D. (2004, September 08). Fluency shaping intervention: Helpful, but why it is important to know more. Retrieved from http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/isad7/papers/ramig7.html

- Reardon-Reeves, N., & Yaruss, J.S. (2013). School-age Stuttering Therapy: A Practical Guide. McKinney, TX: Stuttering Therapy Resources, Inc.

- Rousseau, I., Packman, A., & Onslow, M. (2005, June). A trial of the Lidcombe Program with school age stuttering children. Paper presented at the Speech Pathology National Conference, Canberra, Australia.

- Shenker, R. C. (2013). Bilingual myth-busters series. When young children who stutter are also bilingual: Some thoughts about assessment and treatment. Perspectives on Communication Disorders and Sciences in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CLD) Populations, 20(1), 15-23.

- Stuttering Foundation website: Stuttering Risk Factors http://www.stutteringhelp.org/risk-factors

- Van Borsel, J. Maes, E., & Foulon, S. (2001). Stuttering and bilingualism: A review. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 26, 179-205.

- Waheed-Kahn, N. (1998). Fluency therapy with multilingual clients. In Healey, E. C. & Peters, H. F. M. (Eds.),Proceedings of the Second World Congress on Fluency Disorders, San Francisco, August 18. 22(pp. 195–199). Nijmegen, The Netherlands: Nijmegen University Press.

- Watson, J., & Kayser, H. (1994). Assessment of bilingual/bicultural adults who stutter. Seminars in Speech and Language, 15, 149-163.