In my previous posts, I’ve shared my thoughts about picture books being an excellent source of materials for assessment and treatment purposes. They can serve as narrative elicitation aids for children of various ages and intellectual abilities, ranging from pre-K through fourth grade. They are also incredibly effective treatment aids for addressing a variety of speech, language, and literacy goals that extend far beyond narrative production. Continue reading Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Karma Wilson’s “Bear” Books

In my previous posts, I’ve shared my thoughts about picture books being an excellent source of materials for assessment and treatment purposes. They can serve as narrative elicitation aids for children of various ages and intellectual abilities, ranging from pre-K through fourth grade. They are also incredibly effective treatment aids for addressing a variety of speech, language, and literacy goals that extend far beyond narrative production. Continue reading Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Karma Wilson’s “Bear” Books

Category: Articulation

Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Helen Lester’s Picture Books

Picture books are absolutely wonderful for both assessment and treatment purposes! They are terrific as narrative elicitation aids for children of various ages, ranging from pre-K through fourth grade. They are amazing treatment aids for addressing a variety of speech, language, and literacy goals that extend far beyond narrative production. Continue reading Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Helen Lester’s Picture Books

Picture books are absolutely wonderful for both assessment and treatment purposes! They are terrific as narrative elicitation aids for children of various ages, ranging from pre-K through fourth grade. They are amazing treatment aids for addressing a variety of speech, language, and literacy goals that extend far beyond narrative production. Continue reading Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Helen Lester’s Picture Books

Early Intervention Evaluations PART II: Assessing Suspected Motor Speech Disorders in Children Under 3

In my previous post on this topic, I brought up concerns regarding the paucity of useful information in EI SLP reports for children under 3 years of age and made some constructive suggestions of how that could be rectified. In 2013, I had written about another significant concern, which involved neurodevelopmental pediatricians (rather than SLPs), diagnosing Childhood Apraxia of Speech (CAS), without the adequate level of training and knowledge regarding motor speech disorders. Today, I wanted to combine both topics and delve deeper into another area of EI SLP evaluations, namely, assessments of toddlers with suspected motor speech disorders.

Firstly, it is important to note that CAS is disturbingly overdiagnosed. A cursory review of both parent and professional social media forums quickly reveals that this diagnosis is doled out like candy by both SLPs and medical professionals alike, often without much training and knowledge regarding the disorder in question. The child is under 3, has a limited verbal output coupled with a number of phonological processes, and the next thing you know, s/he is labeled as having Childhood Apraxia of Speech (CAS). But is this diagnosis truly that straightforward?

Let us begin with the fact that all reputable organizations involved in the dissemination of information on the topic of CAS (e.g., ASHA, CASANA, etc.), strongly discourage the diagnosis of CAS in children under three years of age with limited verbal output, and limited time spent in EBP therapy specifically targeting the remediation of motor speech disorders.

Assessment of motor speech disorders in young children requires solid knowledge and expertise. That is because CAS has a number of overlapping symptoms with other speech sound disorders (e.g., severe phonological disorder, dysarthria, etc). Furthermore, symptoms which may initially appear as CAS may change during the course of intervention by the time the child is older (e.g., 3 years of age) which is why diagnosing toddlers under 3 years of age is very problematic and the use of “suspected” or “working” diagnosis is recommended (Davis & Velleman, 2000) in order to avoid misdiagnosis. Finally, the diagnosis of CAS is also problematic due to the fact that there are still to this day no valid or reliable standardized assessments sensitive to CAS detection (McCauley & Strand, 2008).

Assessment of motor speech disorders in young children requires solid knowledge and expertise. That is because CAS has a number of overlapping symptoms with other speech sound disorders (e.g., severe phonological disorder, dysarthria, etc). Furthermore, symptoms which may initially appear as CAS may change during the course of intervention by the time the child is older (e.g., 3 years of age) which is why diagnosing toddlers under 3 years of age is very problematic and the use of “suspected” or “working” diagnosis is recommended (Davis & Velleman, 2000) in order to avoid misdiagnosis. Finally, the diagnosis of CAS is also problematic due to the fact that there are still to this day no valid or reliable standardized assessments sensitive to CAS detection (McCauley & Strand, 2008).

In March 2017, Dr. Edythe Strand wrote an excellent article for the ASHA Leader entitled: “Appraising Apraxia“, in which she used a case study of a 3-year-old boy to describe how a differential diagnosis for CAS can be performed. She reviewed CAS characteristics, informal assessment protocols, aspects of diagnosis and treatment, and even included ‘Examples of Diagnostic Statements for CAS’ (which illustrate how clinicians can formulate their impressions regarding the child’s strengths and needs without explicitly labeling the child’s diagnosis as CAS).

Today, I’d like to share what information I tend to include in speech-language reports geared towards the assessing motor speech disorders in children under 3 years of age. I have a specific former client in mind for whom a differential diagnosis was particularly needed. Here’s why.

This particular 30-month client, TQ, (I did mention that I get quite a few clients for assessment around that age), was brought in due to parental concerns over her significantly reduced speech and expressive language abilities characterized by unintelligible “babbling-like” utterances and lack of expressive language. All of TQ’s developmental milestones with the exception of speech and language had been achieved grossly at age expectancy. She began limitedly producing word approximations at ~16 months of age but at 30 months of age, her verbal output was still very restricted. She mainly communicated via gestures, pointing, word approximations, and a handful of signs.

Interestingly, as an infant, she had a restricted lingual frenulum. However, since it did not affect her ability to feed, no surgical intervention was needed. Indeed, TQ presented with an adequate lingual movement for both feeding and speech sound production, so her ankyloglossia (or anterior tongue tie) was definitely not the culprit which caused her to have limited speech production.

Prior to being reevaluated by me, TQ underwent an early intervention assessment at ~26 months of age. She was diagnosed with CAS by an evaluating SLP and was found to be eligible for speech-language services, which she began receiving shortly thereafter. However, Mrs. Q noted that TQ was making very few gains in therapy and her treating SLP was uncertain regarding why her progress in therapy was so limited. Mrs. Q was also rather uncertain that TQ’s diagnosis of CAS was indeed a correct one, which was another reason why she sought a second opinion.

Prior to being reevaluated by me, TQ underwent an early intervention assessment at ~26 months of age. She was diagnosed with CAS by an evaluating SLP and was found to be eligible for speech-language services, which she began receiving shortly thereafter. However, Mrs. Q noted that TQ was making very few gains in therapy and her treating SLP was uncertain regarding why her progress in therapy was so limited. Mrs. Q was also rather uncertain that TQ’s diagnosis of CAS was indeed a correct one, which was another reason why she sought a second opinion.

Assessment of TQ’s social-emotional functioning, play skills, and receptive language (via a combination of Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000), REEL-3, & PLS-5) quickly revealed that she was a very bright little girl who was developing on target in all of the tested areas. Assessment of TQ’s expressive language (via REEL-3, PLS-5 & LUI*), revealed profoundly impaired, expressive language abilities. But due to which cause?

Despite lacking verbal speech, TQ’s communicative frequency (how often she attempted to spontaneously and appropriately initiate interactions with others), as well as her communicative intent (e.g., gaining attention, making requests, indicating protests, etc), were judged to be appropriate for her age. She was highly receptive to language stimulation given tangible reinforcements and as the assessment progressed she was observed to significantly increase the number and variety of vocalizations and word approximations including delayed imitation of words and sounds containing bilabial and alveolar nasal phonemes.

For the purpose of TQ’s speech assessment, I was interested in gaining knowledge regarding the following:

- Automatic vs. volitional control

- Simple vs. complex speech production

- Consistency of productions on repetitions of the same words/word approximations

- Vowel Productions

- Imitation abilities

- Prosody

- Phonetic inventory

- Phonotactic Constraints

- Stimulability

TQ’s oral peripheral examination yielded no difficulties with oral movements during non-speaking as well as speaking tasks. She was able to blow bubbles, stick out tongue, smile, etc as well as spontaneously vocalize without any difficulties. Her voice quality, pitch, loudness, and resonance during vocalizations and approximated utterances were judged to be appropriate for age and gender. Her prosody and fluency could not be determined due to lack of spontaneously produced continuous verbal output.

TQ’s oral peripheral examination yielded no difficulties with oral movements during non-speaking as well as speaking tasks. She was able to blow bubbles, stick out tongue, smile, etc as well as spontaneously vocalize without any difficulties. Her voice quality, pitch, loudness, and resonance during vocalizations and approximated utterances were judged to be appropriate for age and gender. Her prosody and fluency could not be determined due to lack of spontaneously produced continuous verbal output.

- Phonetic inventory of all the sounds TQ produced during the assessment is as follows:

- Consonants: plosive nasals (/m/) and alveolars (/t/, /d/, n), as well as a glide (/w/)

- Vowels: (/a/, /e/, /i/, /o/)

- TQ’s phonotactic repertoire was primarily comprised of word approximations restricted to specific sounds and consisted of CV (e.g., ne), VCV (e.g., ada), CVC (e.g., nyam), CVCV (e.g., nada), VCVC (e.g., adat), CVCVCV (nadadi), VCVCV(e.g., adada) syllable shapes

- TQ’s speech intelligibility in known and unknown contexts was profoundly reduced to unfamiliar listeners. However, her word approximations were consistent across all productions.

- Due to the above I could not perform an in-depth phonological processes analysis

However, by this time I had already formulated a working hypothesis regarding TQ’s speech production difficulties. Based on her speech sound assessment TQ presented with severe phonological disorder characterized by restricted sound inventory, simplification of sound sequences, as well as patterns of sound use errors (e.g., predominance of alveolar /d/ and nasal /n/ sounds when attempting to produce most word approximations) in speech (Stoel-Gammon, 1987).

TQ’s difficulties were not consistent with the diagnosis Childhood Apraxia of Speech (CAS) at that time due to the following:

- Adequate and varied production of vowels

- Lack of restricted use of syllables during verbalizations (TQ was observed to make verbalizations up to 3 syllables in length)

- Lack of disruptions in rate, rhythm, and stress of speech

- Frequent and spontaneous use of consistently produced verbalizations

- Lack of verbal groping behaviors when producing word-approximations

- Good control of pitch, loudness and vocal quality during vocalizations

I felt that the diagnosis of CAS was not applicable because TQ lacked a verbal lexicon and no specific phonological intervention techniques had been trialed with her during the course of her brief therapy (~4 months) to elicit word productions (Davis & Velleman, 2000; Strand, 2003). While her EI speech therapist documented that therapy has primarily focused on ‘oral motor activities to increase TQ’s awareness of her articulators and to increase imitation of oral motor movements’, I knew that until a variety of phonological/motor-speech specific interventions had been trialed over a period of time (at least ~6 months as per Davis & Velleman, 2000) the diagnosis of CAS could not be reliably made.

I felt that the diagnosis of CAS was not applicable because TQ lacked a verbal lexicon and no specific phonological intervention techniques had been trialed with her during the course of her brief therapy (~4 months) to elicit word productions (Davis & Velleman, 2000; Strand, 2003). While her EI speech therapist documented that therapy has primarily focused on ‘oral motor activities to increase TQ’s awareness of her articulators and to increase imitation of oral motor movements’, I knew that until a variety of phonological/motor-speech specific interventions had been trialed over a period of time (at least ~6 months as per Davis & Velleman, 2000) the diagnosis of CAS could not be reliably made.

I still, however, wanted to be cautious as there were a few red flags I had noted which may have potentially indicative of a non-CAS motor speech involvement, due to which I wanted to include some recommendations pertaining to motor speech remediation.

Now it is possible that after 6 months of intensive application of EBP phonological and motor speech approaches TQ would have turned 3 and still presented with highly restricted speech sound inventory and profoundly impaired speech production, making her eligible for the diagnosis of CAS in earnest. However, at the time of my assessment, making such diagnosis in view of all the available evidence would have been both clinically inappropriate and unethical.

So what were my recommendations you may ask? Well, I provisionally diagnosed TQ with a severe phonological disorder and recommended that among a variety of phonologically-based approaches to trial, an EBP approach to the treatment of motor speech disorders be also used with her for a period of 6 months to determine if it would expedite speech gains.

*For those of you who are interested in the latest EBP treatment for motor speech disorders, current evidence supports the use of the Rapid Syllable Transition Treatment (ReST). ReST is a free EBP treatment developed by the SLPs at the University of Sydney, which uses nonsense words, designed to help children coordinate movements across syllables in long words and phrases as well as helps them learn new speech movements. It is, however, important to note for young children with highly restricted sound inventories, characterized by a lack of syllable production, ReST will not be applicable. For them, the Integral Stimulation/Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cueing (DTTC) approaches do have some limited empirical support.

*For those of you who are interested in the latest EBP treatment for motor speech disorders, current evidence supports the use of the Rapid Syllable Transition Treatment (ReST). ReST is a free EBP treatment developed by the SLPs at the University of Sydney, which uses nonsense words, designed to help children coordinate movements across syllables in long words and phrases as well as helps them learn new speech movements. It is, however, important to note for young children with highly restricted sound inventories, characterized by a lack of syllable production, ReST will not be applicable. For them, the Integral Stimulation/Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cueing (DTTC) approaches do have some limited empirical support.

I also made sure to make a note in my report regarding the inappropriate use of non-speech oral motor exercises (NSOMEs) in therapy, indicating that there is NO research to support the use of NSOMEs to stimulate speech production (Lof, 2010).

In addition to the trialing of phonological and motor based approaches I also emphasized the need to establish consistent lexicon via development of functional words needed in daily communication and listed a number of examples across several categories. I made recommendations regarding select approaches and treatment techniques to trial in therapy, as well as suggestions for expansion of sounds and structures. Finally, I made suggestions for long and short term therapy goals for a period of 6 months to trial with TQ in therapy and provided relevant references to support the claims I’ve made in my report.

You may be interested in knowing that nowadays TQ is doing quite well, and at this juncture, she is still, ineligible for the diagnosis CAS (although she needs careful ongoing monitoring with respect to the development of reading difficulties when she is older).

Now I know that some clinicians will be quick to ask me: “What’s the harm in overdiagnosing CAS if the child’s speech production will still be treated via the application of motor speech production principles?” Well, aside from the fact that it’s obviously unethical and can result in terrifying the parents into obtaining all sorts of questionable and even downright harmful bunk treatments for their children, the treatment may only be limitedly appropriate, and may not result in the best possible outcomes for a particular child. To illustrate, TQ never presented with CAS and as such, while she may have initially limitedly benefited from the application of motor speech principles to address her speech production, shortly thereafter, the application of the principles of the dynamic systems theory is what brought about significant changes in her phonological repertoire.

Now I know that some clinicians will be quick to ask me: “What’s the harm in overdiagnosing CAS if the child’s speech production will still be treated via the application of motor speech production principles?” Well, aside from the fact that it’s obviously unethical and can result in terrifying the parents into obtaining all sorts of questionable and even downright harmful bunk treatments for their children, the treatment may only be limitedly appropriate, and may not result in the best possible outcomes for a particular child. To illustrate, TQ never presented with CAS and as such, while she may have initially limitedly benefited from the application of motor speech principles to address her speech production, shortly thereafter, the application of the principles of the dynamic systems theory is what brought about significant changes in her phonological repertoire.

That is why the correct diagnosis is so important for young children under 3 years of age. But before it can be made, extensive (reputable and evidence supported) training and education are needed by evaluating SLPs on the assessment and treatment of motor speech disorders in young children.

References:

- Davis, B & Velleman, S (2000). Differential diagnosis and treatment of developmental apraxia of speech in infants and toddlers”. The Transdisciplinary Journal. 10 (3): 177 – 192.

- Lof, G., & Watson, M. (2010). Five reasons why nonspeech oral-motor exercises do not work. Perspectives on School-Based Issues, 11.109-117.

- McCauley RJ, Strand EA. (2008). A Review of Standardized Tests of Nonverbal Oral and Speech Motor Performance in Children. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17,81-91.

- McCauley R.J., Strand E., Lof, G.L., Schooling T. & Frymark, T. (2009). Evidence-Based Systematic Review: Effects of Nonspeech Oral Motor Exercises on Speech, American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18, 343-360.

- Murray, E., McCabe, P. & Ballard, K.J. (2015). A Randomized Control Trial of Treatments for Childhood Apraxia of Speech. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research 58 (3) 669-686.

- Stoel-Gammon, C. (1987). Phonological skills of 2-year-olds. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 18, 323-329.

- Strand, E (2003). Childhood apraxia of speech: suggested diagnostic markers for the young child. In Shriberg, L & Campbell, T (Eds) Proceedings of the 2002 childhood apraxia of speech research symposium. Carlsbad, CA: Hendrix Foundation.

- Strand, E, McCauley, R, Weigand, S, Stoeckel, R & Baas, B (2013) A Motor Speech Assessment for Children with Severe Speech Disorders: Reliability and Validity Evidence. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, vol 56; 505-520.

Early Intervention Evaluations PART I: Assessing 2.5 year olds

Today, I’d like to talk about speech and language assessments of children under three years of age. Namely, the quality of these assessments. Let me be frank, I am not happy with what I am seeing. Often times, when I receive a speech-language report on a child under three years of age, I am struck by how little functional information it contains about the child’s linguistic strengths and weaknesses. Indeed, conversations with parents often reveal that at best the examiner spent no more than half an hour or so playing with the child and performed very limited functional testing of their actual abilities. Instead, they interviewed the parent and based their report on parental feedback alone. Consequently, parents often end up with a report of very limited value, which does not contain any helpful information on how delayed is the child as compared to peers their age.

Today, I’d like to talk about speech and language assessments of children under three years of age. Namely, the quality of these assessments. Let me be frank, I am not happy with what I am seeing. Often times, when I receive a speech-language report on a child under three years of age, I am struck by how little functional information it contains about the child’s linguistic strengths and weaknesses. Indeed, conversations with parents often reveal that at best the examiner spent no more than half an hour or so playing with the child and performed very limited functional testing of their actual abilities. Instead, they interviewed the parent and based their report on parental feedback alone. Consequently, parents often end up with a report of very limited value, which does not contain any helpful information on how delayed is the child as compared to peers their age.

So today I like to talk about what information should such speech-language reports should contain. For the purpose of this particular post, I will choose a particular developmental age at which children at risk of language delay are often assessed by speech-language pathologists. Below you will find what information I typically like to include in these reports as well as developmental milestones for children 30 months or 2.5 years of age.

Why 30 months, you may ask? Well, there isn’t really any hard science to it. It’s just that I noticed that a significant percentage of parents who were already worried about their children’s speech-language abilities when they were younger, begin to act upon those worries as the child is nearing 3 years of age and their abilities are not improving or are not commensurate with other peers their age.

Why 30 months, you may ask? Well, there isn’t really any hard science to it. It’s just that I noticed that a significant percentage of parents who were already worried about their children’s speech-language abilities when they were younger, begin to act upon those worries as the child is nearing 3 years of age and their abilities are not improving or are not commensurate with other peers their age.

So here is the information I include in such reports (after I’ve gathered pertinent background information in the form of relevant intakes and questionnaires, of course). Naturally, detailed BACKGROUND HISTORY section is a must! Prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal development should be prominently featured there. All pertinent medical history needs to get documented as well as all of the child’s developmental milestones in the areas of cognition, emotional development, fine and gross motor function, and of course speech and language. Here, I also include a family history of red flags: international or domestic adoption of the child (if relevant) as well as familial speech and language difficulties, intellectual impairment, psychiatric disorders, special education placements, or documented deficits in the areas of literacy (e.g., reading, writing, and spelling). After all, if any of the above issues are present in isolation or in combination, the risk for language and literacy deficits increases exponentially, and services are strongly merited for the child in question.

For bilingual children, the next section will cover LANGUAGE BACKGROUND AND USE. Here, I describe how many and which languages are spoken in the home and how well does the child understand and speak any or all of these languages (as per parental report based on questionnaires).

After that, I move on to describe the child’s ADAPTIVE BEHAVIOR during the assessment. In this section, I cover emotional relatedness, joint attention, social referencing, attention skills, communicative frequency, communicative intent, communicative functions, as well as any and all unusual behaviors noted during the therapy session (e.g., refusal, tantrums, perseverations, echolalia, etc.) Then I move on to PLAY SKILLS. For the purpose of play assessment, I use the Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000). In this section, I describe where the child is presently with respect to play skills, and where they actually need to be developmentally (excerpt below).

“During today’s assessment, LS’s play skills were judged to be significantly reduced for his age. A child of LS’s age (30 months) is expected to engage in a number of isolated pretend play activities with realistic props to represent daily experiences (playing house) as well as less frequently experienced events (e.g., reenacting a doctor’s visit, etc.) (corresponds to Stage VI on the Westby Play Scale, Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000)). Contrastingly, LS presented with limited repertoire routines, which were characterized primarily by exploration of toys, such as operating simple cause and effect toys (given modeling) or taking out and then putting back in playhouse toys. LS’s parents confirmed that the above play schemas were representative of play interactions at home as well. Today’s LS’s play skills were judged to be approximately at Stage II (13 – 17 months) on the Westby Play Scale, (Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000)) which is significantly reduced for a child of LS’s age, since it is almost approximately ±15 months behind his peers. Thus, based on today’s play assessment, LS’s play skills require therapeutic intervention. “

Sections on AUDITORY FUNCTION, PERIPHERAL ORAL MOTOR EXAM, VOCAL PARAMETERS, FLUENCY AND RESONANCE (and if pertinent FEEDING and SWALLOWING follow) (more on that in another post).

Now, it’s finally time to get to the ‘meat and potatoes’ of the report ARTICULATION AND PHONOLOGY as well as RECEPTIVE and EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE (more on PRAGMATIC ASSESSMENT in another post).

First, here’s what I include in the ARTICULATION AND PHONOLOGY section of the report.

- Phonetic inventory: all the sounds the child is currently producing including (short excerpt below):

- Consonants: plosive (/p/, /b/, /m/), alveolar (/t/, /d/), velar (/k/, /g/), glide (/w/), nasal (/n/, /m/) glottal (/h/)

- Vowels and diphthongs: ( /a/, /e/, /i/, /o/, /u/, /ou/, /ai/)

- Phonotactic repertoire: What type of words comprised of how many syllables and which consonant-vowel variations the child is producing (excerpt below)

- LS primarily produced one syllable words consisting of CV (e.g., ke, di), CVC (e.g., boom), VCV (e.g., apo) syllable shapes, which is reduced for a child his age.

- Speech intelligibility in known and unknown contexts

- Phonological processes analysis

Now that I have described what the child is capable of speech-wise, I discuss where the child needs to be developmentally:

“A child of LS’s age (30 months) is expected to produce additional consonants in initial word position (k, l, s, h), some consonants (t, d, m, n, s, z) in final word position (Watson & Scukanec, 1997b), several consonant clusters (pw, bw, -nd, -ts) (Stoel-Gammon, 1987) as well as evidence a more sophisticated syllable shape structure (e.g., CVCVC) Furthermore, a 30 month old child is expected to begin monitoring and repairing own utterances, adjusting speech to different listeners, as well as practicing sounds, words, and early sentences (Clark, adapted by Owens, 1996, p. 386) all of which LS is not performing at this time. Based on above developmental norms, LS’s phonological abilities are judged to be significantly below age-expectancy at this time. Therapy is recommended in order to improve LS’s phonological skills.”

At this point, I am ready to move on to the language portion of the assessment. Here it is important to note that a number of assessments for toddlers under 3 years of age contain numerous limitations. Some such as REEL-3 or Rosetti (a criterion-referenced vs. normed-referenced instrument) are observational or limitedly interactive in nature, while others such as PLS-5, have a tendency to over inflate scores, resulting in a significant number of children not qualifying for rightfully deserved speech-language therapy services. This is exactly why it’s so important that SLPs have a firm knowledge of developmental milestones! After all, after they finish describing what the child is capable of, they then need to describe what the developmental expectations are for a child this age (excerpts below).

At this point, I am ready to move on to the language portion of the assessment. Here it is important to note that a number of assessments for toddlers under 3 years of age contain numerous limitations. Some such as REEL-3 or Rosetti (a criterion-referenced vs. normed-referenced instrument) are observational or limitedly interactive in nature, while others such as PLS-5, have a tendency to over inflate scores, resulting in a significant number of children not qualifying for rightfully deserved speech-language therapy services. This is exactly why it’s so important that SLPs have a firm knowledge of developmental milestones! After all, after they finish describing what the child is capable of, they then need to describe what the developmental expectations are for a child this age (excerpts below).

RECEPTIVE LANGUAGE

“LS’s receptive language abilities were judged to be scattered between 11-17 months of age (as per clinical observations as well as informal PLS-5 and REEL-3 findings), which is also consistent with his play skills abilities (see above). During the assessment LS was able to appropriately understand prohibitive verbalizations (e.g., “No”, “Stop”), follow simple 1 part directions (when repeated and combined with gestures), selectively attend to speaker when his name was spoken (behavioral), perform a routine activity upon request (when combined with gestures), retrieve familiar objects from nearby (when provided with gestures), identify several major body parts (with prompting) on a doll only, select a familiar object when named given repeated prompting, point to pictures of familiar objects in books when named by adult, as well as respond to yes/no questions by using head shakes and head nods. This is significantly below age-expectancy.

A typically developing child 30 months of age is expected to spontaneously follow (without gestures, cues or prompts) 2+ step directives, follow select commands that require getting objects out of sight, answer simple “wh” questions (what, where, who), understand select spatial concepts, (in, off, out of, etc), understand select pronouns (e.g., me, my, your), identify action words in pictures, understand concept sizes (‘big’, ‘little’), identify simple objects according to their function, identify select clothing items such as shoes, shirt, pants, hat (on self or caregiver) as well as understand names of farm animals, everyday foods, and toys. Therapeutic intervention is recommended in order to increase LS’s receptive language abilities.

EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE:

“During today’s assessment, LS’s expressive language skills were judged to be scattered between 10-15 months of age (as per clinical observations as well as informal PLS-5 and REEL-3 findings). LS was observed to communicate primarily via proto-imperative gestures (requesting and object via eye gaze, reaching) as well as proto-declarative gestures (showing an object via eye gaze, reaching, and pointing). Additionally, LS communicated via vocalizations, head nods, and head shakes. According to parental report, at this time LS’s speaking vocabulary consists of approximately 15-20 words (see word lists below). During the assessment LS was observed to spontaneously produce a number of these words when looking at a picture book, playing with toys, and participating in action based play activities with Mrs. S and clinician. LS was also observed to produce a number of animal sounds when looking at select picture books and puzzles. For therapy planning purposes, it is important to note that LS was observed to imitate more sounds and words, when they were supported by action based play activities (when words and sounds were accompanied by a movement initiated by clinician and then imitated by LS). Today LS was observed to primarily communicate via a very limited number of imitated and spontaneous one word utterances that labeled basic objects and pictures in his environment, which is significantly reduced for his age.

A typically developing child of LS’s chronological age (30 months) is expected to possess a minimum vocabulary of 200+ words (Rescorla, 1989), produce 2-4 word utterance combinations (e.g., noun + verb, verb + noun + location, verb + noun + adjective, etc), in addition to asking 2-3 word questions as well as maintaining a topic for 2+ conversational turns. Therapeutic intervention is recommended in order to increase LS’s expressive language abilities.”

Here you have a few speech-language evaluation excerpts which describe not just what the child is capable of but where the child needs to be developmentally. Now it’s just a matter of summarizing my IMPRESSIONS (child’s strengths and needs), RECOMMENDATIONS as well as SUGGESTED (long and short term) THERAPY GOALS. Now the parents have some understanding regarding their child’s strengths and needs. From here, they can also track their child’s progress in therapy as they now have some idea to what it can be compared to.

Now I know that many of you will tell me, that this is a ‘perfect world’ evaluation conducted by a private therapist with an unlimited amount of time on her hands. And to some extent, many of you will be right! Yes, such an evaluation was a result of more than 30 minutes spent face-to-face with the child. All in all, it took probably closer to 90 minutes of face to face time to complete it and a few hours to write. And yes, this is a luxury only a few possess and many therapists in the early intervention system lack. But in the long run, such evaluations pay dividends not only, obviously, to your clients but to SLPs who perform them. They enhance and grow your reputation as an evaluating therapist. They even make sense from a business perspective. If you are well-known and highly sought after due to your evaluating expertise, you can expect to be compensated for your time, accordingly. This means that if you decide that your time and expertise are worth private pay only (due to poor insurance reimbursement or low EI rates), you can be sure that parents will learn to appreciate your thoroughness and will choose you over other providers.

Now I know that many of you will tell me, that this is a ‘perfect world’ evaluation conducted by a private therapist with an unlimited amount of time on her hands. And to some extent, many of you will be right! Yes, such an evaluation was a result of more than 30 minutes spent face-to-face with the child. All in all, it took probably closer to 90 minutes of face to face time to complete it and a few hours to write. And yes, this is a luxury only a few possess and many therapists in the early intervention system lack. But in the long run, such evaluations pay dividends not only, obviously, to your clients but to SLPs who perform them. They enhance and grow your reputation as an evaluating therapist. They even make sense from a business perspective. If you are well-known and highly sought after due to your evaluating expertise, you can expect to be compensated for your time, accordingly. This means that if you decide that your time and expertise are worth private pay only (due to poor insurance reimbursement or low EI rates), you can be sure that parents will learn to appreciate your thoroughness and will choose you over other providers.

So, how about it? Can you give it a try? Trust me, it’s worth it!

Selected References:

- Owens, R. E. (1996). Language development: An introduction (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Rescorla, L. (1989). The Language Development Survey: A screening tool for delayed language in toddlers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54, 587–599.

- Selby, J. C., Robb, M. P., & Gilbert, H. R. (2000). Normal vowel articulations between 15 and 36 months of age. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 14, 255-266.

- Stoel-Gammon, C. (1987). Phonological skills of 2-year-olds. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 18, 323-329.

- Watson, M. M., & Scukanec, G. P. (1997b). Profiling the phonological abilities of 2-year-olds: A longitudinal investigation. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 13, 3-14.

For more information on EI Assessments click on any of the below posts:

- Part II: Early Intervention Evaluations PART II: Assessing Suspected Motor Speech Disorders in Children Under 3

- Part III: Early Intervention Evaluations PART III: Assessing Children Under 2 Years of Age

- Part IV: Early Intervention Evaluations PART IV:Assessing Social Pragmatic Abilities of Children Under 3

Is it a Difference or a Disorder? Free Resources for SLPs Working with Bilingual and Multicultural Children

For bilingual and monolingual SLPs working with bilingual and multicultural children, the question of: “Is it a difference or a disorder?” arises on a daily basis as they attempt to navigate the myriad of difficulties they encounter in their attempts at appropriate diagnosis of speech, language, and literacy disorders.

For bilingual and monolingual SLPs working with bilingual and multicultural children, the question of: “Is it a difference or a disorder?” arises on a daily basis as they attempt to navigate the myriad of difficulties they encounter in their attempts at appropriate diagnosis of speech, language, and literacy disorders.

For that purpose, I’ve recently created a Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children. Its aim is to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) and Teachers in the decision-making process of how to appropriately identify bilingual/multicultural children who present with speech-language delay/deficits (vs. a language difference), for the purpose of initiating a formal speech-language-literacy evaluation. The goal is to ensure that educational professionals are appropriately identifying bilingual children for assessment and service provision due to legitimate speech language deficits/concerns, and are not over-identifying students because they speak multiple languages or because they come from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It is very important to understand that true language impairment in bilingual children will be evident in both languages from early childhood onwards, and thus will adversely affect the learning of both languages.

For that purpose, I’ve recently created a Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children. Its aim is to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) and Teachers in the decision-making process of how to appropriately identify bilingual/multicultural children who present with speech-language delay/deficits (vs. a language difference), for the purpose of initiating a formal speech-language-literacy evaluation. The goal is to ensure that educational professionals are appropriately identifying bilingual children for assessment and service provision due to legitimate speech language deficits/concerns, and are not over-identifying students because they speak multiple languages or because they come from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It is very important to understand that true language impairment in bilingual children will be evident in both languages from early childhood onwards, and thus will adversely affect the learning of both languages.

However, today the aim of today’s post is not on the above product but rather on the FREE free bilingual and multicultural resources available to SLPs online in their quest of differentiating between a language difference from a language disorder in bilingual and multicultural children.

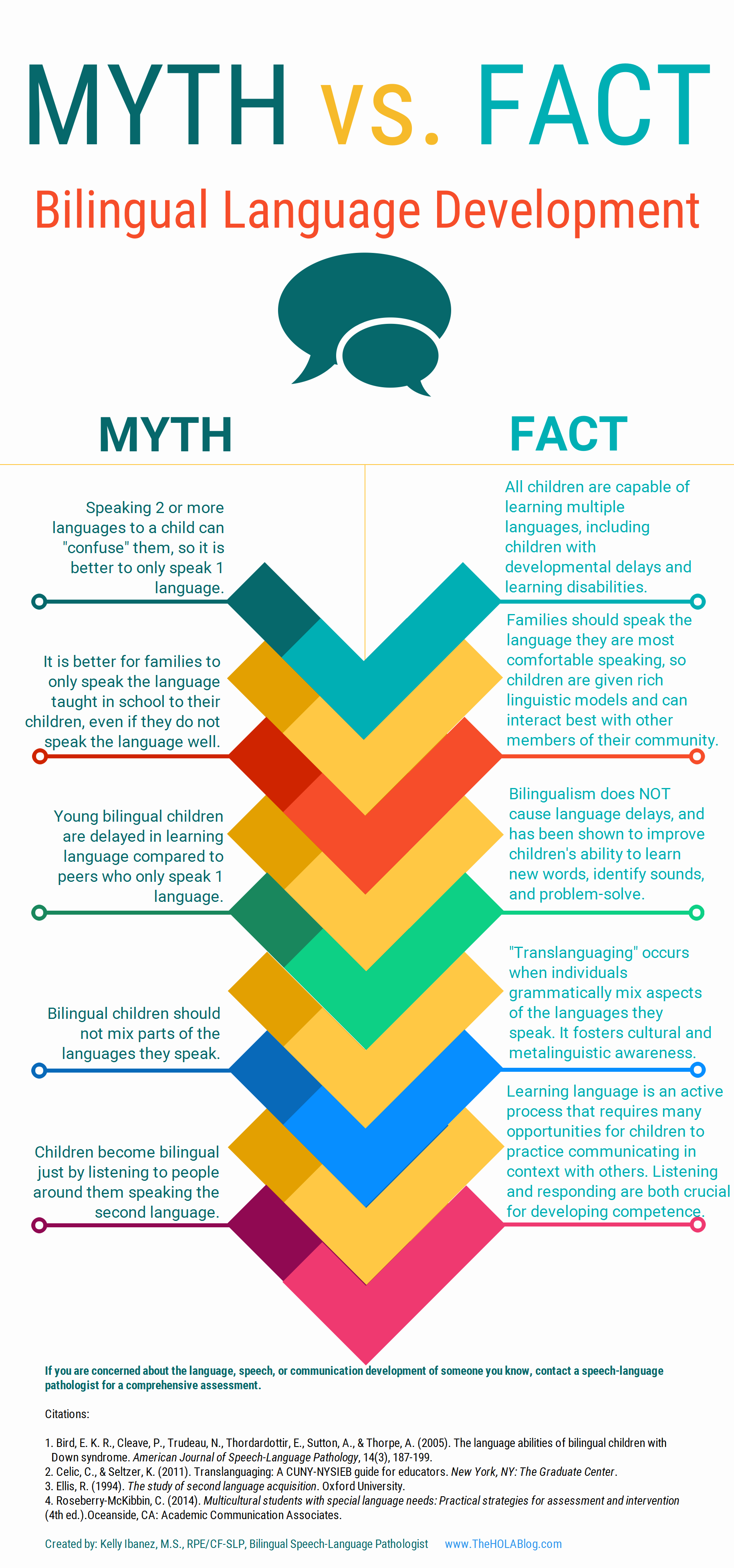

Let’s start with an excellent free infographic entitled from the Hola Blog “Myth vs. Fact: Bilingual Language Development” which was created by Kelly Ibanez, MS CCC-SLP to help dispel bilingual myths and encourage practices that promote multilingualism. Clinicians can download it and refer to it themselves, share it with other health and/or educational professionals as well as show it to parents of their clients.

Let’s start with an excellent free infographic entitled from the Hola Blog “Myth vs. Fact: Bilingual Language Development” which was created by Kelly Ibanez, MS CCC-SLP to help dispel bilingual myths and encourage practices that promote multilingualism. Clinicians can download it and refer to it themselves, share it with other health and/or educational professionals as well as show it to parents of their clients.

Let us now move on to the typical phonological development of English speaking children. After all, in order to compare other languages to English, SLPs need to be well versed in the acquisition of speech sounds in the English language. Children’s speech acquisition, developed by Sharynne McLeod, Ph.D., of Charles Sturt University, is one such resource. It contains a compilation of data on typical speech development for English speaking children, which is organized according to children’s ages to reflect a typical developmental sequence.

Next up, is a great archive which contains phonetic inventories of the various language spoken around the world for contrastive analysis purposes. The same website also contains a speech accent archive. Native and non-native speakers of English were recorded reading the same English paragraph for teaching and research purposes. It is meant to be used by professionals who are interested in comparing the accents of different English speakers.

Next up, is a great archive which contains phonetic inventories of the various language spoken around the world for contrastive analysis purposes. The same website also contains a speech accent archive. Native and non-native speakers of English were recorded reading the same English paragraph for teaching and research purposes. It is meant to be used by professionals who are interested in comparing the accents of different English speakers.

![]() Now let’s talk about one of my favorite websites, MULTILINGUAL CHILDREN’S SPEECH, also developed by Dr. Mcleod of Charles Stuart University. It contains an AMAZING plethora of resources on bilingual speech development and assessment. To illustrate, its Speech Acquisition Data includes A list of over 200 speech acquisition studies. It also contains a HUGE archive on Speech Assessments in NUMEROUS LANGUAGES as well as select assessment reviews. Finally, the website also lists in detail how aspects of speech (e.g., consonants, vowels, syllables, tones) differ between languages.

Now let’s talk about one of my favorite websites, MULTILINGUAL CHILDREN’S SPEECH, also developed by Dr. Mcleod of Charles Stuart University. It contains an AMAZING plethora of resources on bilingual speech development and assessment. To illustrate, its Speech Acquisition Data includes A list of over 200 speech acquisition studies. It also contains a HUGE archive on Speech Assessments in NUMEROUS LANGUAGES as well as select assessment reviews. Finally, the website also lists in detail how aspects of speech (e.g., consonants, vowels, syllables, tones) differ between languages.

The Leader’s Project Website is another highly informative source of FREE information on bilingual assessments, intervention, and FREE CEUS.

Now, I’d like to list some resources regarding language transfer errors.

This chart from Cengage Learning contains a nice, concise Language Guide to Transfer Errors. While it is aimed at multilingual/ESL writers, the information contained on the site is highly applicable to multilingual speakers as well.

You can also find a bonus transfer chart HERE. It contains information on specific structures such as articles, nouns, verbs, pronouns, adverbs, adjectives, word order, questions, commands, and negatives on pages 1-6 and phonemes on pages 7-8.

A final bonus chart entitled: Teacher’s Resource Guide of Language Transfer Issues for English Language Learners containing information on grammar and phonics for 10 different languages can be found HERE.

Similarly, this 16-page handout: Language Transfers: The Interaction Between English and Students’ Primary Languages also contains information on phonics and grammar transfers for Spanish, Cantonese, Vietnamese, Hmong Korean, and Khmer languages.

For SLPs working with Russian-speaking children the following links pertinent to assessment, intervention and language transference may be helpful:

For SLPs working with Russian-speaking children the following links pertinent to assessment, intervention and language transference may be helpful:

- Working with Russian-speaking clients: implications for speech-language assessment

- Strategies in the acquisition of segments and syllables in Russian-speaking children

- Language Development of Bilingual Russian/ English Speaking Children Living in the United States: A Review of the Literature

- The acquisition of syllable structure by Russian-speaking children with SLI

To determine information about the children’s language development and language environment, in both their first and second language, visit the CHESL Centre website for The Alberta Language Development Questionnaire and The Alberta Language Environment Questionnaire

There you have it! FREE bilingual/multicultural SLP resources compiled for you conveniently in one place. And since there are much more FREE GEMS online, I’d love it if you guys contributed to and expanded this modest list by posting links and title descriptions in the comments section below for others to benefit from!

Together we can deliver the most up to date evidence-based assessment and intervention to bilingual and multicultural students that we serve! Click HERE to check out the FREE Resources in the SLPs for Evidence-Based Practice Group

Helpful Bilingual Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

- Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children

- Multicultural Assessment Bundle

- Best Practices in Bilingual Literacy Assessments and Interventions

- Dynamic Assessment of Bilingual and Multicultural Learners in Speech-Language Pathology

- Practical Strategies for Monolingual SLPs Assessing and Treating Bilingual Children

- Language Difference vs. Language Disorder: Assessment & Intervention Strategies for SLPs Working with Bilingual Children

- Impact of Cultural and Linguistic Variables On Speech-Language Services

- Assessment of sound and syllable imitation in Russian-speaking infants and toddlers

- Russian Articulation Screener

- Creating Translanguaging Classrooms and Therapy Rooms

Intervention at the Last Moment or Why We Need Better Preschool Evaluations

“Well, the school did their evaluations and he doesn’t qualify for services” tells me a parent of a 3.5 year old, newly admitted private practice client. “I just don’t get it” she says bemusedly, “It is so obvious to anyone who spends even 10 minutes with him that his language is nowhere near other kids his age!” “How can this happen?” she asks frustratedly?

“Well, the school did their evaluations and he doesn’t qualify for services” tells me a parent of a 3.5 year old, newly admitted private practice client. “I just don’t get it” she says bemusedly, “It is so obvious to anyone who spends even 10 minutes with him that his language is nowhere near other kids his age!” “How can this happen?” she asks frustratedly?

This parent is not alone in her sentiment. In my private practice I frequently see preschool children with speech language impairments who for all intents and purposes should have qualified for preschool- based speech language services but do not due to questionable testing practices.

To illustrate, several years ago in my private practice, I started seeing a young preschool girl, 3.2 years of age. Just prior to turning 3, she underwent a collaborative school-based social, psychological, educational, and speech language evaluation. The 4 combined evaluators from each field only used one standardized assessment instrument “The Battelle Developmental Inventory – Second Edition (BDI-2)” along with a limited ‘structured observation’, without performing any functional or dynamic assessments and found the child to be ineligible for services on account of a low average total score on the BDI-2.

However, during the first session working 1:1 with this client at the age of 3.2 a number of things became very apparent. The child had very limited highly echolalic verbal output primarily composed of one-word utterances and select two-word phrases. She had highly limited receptive vocabulary and could not consistently point to basic pictures denoting common household objects and items (e.g., chair, socks, clock, sun, etc.) Similarly, expressively she exhibited a number of inconsistencies when labeling simple nouns (e.g., called tree a flower, monkey a dog, and sofa a chair, etc.) Clearly this child’s abilities were nowhere near age level, so how could she possibly not qualify for preschool based services?

Further work with the child over the next several years yielded slow, labored, and inconsistent gains in the areas of listening, speaking, and social communication. I’ve also had a number of concerns regarding her intellectual abilities that I had shared with the parents. Finally, two years after preschool eligibility services were denied to this child, she underwent a second round of re-evaluations with the school district at the age of 5.2.

This time around she qualified with bells on! The same speech language pathologist and psychologist who assessed her first time around two years ago, now readily documented significant communication (Preschool Language Scale-5-PLS-5 scores in the 1st % of functioning) and cognitive deficits (Full Scale Intelligence Quotient-FSIQ in low 50’s).

Here is the problem though. This is not a child who had suddenly regressed in her abilities. This is a child who actually had improved her abilities in all language domains due to private language therapy services. Her deficits very clearly existed at the time of her first school-based assessment and had continued to persist over time. For the duration of two years this child could have significantly benefited from free and appropriate education in school setting, which was denied to her due to highly limited preschool assessment practices.

Today, I am writing this post to shed light on this issue, which I’m pretty certain is not just confined to the state of New Jersey. I am writing this post not simply to complain but to inform parents and educators alike on what actually constitutes an appropriate preschool speech-language assessment.

As per NJAC 6A:14-2.5 Protection in evaluation procedures (pgs. 29-30)

As per NJAC 6A:14-2.5 Protection in evaluation procedures (pgs. 29-30)

(a) In conducting an evaluation, each district board of education shall:

- Use a variety of assessment tools and strategies to gather relevant functional and developmental information, including information:

- Provided by the parent that may assist in determining whether a child is a student with a disability and in determining the content of the student’s IEP; and

- Related to enabling the student to be involved in and progress in the general education curriculum or, for preschool children with disabilities, to participate in appropriate activities;

- Not use any single procedure as the sole criterion for determining whether a student is a student with a disability or determining an appropriate educational program for the student; and

- Use technically sound instruments that may assess the relative contribution of cognitive and behavioral factors, in addition to physical or developmental factors.

Furthermore, according to the New Special Education Code: N.J.A.C. 6A:14-3.5(c)10 (please refer to your state’s eligibility criteria to find similar guidelines) the eligibility of a “preschool child with a disability” applies to any student between 3-5 years of age with an identified disabling condition adversely affecting learning/development (e.g., genetic syndrome), a 33% delay in one developmental area, or a 25% percent delay in two or more developmental areas below :

- Physical, including gross/fine motor and sensory (vision and hearing)

- Intellectual

- Communication

- Social/emotional

- Adaptive

These delays can be receptive (listening) or expressive (speaking) and need not be based on a total test score but rather on all testing findings with a minimum of at least two assessments being performed. A determination of adverse impact in academic and non-academic areas (e.g., social functioning) needs to take place in order for special education and related services be provided. Additionally, a delay in articulation can serve as a basis for consideration of eligibility as well.

These delays can be receptive (listening) or expressive (speaking) and need not be based on a total test score but rather on all testing findings with a minimum of at least two assessments being performed. A determination of adverse impact in academic and non-academic areas (e.g., social functioning) needs to take place in order for special education and related services be provided. Additionally, a delay in articulation can serve as a basis for consideration of eligibility as well.

Moreover, according to the State Education Agencies Communication Disabilities Council (SEACDC) Consulatent for NJ – Fran Liebner, the BDI-2 is not the only test which can be used to determine eligibility, since the nature and scope of the evaluation must be determined based on parent, teacher and IEP team feedback.

In fact, New Jersey’s Special Education Code, N.J.A.C. 6A:14 prescribes no specific test in its eligibility requirements. While it is true that for NJ districts participating in Indicator 7 (Preschool Outcomes) BDI-2 is a required collection tool it does NOT preclude the team from deciding what other diagnostic tools are needed to assess all areas of suspected disability to determine eligibility.

Speech pathologists have many tests available to them when assessing young preschool children 2 to 6 years of age.

SELECT SPEECH PATHOLOGY TESTS FOR PRESCHOOL CHILDREN (2-6 years of age)

Articulation:

- Sunny Articulation Test (SAPT)** Ages: All (nonstandardized)

- Clinical Assessment of Articulation and Phonology-2 (CAAP-2) Ages: 2.6+

- Linguisystems Articulation Test (LAT) Ages: 3+

- Goldman Fristoe Test of Articulation-3 (GFTA-3) Ages: 2+

Fluency:

- Stuttering Severity Instrument -4 (SSI-4) Ages: 2+

- Test of Childhood Stuttering (TOCS) Ages 4+

General Language:

General Language:

- Preschool Language Assessment Instrument-2 (PLAI-2) Ages: 3+

- Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals -Preschool 2 (CELF-P2) Ages: 3+

- Test of Early Language Development, Third Edition (TELD-3) Ages: 2+

- Test of Auditory Comprehension of Language Third Edition (TACL-4) Ages: 3+

- Preschool Language Scale-5 (PLS-5)* (use with extreme caution) Ages: Birth-7:11

Vocabulary

- Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test-4 (ROWPVT-4) Ages 2+

- Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test-4 (EOWPVT-4) Ages 2+

- Montgomery Assessment of Vocabulary Acquisition (MAVA) 3+

- Test of Word Finding-3 (TWF-3) Ages 4.6+

Auditory Processing and Phonological Awareness

- Auditory Skills Assessment (ASA) Ages 3:6+

- Test of Auditory Processing Skills-3 (TAPS-3) Ages 4+

- Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing-2 (CTOPP-2) Ages 4+

Pragmatics/Social Communication

Pragmatics/Social Communication

- Language Use Inventory LUI (O’Neil, 2009) Ages 18-47 months

- Children’s Communication Checklist-2 (CCC-2) (Bishop, 2006) Ages 4+

In addition to administering standardized testing SLPs should also use play scales (e.g., Westby Play Scale, 1980) to assess the given child’s play abilities. This is especially important given that “play—both functional and symbolic has been associated with language and social communication ability.” (Toth, et al, 2006, pg. 3)

Finally, by showing children simple wordless picture books, SLPs can also obtain of wealth of information regarding the child’s utterance length, as well as narrative abilities ( a narrative assessment can be performed on a verbal child as young as two years of age).

Finally, by showing children simple wordless picture books, SLPs can also obtain of wealth of information regarding the child’s utterance length, as well as narrative abilities ( a narrative assessment can be performed on a verbal child as young as two years of age).

Comprehensive school-based speech-language assessments should be the norm and not an exception when determining preschoolers eligibility for speech language services and special education classification.

Consequently, let us ensure that our students receive fair and adequate assessments to have access to the best classroom placements, appropriate accommodations and modifications as well as targeted and relevant therapeutic services. Anything less will lead to the denial of Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE) to which all students are entitled to!

Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Resources Pertaining to Preschoolers:

- Pediatric History Questionnaire

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist For Preschool Children

- Language Processing Checklist for Preschool Children 3:0-5:11 Years of Age

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for Preschool Children

- Recognizing the Warning Signs of Social Emotional Difficulties in Language Impaired Toddlers and Preschoolers

- Narrative Assessment Bundle

- Behavior Management Strategies for Speech Language Pathologists

- Effective Behavior Management Techniques for Parents and Professionals

- Executive Function Impairments in At-Risk Pediatric Populations

- General Assessment and Treatment Start Up Bundle

- Comprehensive Assessment of Monolingual and Bilingual Children with Down Syndrome

- Multicultural Assessment Bundle

- Creating A Learning Rich Environment for Language Delayed Preschoolers

- Strategies of Language Facilitation with Picture Books For Parents and Professionals

- Assessment of sound and syllable imitation in Russian speaking infants and toddlers

- Russian Articulation Screener

Why Do I Have to Tell You What’s Wrong with My Child? Or On the Importance of Targeted Assessments

A few days ago I received a phone call from a parent who was seeking a language evaluation for her child. As it is my policy with all assessments, I asked her to fill out an intake and a checklist to identify her child’s specific areas of difficulty in order to compile a comprehensive and targeted testing battery. Her response to me was: “I’ve never heard of this before? Why do I have to tell you what’s wrong with my child? Why can’t you figure it out?” Similarly, last week, another parent has questioned: “So you can’t do the assessment without this form?” Given the above questions, and especially because May is a Better Hearing and Speech Month #BHSM, during which it is important to raise awareness about communication disorders, I want to take this time to explain to parents why performing targeted speech language assessments is SO CRUCIAL.

To begin with it is very important to understand that speech and language can be analyzed in many different ways beyond looking at pronunciation, vocabulary or listening and speaking skills.

Targeted areas within the scope of practice of pediatric school based speech language pathologists include the assessment of:

- SPEECH

- The child may have difficulties with pronunciation of sounds in words, stutter, clutter, have a lisp or have difficulties in the areas of voice, prosody, or resonance. For the majority of the above difficulties completely different tests and testing procedures may be needed in order to appropriately assess the child.

- LANGUAGE

- Receptive Language

- Ability to follow directions, answer questions, recall sentences, understand verbal messages, as well as comprehend orally presented text

- Memory and Attention

- Also see executive function skills

- Expressive Language

- Vocabulary knowledge and use, formulation of words and sentences as well as production of narratives or stories

- Problem Solving

- Verbal reasoning and critical thinking skills are very important for successful independent decision making as well as for interpretation of academically based texts and complete assignments

- Pragmatic Language

- Successful use of language for a variety of communicative purposes

- Initiate and maintain topics, maintain conversational exchanges, request help, etc

- Successful use of language for a variety of communicative purposes

- Social Emotional Competence

- Effective interpersonal negotiation skills, compromise and negotiation abilities, as well as perspective taking are integral to academic and social success. These abilities are often compromised in children with language disorders and require a thorough assessment

- Executive Functions (EFs)

- These are higher level cognitive processes involved in inhibition of thought, action and emotion, which are located in the prefrontal cortex of the frontal lobe of the brain.

- Major EF components include working memory, inhibitory control, planning, and set-shifting. EFs contribute to child’s ability to sustain attention, ignore distractions, and succeed in academic settings.

- Receptive Language

- READING DISABILITIES AND DYSLEXIA

- Phonological Awareness

- Reading Ability

- Writing

- Spelling

One General Language Test Does Not Fit All!

Children with speech and language disorders do not necessarily display weaknesses in all affected areas but may only display difficulties in selected few.

To illustrate, high functioning students on the autistic spectrum may have very strong academic skills related to comprehension and expression of language but may display significant social pragmatic language weaknesses, which will not be apparent on general language testing (e.g., administration of Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals -5). Thus, the administration of a general language test will be contraindicated for these students as it will only show typical performance on these tests and will not qualify them for targeted language based services that they need. However, by administering to them a testing battery composed of tests sensitive to social pragmatic language competence will highlight their areas of difficulty and result in a creation of a targeted intervention plan to improve their abilities in the affected areas.

Similarly, children at risk for reading disabilities will not benefit from the administration of general language testing either, since their deficits may lie in the areas of sound discrimination, isolation, or blending as well as as impaired decoding ability. So the administration of tests sensitive to phonological awareness and emergent reading ability would be much more relevant.

This is exactly why taking an extra step and filling out a simple form will result in a much more targeted and beneficial speech language assessment for the child. The goal of any competent professional assessment is to eliminate the administration of unnecessary and irrelevant tests and focus only on the administration of instruments directly targeting the areas of difficulty that the child presents with. Given the fact that assessment of language covers so many broad areas, it makes perfect sense to ask parents to fill out relevant checklists/intakes as a routine part of a pre-assessment procedure. Otherwise, even after observations in school setting, I would still just be blindly ‘fishing’ for deficits without really knowing whether I will ‘accidentally stumble upon them’ using a general test at hand.

Of course, even checklists need to be targeted by age and areas of functioning. Here’s how I use mine. When performing comprehensive fist time assessments I ask the parent to fill out the comprehensive checklists based on the child’s age. These are broken down as follows:

- Early Intervention (0-36 months)

- Preschool (3-5:11 years of age)

- School-Age (6:0-11;11 years of age)

- Adolescent (12-18 years of age)

However, oftentimes when I perform reassessments or second opinion evaluations, I may ask the parent to fill out checklists pertaining to specific, known, areas of difficulty. These currently include:

After the parent fills the checklist out, the child’s areas of difficulty literally jump out from the pages. Now, all I need to do is to choose the appropriate testing instruments, which will BEST help me determine the exact nature and cause of the child’s deficits and I am all set. I administer the testing, interpret the results and write a comprehensive report detailing which therapy goals will be targeted. And this is why pre-assessment checklist administration is so important.

Helpful Resources:

- The Checklists Bundle

- Assessment Checklist for Preschool-Aged Children

- Assessment Checklist for School-Aged Children

- Speech Language Assessment Checklist for Adolescents

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for Preschool Children

- Social Pragmatic Deficits Checklist for School-Aged Children

- Language Processing Deficits Checklist for School-Aged Children

Articulation Assessment ToolKt

In February 2013 I did a review of the Sunny Articulation Test by Smarty Apps. At that time I really liked the test but felt that a few enhancements could really make it standout from other available articulation tests and test apps on the market. Recently, the developer, Barbara Fernandes, contacted me again and asked me to take a second look at the new and improved Sunny Articulation and Phonology Kit (SAPT-K), which is what I am doing today. Continue reading Articulation Assessment ToolKt

In February 2013 I did a review of the Sunny Articulation Test by Smarty Apps. At that time I really liked the test but felt that a few enhancements could really make it standout from other available articulation tests and test apps on the market. Recently, the developer, Barbara Fernandes, contacted me again and asked me to take a second look at the new and improved Sunny Articulation and Phonology Kit (SAPT-K), which is what I am doing today. Continue reading Articulation Assessment ToolKt

Articulation Carnival-App Review and Giveaway

Today I am reviewing a brand new app by the Virtual Speech Center -Articulation Carnival (requires iOS 7 or later; compatible with iPad). Virtual Speech Center did a great job creating a fun app, where the kids get to go to a “carnival’ and practice their articulation at the word, phrase, and sentence levels.

Much like all their other apps, this one is super easy to use and very intuitive to navigate. With a variety of options to boot. Applicable to children of all ages beginning with 2+ years, it’s phoneme targets include 20 pictures per phoneme and per word position as well as phrases and sentences. All phonemes are editable which is a very convenient options for therapists who need to customize their client’s phoneme lists based on the child’s present level of ability and needs. Continue reading Articulation Carnival-App Review and Giveaway

Tips Corner: Creating Opportunities for Spontaneous and Functional Communication

In today’s guest post, Natalie Romanchukevich advises readers on how to create opportunities to expand children’s spontaneous communication skills.

In today’s guest post, Natalie Romanchukevich advises readers on how to create opportunities to expand children’s spontaneous communication skills.

Helping young children build speech- language skills is an exciting job that both caregivers and educators try to do every second of the day. We spend so much time giving our children directions to follow, asking them a ton of questions, and modeling words and phrases to shape them into eloquent communicators.

What I find we do NOT do enough, sometimes, is hold back on our never ending “models” of what or how to say things, questions, and directions, instead of allowing our children initiate and engage with us. Greenspan refers to these initiations as opening circles of communication (Weirder & Greenspan “Engaging Autism”, 2006).

Speech- language development can be thought of as having three interacting and equally important domains- Form ,Content, and Use (Lahey, 1988).

Form refers to the grammatical correctness of our words and sentences (eat vs. eat+ ing).

Content is what the we are essentially communicating- the meaning of our words and sentences.

Use (also known as pragmatics) refers to the function of our words or for what purpose we are using them.

The communicative functions that slowly emerge and characterize communication over the course of language acquisition in vary in typically developing young children. Children communicate to greet others, comment on objects/actions, request desired objects, request assistance, protest, deny (a statement), ask questions, regulate others (e.g. “blow!”, “open!”), entertain, and narrate events.

In order for children to be able to express these functions, aside from the intent to communicate, there must also be opportunities to express ideas, wants, needs. For example, why would Timmy request for an object (nonverbally or verbally) if the caregiver hands everything to the child at the slightest sign of a tantrum. Why ask a “where?” question if every toy or beloved object is comfortably in sight? Why ask for help if the caregiver readily assists the child with all activities. The educators describe it as assuming the child’s needs.

Of course we do it out of love and care for the child, and, let’s be honest, sometimes, to save time. However, it is important with both typical and delayed children to be mindful of what (form, content, use) we model, when (timing is crucial in teaching) we model it, how (facial expression, tone of voice, etc) we model it, and why (is it developmentally important to teach it now?) we model it at this very moment.

Just as it is important for kids to comprehend concepts, follow directions, and understand the different wh- questions, it is also paramount that your child is able to initiate communication. After all, communication is the ability to express ideas, thoughts, and wants, not just understand those expressed by others. Answering questions and following commands is not initiating. Language that is elicited by us- is not spontaneous.

To use language spontaneously, effortlessly and creatively, children need opportunities to practice the skill, to experience taking the lead. In order for our children to get there, we must first offer models of how to initiate communication and do so appropriately. We can then create opportunities for the child to speak up.

The most basic strategies you can use to encourage spontaneous initiations (whether nonverbal or verbal) may seem seem initially as counterintuitive. I mean what is the point to introducing attractive new toys or displaying a yummy snack and then putting it away? Yet it is exactly that action which may very much encourage your child to run after you with gestures or words. Even then, you may still choose to play “dumb” and be “unsure” as to what it is your child wants. Does s/he want that bag with new toy or snack “opened?” and “out?”

If the child is nonverbal, his use of gestures to regulate your actions to get the desired item out and open may be the child’s initial step toward sound imitation. If you are working on getting the child to request help (not just objects), here is your opportunity to model “help” if the child can’t open the item independently. On a side note, I often hear educators model “help me please!” when the child is clearly at a single word level. This is not a developmental way of teaching. Yes, it is nice to hear a full sentence but your child may not be ready for it.

While playing with your child and actively commenting on your joint play, you may find it productive to suddenly become quiet and cease all attempts to ask questions. This often works beautifully in my therapy sessions; usually, after I have engaged the child into some sort of cooperative and enjoyable play! But it takes a conscious effort and self-control on the part of the adult, since we are so used to engaging in this adult- directed (telling the child what to do as opposed to letting him/her lead and you follow) approach to teaching.

However, once you are able to contain your speech and actions (I promise you it is possible), you may be surprised to hear some immediate or delayed imitations of words/ phrases as well as spontaneous meaningful language. The language produced, to me, is an indication that the child wants more of the experience- more language enriched play. Use this opportunity to expand on what s/he is already saying.

Here, timing is really important as you want to imitate back everything your child is doing. This is another way to communicate with your child. Build on your child’s language to further describe the objects or people in play without using long sentences. So, allowing nothing to happen for a few minutes at a time may just be the push to help your child come out with some form of communication.

In addition, stopping a novel activity or toy exploration at the very height of your child’s excitement also works well with many children. You don’t have to be confrontational about it, “if you don’t imitate my word/ phrase I just won’t give it back to you”. make sure to create these “obstructions”, as Greenspan refers to them, in a friendly, playful and positive manner. Obstructions or fabricated “problems” are also a big part of social-cognitive and constructivist theories of language learning.

The idea behind these “obstructions” is that the children are forced to problem solve and use resources (language being one of them!) so they can get what they want. Allowing your child to problem solve is critical to overall cognitive development that affects and shapes speech and language. Presenting your child with developmentally appropriate activities that involve thinking and figuring out of how to get X is an invaluable strategy that I always use with all of my children.

In sum, stop access to items that are already loved, tape up containers, close boxes and jars with favorite snack and toys, give your child all but ONE important item that is needed to complete an activity (glue, scissors), give your child the “wrong” item, or offer the “wrong” solution to the problem. All of these “problems” will push the kid to think and figure out what to do next. This, in turn, facilitates spontaneous language use.

Letting go of control and just allowing for things to spill, break, or simply not follow the predictable comfortable routine, too, elicits a ton of speech- language and fun communication. These are the most teachable moments as our children experience all the new words and concepts first hand. Perhaps, this is why many children learn “dirty” or “wet” attributes before they learn their colors. These concepts are more easily learned because they are experiential and bring about relevant words to describe these personally relevant and emotional experiences. Cleaning up and taking turns arranging things back in place is super educational too as our children need to learn responsibility and helping others.

Moreover, exposing children to objects that are completely novel and foreign (but safe!) may help elicit an attempt to ask a question “what this?” because the child wants to know. The motivation is there. Now s/he needs language to get the answer from you. Some children may use a word with a rising intonation, which too is a question form, just not grammatically mature one. For example, “Hat?” is as much of a question as “Is that a hat?!”. If all your child is capable of verbalizing is “wow”, then you can go ahead and model “what IS that?” question a few times. Of course, you want to pair it up with an exaggerated expression of surprise and excitement in your voice.