Language Difference vs. Language Disorder: Assessment & Intervention Strategies for SLPs Working with Bilingual Children

It’s DAY 25 of my Birthday Month Giveaways and I am raffling off a giveaway by Teach Speech 365, which is There was a Silly SLP who Got Stuck to Some Categories .

It’s DAY 25 of my Birthday Month Giveaways and I am raffling off a giveaway by Teach Speech 365, which is There was a Silly SLP who Got Stuck to Some Categories .

This catchy little mini-book activity targets categorization skills. The silly SLP gets stuck on all sorts of things. There is also a complementary silly male SLP [named Sam] which contains the same activities!

Packet Contents:

You can find this product in Teach Speech 365 TPT store by clicking HERE or you can enter my giveaway for a chance to win.

a Rafflecopter giveaway

To date, I have written 3 posts on speech and language assessments of children under 3 years of age. My first post offered suggestions on what information to include in general speech-language assessments for this age group, my second post specifically discussed assessments of toddlers with suspected motor speech disorders and my third post described what information I tend to include in reports for children ~16-18 months of age.

To date, I have written 3 posts on speech and language assessments of children under 3 years of age. My first post offered suggestions on what information to include in general speech-language assessments for this age group, my second post specifically discussed assessments of toddlers with suspected motor speech disorders and my third post described what information I tend to include in reports for children ~16-18 months of age.

Today, I’d like to offer some suggestions on the assessment of social emotional functioning and pragmatics of children, ages 3 and under.

For starters, below is the information I found compiled by a number of researchers on select social pragmatic milestones for the 0-3 age group:

3. Development of Theory of Mind (Westby, 2014)

In my social pragmatic assessments of the 0-3 population, in addition, to the child’s adaptive behavior during the assessment, I also describe the child’s joint attention, social emotional reciprocity, as well as social referencing abilities.

Joint attention is the shared focus of two individuals on an object. Responding to joint attention refers to the child’s ability to follow the direction of the gaze and gestures of others in order to share a common point of reference. Initiating joint attention involves child’s use of gestures and eye contact to direct others’ attention to objects, to events, and to themselves. The function of initiating joint attention is to show or spontaneously seek to share interests or pleasurable experience with others. (Mundy, et al, 2007)

Social emotional reciprocity involves being aware of the emotional and interpersonal cues of others, appropriately interpreting those cues, responding appropriately to what is interpreted as well as being motivated to engage in social interactions with others (LaRocque and Leach,2009).

Social referencing refers to a child’s ability to look at a caregiver’s cues such as facial expressions, body language and tone of voice in an ambiguous situation in order to obtain clarifying information. (Walden & Ogan, 1988)

Here’s a brief excerpt from an evaluation of a child ~18 months of age:

“RA’s joint attention skills, social emotional reciprocity as well as social referencing were judged to be appropriate for his age. For example, when Ms. N let in the family dog from the deck into the assessment room, RA immediately noted that the dog wanted to exit the room and go into the hallway. However, the door leading to the hallway was closed. RA came up to the closed door and attempted to reach the doorknob. When RA realized that he cannot reach to the doorknob to let the dog out, he excitedly vocalized to get Ms. N’s attention, and then indicated to her in gestures that the dog wanted to leave the room.”

If I happen to know that a child is highly verbal, I may actually include a narrative assessment, when evaluating toddlers in the 2-3 age group. Now, of course, true narratives do not develop in children until they are bit older. However, it is possible to limitedly assess the narrative abilities of verbal children in this age group. According to Hedberg & Westby (1993) typically developing 2-year-old children are at the Heaps Stage of narrative development characterized by

If I happen to know that a child is highly verbal, I may actually include a narrative assessment, when evaluating toddlers in the 2-3 age group. Now, of course, true narratives do not develop in children until they are bit older. However, it is possible to limitedly assess the narrative abilities of verbal children in this age group. According to Hedberg & Westby (1993) typically developing 2-year-old children are at the Heaps Stage of narrative development characterized by

In contrast, though typically developing children between 2-3 years of age in the Sequences Stage of narrative development still arbitrarily link story elements together without transitions, they can:

To illustrate, below is a narrative sample from a typically developing 2-year-old child based on the Mercer Mayer’s classic wordless picture book: “Frog Where Are You?”

To illustrate, below is a narrative sample from a typically developing 2-year-old child based on the Mercer Mayer’s classic wordless picture book: “Frog Where Are You?”

Of course, a play assessment for this age group is a must. Since, in my first post, I offered a play skills excerpt from one of my early intervention assessments and in my third blog post, I included a link to the Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000), I will now move on to the description of a few formal instruments I find very useful for this age group.

Of course, a play assessment for this age group is a must. Since, in my first post, I offered a play skills excerpt from one of my early intervention assessments and in my third blog post, I included a link to the Revised Westby Play Scale (Westby, 2000), I will now move on to the description of a few formal instruments I find very useful for this age group.

While some criterion-referenced instruments such as the Rossetti, contain sections on Interaction-Attachment and Pragmatics, there are other assessments which I prefer for evaluating social cognition and pragmatic abilities of toddlers.

For toddlers 18+months of age, I like using the Language Use Inventory (LUI) (O’Neill, 2009) which is administered in the form of a parental questionnaire that can be completed in approximately 20 minutes. Aimed at identifying children with delay/impairment in pragmatic language development it contains 180 questions and divided into 3 parts and 14 subscales including:

For toddlers 18+months of age, I like using the Language Use Inventory (LUI) (O’Neill, 2009) which is administered in the form of a parental questionnaire that can be completed in approximately 20 minutes. Aimed at identifying children with delay/impairment in pragmatic language development it contains 180 questions and divided into 3 parts and 14 subscales including:

Therapists can utilize the Automated Score Calculator, which accompanies the LUI in order to generate several pages write up or summarize the main points of the LUI’s findings in their evaluation reports.

Below is an example of a summary I wrote for one of my past clients, 35 months of age.

AN’s ability to use language was assessed via the administration of the Language Use Inventory (LUI). The LUI is a standardized parental questionnaire for children ages 18-47 months aimed at identifying children with delay/impairment in pragmatic language development. Composed of 3 parts and 14 subscales it focuses on how the child communicates with gestures, words and longer sentences.

On the LUI, AN obtained a raw score of 53 and a percentile rank of <1, indicating profoundly impaired performance in the area of language use. While AN scored in the average range in the area of varied word use, deficits were noted with requesting help, word usage for notice, lack of questions and comments regarding self and others, lack of reciprocal word usage in activities with others, humor relatedness, adapting to conversations to others, as well as difficulties with building longer sentences and stories.

Based on above results AN presents with significant social pragmatic language weaknesses characterized by impaired ability to use language for a variety of language functions (initiate, comment, request, etc), lack of reciprocal word usage in activities with others, humor relatedness, lack of conversational abilities, as well as difficulty with spontaneous sentence and story formulation as is appropriate for a child his age. Therapeutic intervention is strongly recommended to improve AN’s social pragmatic abilities.

In addition to the LUI, I recently discovered the Theory of Mind Inventory-2. The ToMI-2 was developed on a normative sample of children ages 2 – 13 years. For children between 2-3 years of age, it offers a 14 question Toddler Screen (shared here with author’s permission). While due to the recency of my discovery, I have yet to use it on an actual client, I did have fun creating a report with it on a fake client.

In addition to the LUI, I recently discovered the Theory of Mind Inventory-2. The ToMI-2 was developed on a normative sample of children ages 2 – 13 years. For children between 2-3 years of age, it offers a 14 question Toddler Screen (shared here with author’s permission). While due to the recency of my discovery, I have yet to use it on an actual client, I did have fun creating a report with it on a fake client.

First, I filled out the online version of the 14 question Toddler Screen (paper version embedded in the link above for illustration purposes). Typically the parents are asked to place slashes on the form in relevant areas, however, the online version requested that I use numerals to rate skill acquisition, which is what I had done. After I had entered the data, the system generated a relevant report for my imaginary client. In addition to the demographic section, the report generated the following information (below):

I find the information provided to me by the Toddler Screen highly useful for assessment and treatment planning purposes and definitely have plans on using this portion of the TOM-2 Inventory as part of my future toddler evaluations.

Of course, the above instruments are only two of many, aimed at assessing social pragmatic abilities of children under 3 years of age, so I’d like to hear from you! What formal and informal instruments are you using to assess social pragmatic abilities of children under 3 years of age? Do you have a favorite one, and if so, why do you like it?

References:

For bilingual and monolingual SLPs working with bilingual and multicultural children, the question of: “Is it a difference or a disorder?” arises on a daily basis as they attempt to navigate the myriad of difficulties they encounter in their attempts at appropriate diagnosis of speech, language, and literacy disorders.

For bilingual and monolingual SLPs working with bilingual and multicultural children, the question of: “Is it a difference or a disorder?” arises on a daily basis as they attempt to navigate the myriad of difficulties they encounter in their attempts at appropriate diagnosis of speech, language, and literacy disorders.

For that purpose, I’ve recently created a Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children. Its aim is to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) and Teachers in the decision-making process of how to appropriately identify bilingual/multicultural children who present with speech-language delay/deficits (vs. a language difference), for the purpose of initiating a formal speech-language-literacy evaluation. The goal is to ensure that educational professionals are appropriately identifying bilingual children for assessment and service provision due to legitimate speech language deficits/concerns, and are not over-identifying students because they speak multiple languages or because they come from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It is very important to understand that true language impairment in bilingual children will be evident in both languages from early childhood onwards, and thus will adversely affect the learning of both languages.

For that purpose, I’ve recently created a Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children. Its aim is to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) and Teachers in the decision-making process of how to appropriately identify bilingual/multicultural children who present with speech-language delay/deficits (vs. a language difference), for the purpose of initiating a formal speech-language-literacy evaluation. The goal is to ensure that educational professionals are appropriately identifying bilingual children for assessment and service provision due to legitimate speech language deficits/concerns, and are not over-identifying students because they speak multiple languages or because they come from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It is very important to understand that true language impairment in bilingual children will be evident in both languages from early childhood onwards, and thus will adversely affect the learning of both languages.

However, today the aim of today’s post is not on the above product but rather on the FREE free bilingual and multicultural resources available to SLPs online in their quest of differentiating between a language difference from a language disorder in bilingual and multicultural children.

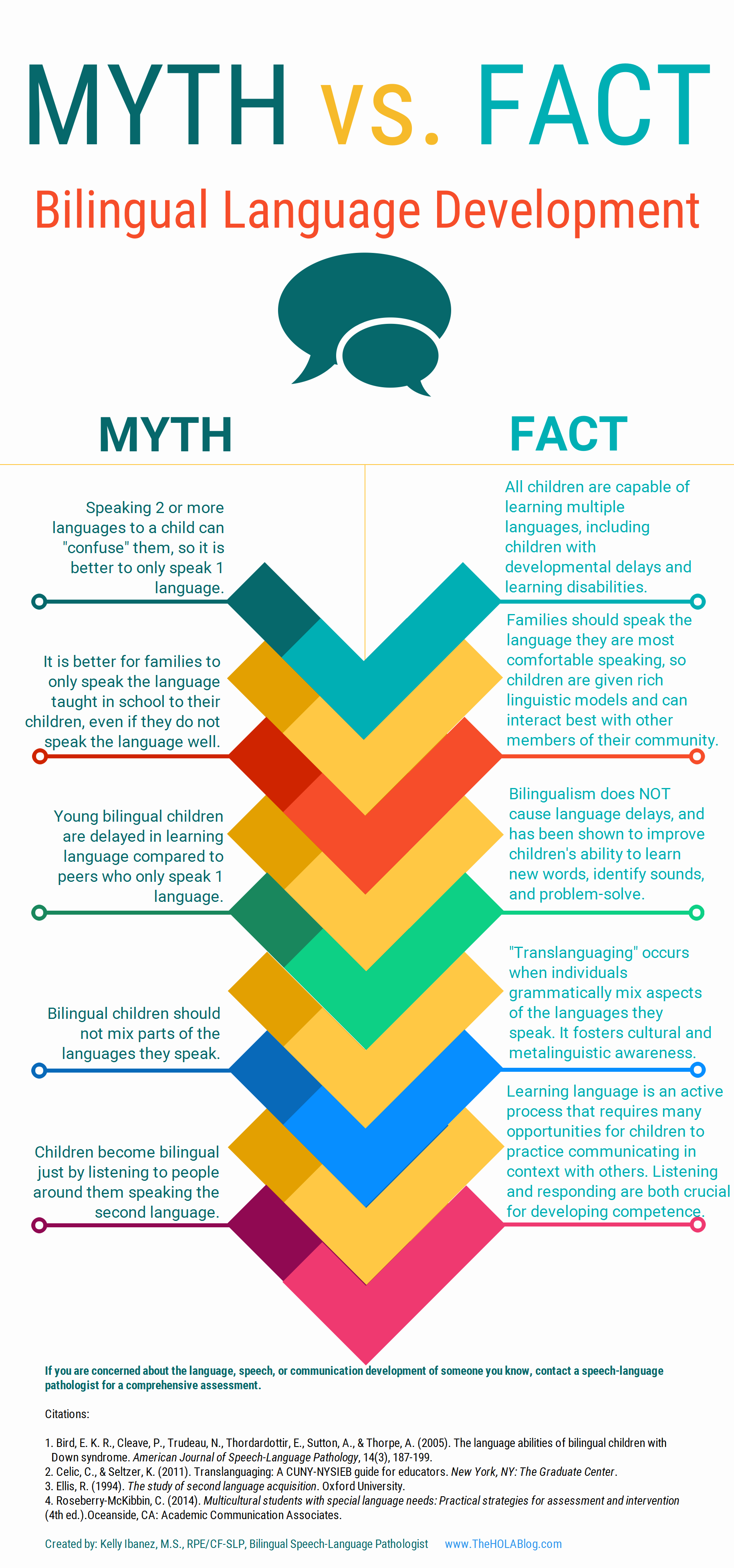

Let’s start with an excellent free infographic entitled from the Hola Blog “Myth vs. Fact: Bilingual Language Development” which was created by Kelly Ibanez, MS CCC-SLP to help dispel bilingual myths and encourage practices that promote multilingualism. Clinicians can download it and refer to it themselves, share it with other health and/or educational professionals as well as show it to parents of their clients.

Let’s start with an excellent free infographic entitled from the Hola Blog “Myth vs. Fact: Bilingual Language Development” which was created by Kelly Ibanez, MS CCC-SLP to help dispel bilingual myths and encourage practices that promote multilingualism. Clinicians can download it and refer to it themselves, share it with other health and/or educational professionals as well as show it to parents of their clients.

Let us now move on to the typical phonological development of English speaking children. After all, in order to compare other languages to English, SLPs need to be well versed in the acquisition of speech sounds in the English language. Children’s speech acquisition, developed by Sharynne McLeod, Ph.D., of Charles Sturt University, is one such resource. It contains a compilation of data on typical speech development for English speaking children, which is organized according to children’s ages to reflect a typical developmental sequence.

Next up, is a great archive which contains phonetic inventories of the various language spoken around the world for contrastive analysis purposes. The same website also contains a speech accent archive. Native and non-native speakers of English were recorded reading the same English paragraph for teaching and research purposes. It is meant to be used by professionals who are interested in comparing the accents of different English speakers.

Next up, is a great archive which contains phonetic inventories of the various language spoken around the world for contrastive analysis purposes. The same website also contains a speech accent archive. Native and non-native speakers of English were recorded reading the same English paragraph for teaching and research purposes. It is meant to be used by professionals who are interested in comparing the accents of different English speakers.

![]() Now let’s talk about one of my favorite websites, MULTILINGUAL CHILDREN’S SPEECH, also developed by Dr. Mcleod of Charles Stuart University. It contains an AMAZING plethora of resources on bilingual speech development and assessment. To illustrate, its Speech Acquisition Data includes A list of over 200 speech acquisition studies. It also contains a HUGE archive on Speech Assessments in NUMEROUS LANGUAGES as well as select assessment reviews. Finally, the website also lists in detail how aspects of speech (e.g., consonants, vowels, syllables, tones) differ between languages.

Now let’s talk about one of my favorite websites, MULTILINGUAL CHILDREN’S SPEECH, also developed by Dr. Mcleod of Charles Stuart University. It contains an AMAZING plethora of resources on bilingual speech development and assessment. To illustrate, its Speech Acquisition Data includes A list of over 200 speech acquisition studies. It also contains a HUGE archive on Speech Assessments in NUMEROUS LANGUAGES as well as select assessment reviews. Finally, the website also lists in detail how aspects of speech (e.g., consonants, vowels, syllables, tones) differ between languages.

The Leader’s Project Website is another highly informative source of FREE information on bilingual assessments, intervention, and FREE CEUS.

Now, I’d like to list some resources regarding language transfer errors.

This chart from Cengage Learning contains a nice, concise Language Guide to Transfer Errors. While it is aimed at multilingual/ESL writers, the information contained on the site is highly applicable to multilingual speakers as well.

You can also find a bonus transfer chart HERE. It contains information on specific structures such as articles, nouns, verbs, pronouns, adverbs, adjectives, word order, questions, commands, and negatives on pages 1-6 and phonemes on pages 7-8.

A final bonus chart entitled: Teacher’s Resource Guide of Language Transfer Issues for English Language Learners containing information on grammar and phonics for 10 different languages can be found HERE.

Similarly, this 16-page handout: Language Transfers: The Interaction Between English and Students’ Primary Languages also contains information on phonics and grammar transfers for Spanish, Cantonese, Vietnamese, Hmong Korean, and Khmer languages.

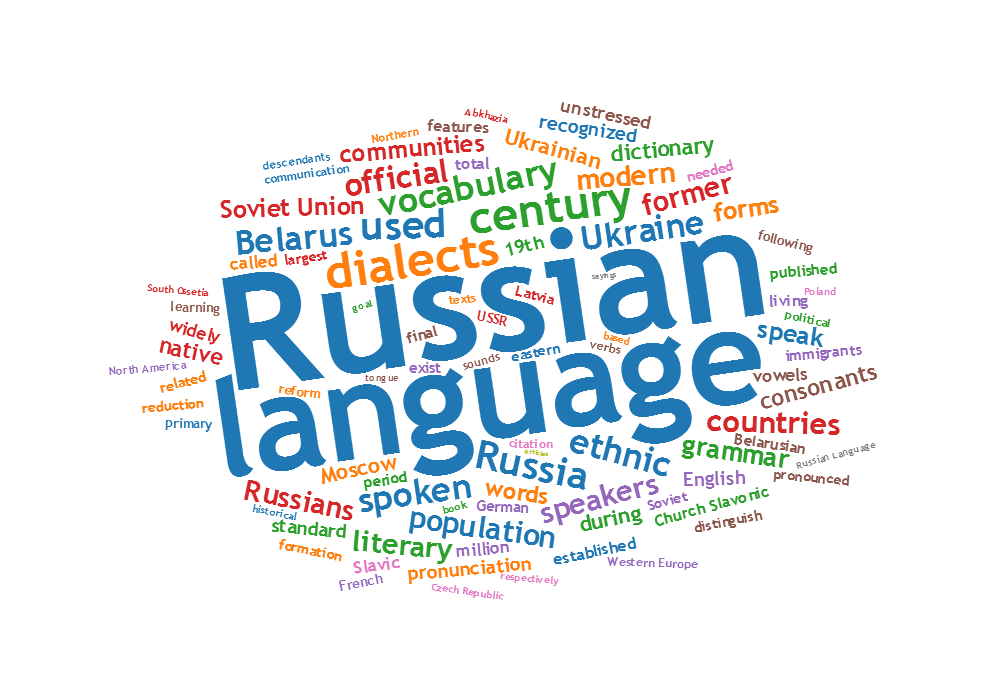

For SLPs working with Russian-speaking children the following links pertinent to assessment, intervention and language transference may be helpful:

For SLPs working with Russian-speaking children the following links pertinent to assessment, intervention and language transference may be helpful:

To determine information about the children’s language development and language environment, in both their first and second language, visit the CHESL Centre website for The Alberta Language Development Questionnaire and The Alberta Language Environment Questionnaire

There you have it! FREE bilingual/multicultural SLP resources compiled for you conveniently in one place. And since there are much more FREE GEMS online, I’d love it if you guys contributed to and expanded this modest list by posting links and title descriptions in the comments section below for others to benefit from!

Together we can deliver the most up to date evidence-based assessment and intervention to bilingual and multicultural students that we serve! Click HERE to check out the FREE Resources in the SLPs for Evidence-Based Practice Group

Helpful Bilingual Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

In my last post, I described how I use obscurely worded newspaper headlines to improve my students’ interpretation of ambiguous and figurative language. Today, I wanted to further delve into this topic by describing the utility of interpreting music lyrics for language therapy purposes. I really like using music lyrics for language treatment purposes. Not only do my students and I get to listen to really cool music, but we also get an opportunity to define a variety of literary devices (e.g., hyperboles, similes, metaphors, etc.) as well as identify them and interpret their meaning in music lyrics. Continue reading What are They Trying To Say? Interpreting Music Lyrics for Figurative Language Acquisition Purposes

In my last post, I described how I use obscurely worded newspaper headlines to improve my students’ interpretation of ambiguous and figurative language. Today, I wanted to further delve into this topic by describing the utility of interpreting music lyrics for language therapy purposes. I really like using music lyrics for language treatment purposes. Not only do my students and I get to listen to really cool music, but we also get an opportunity to define a variety of literary devices (e.g., hyperboles, similes, metaphors, etc.) as well as identify them and interpret their meaning in music lyrics. Continue reading What are They Trying To Say? Interpreting Music Lyrics for Figurative Language Acquisition Purposes

With the passing of dyslexia laws in the state of New Jersey in 2014, there has been an increased focus on reading disabilities and dyslexia particularly in the area of effective assessment and remediation. More and more parents and health related professionals are looking to understand the components of effective dyslexia testing and who is qualified to perform it. So I decided to write a multi-part series regarding the components of comprehensive dyslexia testing in order to assist parents and professionals to better understand the steps of the testing process.

With the passing of dyslexia laws in the state of New Jersey in 2014, there has been an increased focus on reading disabilities and dyslexia particularly in the area of effective assessment and remediation. More and more parents and health related professionals are looking to understand the components of effective dyslexia testing and who is qualified to perform it. So I decided to write a multi-part series regarding the components of comprehensive dyslexia testing in order to assist parents and professionals to better understand the steps of the testing process.

In this particular post I would like to accomplish two things: dispel several common myths regarding dyslexia testing as well as discuss the first step of SLP based testing which is a language assessment.

Myth 1: Dyslexia can be diagnosed based on a single test!

DYSLEXIA CANNOT BE CONFIRMED BY THE ADMINISTRATION OF ONE SPECIFIC TEST. A comprehensive battery of tests from multiple professionals including neuropsychologists, psychologists, learning specialists, speech-language pathologists and even occupational therapists needs to actually be administered in order to confirm the presence of reading based disabilities.

Myth 2: A doctor can diagnose dyslexia!

A doctor does not have adequate training to diagnose learning disabilities, the same way as a doctor cannot diagnose speech and language problems. Both lie squarely outside of their scope of practice! A doctor can listen to parental concerns and suggest an appropriate plan of action (recommend relevant assessments) but they couldn’t possibly diagnose dyslexia which is made on the basis of team assessments.

Myth 3: Speech Pathologists cannot perform dyslexia testing!

SPEECH-LANGUAGE PATHOLOGISTS TRAINED IN IDENTIFICATION OF READING AND WRITING DISORDERS ARE FULLY QUALIFIED TO PERFORM SIGNIFICANT PORTIONS OF DYSLEXIA BATTERY.

So what are the dyslexia battery components?

Prior to initiating an actual face to face assessment with the child, we need to take down a thorough case history (example HERE) in order to determine any pre-existing risk factors. Dyslexia risk factors may include (but are not limited to):

After that, we need to perform language testing to determine whether the child presents with any deficits in that area. Please note that while children with language impairments are at significant risk for dyslexia not all children with dyslexia present with language impairments. In other words, the child may be cleared by language testing but still present with significant reading disability, which is why comprehensive language testing is only the first step in the dyslexia assessment battery.

LANGUAGE TESTING

LANGUAGE TESTING

Here we are looking to assess the child’s listening comprehension. processing skills, and verbal expression in the form of conversational and narrative competencies. Oral language is the prerequisite to reading and writing. So a single vocabulary test, a grammar completion task, or even a sentence formulation activity is simply not going to count as a part of a comprehensive assessment.

In children without obvious linguistic deficits such as limited vocabulary, difficulty following directions, or grammatical/syntactic errors (which of course you’ll need to test) I like to use the following tasks, which are sensitive to language impairment:

Listening Comprehension (with a verbal response component)

Semantic Flexibility

Narrative Production:

Usually I don’t like to use any standardized testing for assessment of this skill but use the parameters from the materials I created myself based on existing narrative research (click HERE).

Social Pragmatic Language

Not sure what type of linguistic deficits your student is displaying? Grab a relevant checklist and ask the student’s teacher and parent fill it out (click HERE to see types of available checklists)

So there you have it! The first installment on comprehensive dyslexia testing is complete.

READ part II which discusses components of Phonological Awareness and Word Fluency testing HERE.

Read part III of this series which discusses components of Reading Fluency and Reading Comprehension testing HERE.

Those of you who have previously read my blog know that I rarely use children’s games to address language goals. However, over the summer I have been working on improving executive function abilities (EFs) of some of the language impaired students on my caseload. As such, I found select children’s games to be highly beneficial for improving language-based executive function abilities.

Those of you who have previously read my blog know that I rarely use children’s games to address language goals. However, over the summer I have been working on improving executive function abilities (EFs) of some of the language impaired students on my caseload. As such, I found select children’s games to be highly beneficial for improving language-based executive function abilities.

For those of you who are only vaguely familiar with this concept, executive functions are higher level cognitive processes involved in the inhibition of thought, action, and emotion, which located in the prefrontal cortex of the frontal lobe of the brain. The development of executive functions begins in early infancy; but it can be easily disrupted by a number of adverse environmental and organic experiences (e.g., psychosocial deprivation, trauma). Furthermore, research in this area indicates that the children with language impairments present with executive function weaknesses which require remediation.

EF components include working memory, inhibitory control, planning, and set-shifting.

Simply put, EFs contribute to the child’s ability to sustain attention, ignore distractions, and succeed in academic settings. By now some of you must be wondering: “So what does Hedbanz have to do with any of it?”

Well, Hedbanz is a quick-paced multiplayer (2-6 people) game of “What Am I?” for children ages 7 and up. Players get 3 chips and wear a “picture card” in their headband. They need to ask questions in rapid succession to figure out what they are. “Am I fruit?” “Am I a dessert?” “Am I sports equipment?” When they figure it out, they get rid of a chip. The first player to get rid of all three chips wins.

The game sounds deceptively simple. Yet if any SLPs or parents have ever played that game with their language impaired students/children as they would be quick to note how extraordinarily difficult it is for the children to figure out what their card is. Interestingly, in my clinical experience, I’ve noticed that it’s not just moderately language impaired children who present with difficulty playing this game. Even my bright, average intelligence teens, who have passed vocabulary and semantic flexibility testing (such as the WORD Test 2-Adolescent or the Vocabulary Awareness subtest of the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy ) significantly struggle with their language organization when playing this game.

So what makes Hedbanz so challenging for language impaired students? Primarily, it’s the involvement and coordination of the multiple executive functions during the game. In order to play Hedbanz effectively and effortlessly, the following EF involvement is needed:

Consequently, all of the above executive functions can be addressed via language-based goals. However, before I cover that, I’d like to review some of my session procedures first.

Typically, long before game initiation, I use the cards from the game to prep the students by teaching them how to categorize and classify presented information so they effectively and efficiently play the game.

Rather than using the “tip cards”, I explain to the students how to categorize information effectively.

Rather than using the “tip cards”, I explain to the students how to categorize information effectively.

This, in turn, becomes a great opportunity for teaching students relevant vocabulary words, which can be extended far beyond playing the game.

I begin the session by explaining to the students that pretty much everything can be roughly divided into two categories animate (living) or inanimate (nonliving) things. I explain that humans, animals, as well as plants belong to the category of living things, while everything else belongs to the category of inanimate objects. I further divide the category of inanimate things into naturally existing and man-made items. I explain to the students that the naturally existing category includes bodies of water, landmarks, as well as things in space (moon, stars, sky, sun, etc.). In contrast, things constructed in factories or made by people would be example of man-made objects (e.g., building, aircraft, etc.)

When I’m confident that the students understand my general explanations, we move on to discuss further refinement of these broad categories. If a student determines that their card belongs to the category of living things, we discuss how from there the student can further determine whether they are an animal, a plant, or a human. If a student determined that their card belongs to the animal category, we discuss how we can narrow down the options of figuring out what animal is depicted on their card by asking questions regarding their habitat (“Am I a jungle animal?”), and classification (“Am I a reptile?”). From there, discussion of attributes prominently comes into play. We discuss shapes, sizes, colors, accessories, etc., until the student is able to confidently figure out which animal is depicted on their card.

In contrast, if the student’s card belongs to the inanimate category of man-made objects, we further subcategorize the information by the object’s location (“Am I found outside or inside?”; “Am I found in ___ room of the house?”, etc.), utility (“Can I be used for ___?”), as well as attributes (e.g., size, shape, color, etc.)

Thus, in addition to improving the students’ semantic flexibility skills (production of definitions, synonyms, attributes, etc.) the game teaches the students to organize and compartmentalize information in order to effectively and efficiently arrive at a conclusion in the most time expedient fashion.

Now, we are ready to discuss what type of EF language-based goals, SLPs can target by simply playing this game.

1. Initiation: Student will initiate questioning during an activity in __ number of instances per 30-minute session given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

2. Planning: Given a specific routine, student will verbally state the order of steps needed to complete it with __% accuracy given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

3. Working Memory: Student will repeat clinician provided verbal instructions pertaining to the presented activity, prior to its initiation, with 80% accuracy given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

4. Flexible Thinking: Following a training by the clinician, student will generate at least __ questions needed for task completion (e.g., winning the game) with __% accuracy given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

5. Organization: Student will use predetermined written/visual cues during an activity to assist self with organization of information (e.g., questions to ask) with __% accuracy given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

6. Impulse Control: During the presented activity the student will curb blurting out inappropriate responses (by silently counting to 3 prior to providing his response) in __ number of instances per 30 minute session given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

7. Emotional Control: When upset, student will verbalize his/her frustration (vs. behavioral activing out) in __ number of instances per 30 minute session given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

8. Self-Monitoring: Following the completion of an activity (e.g., game) student will provide insight into own strengths and weaknesses during the activity (recap) by verbally naming the instances in which s/he did well, and instances in which s/he struggled with __% accuracy given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

There you have it. This one simple game doesn’t just target a plethora of typical expressive language goals. It can effectively target and improve language-based executive function goals as well. Considering the fact that it sells for approximately $12 on Amazon.com, that’s a pretty useful therapy material to have in one’s clinical tool repertoire. For fancier versions, clinicians can use “Jeepers Peepers” photo card sets sold by Super Duper Inc. Strapped for cash, due to highly limited budget? You can find plenty of free materials online if you simply input “Hedbanz cards” in your search query on Google. So have a little fun in therapy, while your students learn something valuable in the process and play Hedbanz today!

Related Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

Having a solid vocabulary knowledge is key to academic success. Vocabulary is the building block of language. It allows us to create complex sentences, tell elaborate stories as well as write great essays. Having limited vocabulary is primary indicator of language learning disability, which in turn blocks students from obtaining critical literacy skills necessary for reading, writing, and spelling. “Indeed, one of the , most enduring findings in reading research is the extent to which students’ vocabulary knowledge relates to their reading comprehension” (Osborn & Hiebert, 2004)

Having a solid vocabulary knowledge is key to academic success. Vocabulary is the building block of language. It allows us to create complex sentences, tell elaborate stories as well as write great essays. Having limited vocabulary is primary indicator of language learning disability, which in turn blocks students from obtaining critical literacy skills necessary for reading, writing, and spelling. “Indeed, one of the , most enduring findings in reading research is the extent to which students’ vocabulary knowledge relates to their reading comprehension” (Osborn & Hiebert, 2004)

Teachers and SLPs frequently inquire regarding effective vocabulary instruction methods for children with learning disabilities. However, what some researchers have found when they set out to “examine how oral vocabulary instruction was enacted in kindergarten” was truly alarming.

In September 2014, Wright and Neuman, analyzed about 660 hours of observations over a course of 4 days (12 hours) in 55 classrooms in a range of socio-economic status schools.

They found that teachers explained word meanings during “teachable moments” in the context of other instruction.

They also found that teachers:

They also found an economic status discrepancy, namely:

Teachers serving in economically advantaged schools explained words more often and were more likely to address sophisticated words than teachers serving in economically disadvantaged schools.

They concluded that “these results suggest that the current state of instruction may be CONTRIBUTING to rather than ameliorating vocabulary gaps by socioeconomic status.”

Similar findings were reported by other scholars in the field who noted that “teachers with many struggling children often significantly reduce the quality of their own vocabulary unconsciously to ensure understanding.” So they “reduce the complexity of their vocabulary drastically.” “For many children the teacher is the highest vocabulary example in their life. It’s sort of like having a buffet table but removing everything except a bowl of peanuts-that’s all you get“. (Excerpts from Anita Archer’s Interview with Advance for SLPs)

It is important to note that vocabulary gains are affected by socioeconomic status as well as maternal education level. Thus, children whose family incomes are at or below the poverty level fare much more poorly in the area of vocabulary acquisition than middle class children. Furthermore, Becker (2011) found that children of higher educated parents can improve their vocabulary more strongly than children whose parents have a lower educational level.

Limitations of Poor Readers:

Poor readers often lack adequate vocabulary to get meaning from what they read. To them, reading is difficult and tedious, and they are unable (and often unwilling) to do the large amount of reading they must do if they are to encounter unknown words often enough to learn them.

Matthew Effect, “rich get richer, poor get poorer”, or interactions with the environment exaggerate individual differences over time. Good readers read more, become even better readers, and learn more words. Poor readers read less, become poorer readers, and learn fewer words. The vocabulary problems of students who enter school with poorer limited vocabularies only exacerbate over time.

However, even further exacerbating the issue is that students from low SES households have limited access to books. 61% of low-income families have NO BOOKS at all in their homes for their children (Reading Literacy in the United States: Findings from the IEA Reading Literacy Study, 1996.) In some under-resourced communities, there is ONLY 1 book for every 300 children. Neuman, S., & Dickinson, D. (Eds.). (2006) Handbook of Early Literacy Research (Vol. 2). In contrast, the average middle class child has 13+ books in the home.

The above discrepancy can be effectively addressed by holding book drives to raise books for under privileged students and their siblings. Instructions for successful book drives HERE.

So what are effective methods of vocabulary instruction for children with language impairments?

According to (NRP, 2000) a good way for students to learn vocabulary directly is to explicitly teach them individual words and word-learning strategies .

For children with low initial vocabularies, approaches that teach word meanings as part of a semantic field are found to be especially effective (Marmolejo, 1991).

Many vocabulary scholars (Archer, 2011; Biemiller, 2004; Gunning 2004, etc.) agree on a number of select instructional strategies which include:

Response to Intervention: Improving Vocabulary Outcomes

For students with low vocabularies, to attain the same level of academic achievement as their peers on academic coursework of language arts, reading, and written composition, targeted Tier II intervention may be needed.

Tier II words are those for which children have an understanding of the underlying concepts, are useful across a variety of settings and can be used instructionally in a variety of ways

According to Beck et al 2002, Tier II words should be the primary focus of vocabulary instruction, as they would make the most significant impact on a child’s spoken and written expressive capabilities.

Tier II vocabulary words

According to Judy Montgomery “You can never select the wrong words to teach.”

Vocabulary Selection Tips:

Examples of Spring Related Vocabulary

Adjectives:

Nouns:

Verbs

Idiomatic Expressions:

Creating an Effective Vocabulary Intervention Packets and Materials

Sample Activity Suggestions:

Intervention Technique Suggestions:

1.Read vocabulary words in context embedded in relevant short texts

2.Teach individual vocabulary words directly to comprehend classroom-specific texts (definitions)

3.Provide multiple exposures of vocabulary words in multiple contexts, (synonyms, antonyms, multiple meaning words, etc.)

4.Maximize multisensory intervention when learning vocabulary to maximize gains (visual, auditory, tactile, etc.)

5.Use multiple instructional methods for a range of vocabulary learning tasks and outcomes (read it, spell it, write it in a sentence, practice with a friend, etc.)

6.Use morphological awareness instruction (post to follow)

Conclusion:

Having the right tools for the job is just a small first step in the right direction of creating a vocabulary-rich environment even for the most disadvantaged learners. So Happy Speeching!

Helpful Smart Speech Resources:

Recently, I’ve published an article in SIG 16 Perspectives on School Based Issues discussing the importance of social communication assessments of school aged children 2-18 years of age. Below I would like to summarize article highlights.

Recently, I’ve published an article in SIG 16 Perspectives on School Based Issues discussing the importance of social communication assessments of school aged children 2-18 years of age. Below I would like to summarize article highlights.

First, I summarize the effect of social communication on academic abilities and review the notion of the “academic impact”. Then, I go over important changes in terminology and definitions as well as explain the “anatomy of social communication”.

Next I suggest a sample social communication skill hierarchy to adequately determine assessment needs (assess only those abilities suspected of deficits and exclude the skills the student has already mastered).

After that I go over pre-assessment considerations as well as review standardized testing and its limitations from 3-18 years of age.

Finally I review a host of informal social communication procedures and address their utility.

What is the away message?

When evaluating social communication, clinicians need to use multiple assessment tasks to create a balanced assessment. We need to chose testing instruments that will help us formulate clear goals. We also need to add descriptive portions to our reports in order to “personalize” the student’s deficit areas. Our assessments need to be functional and meaningful for the student. This means determining the student’s strengths and not just weaknesses as a starting point of intervention initiation.

Is this an article which you might find interesting? If so, you can access full article HERE free of charge.

Helpful Smart Speech Resources Related to Assessment and Treatment of Social Communication

Scenario: John is a bright 11 year old boy who was adopted at the age of 3 from Russia by American parents. John’s favorite subject is math, he is good at sports but his most dreaded class is language arts. John has trouble understanding abstract information or summarizing what he has seen, heard or read. John’s grades are steadily slipping and his reading comprehension is below grade level. He has trouble retelling stories and his answers often raise more questions due to being very confusing and difficult to follow. John has trouble maintaining friendships with kids his age, who consider him too immature and feel like he frequently “misses the point” due to his inability to appropriately join play activities and discussions, understand non-verbal body language, maintain conversations on age-level topics, or engage in perspective taking (understand other people’s ideas, feelings, and thoughts). John had not received speech language services immediately post adoption despite exhibiting a severe speech and language delay at the time of adoption. The parents were told that “he’ll catch up quickly”, and he did, or so it seemed, at the time. John is undeniably bright yet with each day he struggles just a little bit more with understanding those around him and getting his point across. John’s scores were within normal limits on typical speech and language tests administered at his school, so he did not qualify for school based speech language therapy. Yet John clearly needs help.

John’s case is by no means unique. Numerous adopted children begin to experience similar difficulties; years post adoption, despite seemingly appropriate early social and academic development. What has many parents bewildered is that often times these difficulties are not glaringly pronounced in the early grades, which leads to delayed referral and lack of appropriate intervention for prolonged period of time.

The name for John’s difficulty is pragmatic language impairment, a diagnosis that has been the subject of numerous research debates since it was originally proposed in 1983 by Rapin and Allen.

So what is pragmatic language impairment and how exactly does it impact the child’s social and academic language abilities?

In 1983, Rapin and Allen proposed a classification of children with developmental language disorders. As part of this classification they described a syndrome of language impairment which they termed ‘semantic–pragmatic deficit syndrome’. Children with this disorder were described as being overly verbose, having poor turn–taking skills, poor discourse and narrative skills as well as having difficulty with topic initiation, maintenance and termination. Over the years the diagnostic label for this disorder has changed several times, until it received its current name “pragmatic language impairment” (Bishop, 2000).

Pragmatic language ability involves the ability to appropriately use language (e.g., persuade, request, inform, reject), change language (e.g., talk differently to different audiences, provide background information to unfamiliar listeners, speak differently in different settings, etc) as well as follow conversational rules (e.g., take turns, introduce topics, rephrase sentences, maintain appropriate physical distance during conversational exchanges, use facial expressions and eye contact, etc) all of which culminate into the child’s general ability to appropriately interact with others in a variety of settings.

For most typically developing children, the above comes naturally. However, for children with pragmatic language impairment appropriate social interactions are not easy. Children with pragmatic language impairment often misinterpret social cues, make inappropriate or off-topic comments during conversations, tell stories in a disorganized way, have trouble socially interacting with peers, have difficulty making and keeping friends, have difficulty understanding why they are being rejected by peers, and are at increased risk for bullying.

So why do adopted children experience social pragmatic language deficits many years post adoption?

Well for one, many internationally adopted children are at high risk for developmental delay because of their exposure to institutional environments. Children in institutional care often experience neglect, lack of language stimulation, lack of appropriate play experiences, lack of enriched community activities, as well as inadequate learning settings all of which has long lasting negative impact on their language development including the development of their pragmatic language skills (especially if they are over 3 years of age). Furthermore, other, often unknown, predisposing factors such as medical, genetic, and family history can also play a negative role in pragmatic language development, since at the time of adoption very little information is known about the child’s birth parents or maternal prenatal care.

Difficulty with detection as well as mistaken diagnoses of pragmatic language impairment

Whereas detecting difficulties with language content and form is relatively straightforward, pragmatic language deficits are more difficult to detect, because pragmatics are dependent on specific contexts and implicit rules. While many children with pragmatic language impairment will present with poor reading comprehension, low vocabulary, and grammar errors (pronoun reversal, tense confusion) in addition to the already described deficits, not all the children with pragmatic language impairment will manifest the above signs. Moreover, while pragmatic language impairment is diagnosed as one of the primary difficulties in children on autistic spectrum, it can manifest on its own without the diagnosis of autism. Furthermore, due to its complicated constellation of symptoms as well as frequent coexistence with other disorders, pragmatic language impairment as a standalone diagnosis is often difficult to establish without the multidisciplinary team involvement (e.g., to rule out associated psychiatric and neurological impairment).

It is also not uncommon for pragmatic language deficits to manifest in children as challenging behaviors (and in severe cases be misdiagnosed due to the fact that internationally adopted children are at increased risk for psychiatric disorders in childhood, adolescence and adulthood). Parents and teachers often complain that these children tend to “ignore” presented directions, follow their own agenda, and frequently “act out inappropriately”. Unfortunately, since children with pragmatic language impairment rely on literal communication, they tend to understand and carry out concrete instructions and tasks versus understanding indirect requests which contain abstract information. Additionally, since perspective taking abilities are undeveloped in these children, they often fail to understand and as a result ignore or disregard other people’s feelings, ideas, and thoughts, which may further contribute to parents’ and teachers’ beliefs that they are deliberately misbehaving.

Due to difficulties with detection, pragmatic language deficits can persist undetected for several years until they are appropriately diagnosed. What may further complicate detection is that a certain number of children with pragmatic language deficits will perform within the normal range on typical speech and language testing. As a result, unless a specific battery of speech language tests is administered that explicitly targets the identification of pragmatic language deficits, some of these children may be denied speech and language services on the grounds that their total language testing score was too high to qualify them for intervention.

How to initiate an appropriate referral process if you suspect that your school age child has pragmatic language deficits?

When a child is presenting with a number of above described symptoms, it is recommended that a medical professional such as a neurologist or a psychologist be consulted in order to rule out other more serious diagnoses. Then, the speech language pathologist can perform testing in order to confirm the presence of pragmatic language impairment as well as determine whether any other linguistically based deficits coexist with it. Furthermore, even in cases when the pragmatic language impairment is a secondary diagnosis (e.g. Autism) the speech language pathologist will still need to be involved in order to appropriately address the social linguistic component of this deficit.

To obtain appropriate speech and language testing in a school setting, the first step that parents can take is to consult with the classroom teacher. For the school age child (including preschool and kindergarten) the classroom teacher can be the best parental ally. After all both parents and teachers know the children quite well and can therefore take into account their behavior and functioning in a variety of social and academic contexts. Once the list of difficulties and inappropriate behaviors has been compiled, and both parties agree that the “red flags” merit further attention, the next step is to involve the school speech language pathologist (make a referral) to confirm the presence and/or severity of the impairment via speech language testing.

When attempting to confirm/rule out pragmatic language impairment, the speech language pathologist has the option of using a combination of formal and informal assessments including parental questionnaires, discourse and narrative analyses as well as observation checklists.

Below is the list of select formal and informal speech language assessment instruments which are sensitive to detection of pragmatic language impairment in children as young as 4-5 years of age.

1. Children’s Communication Checklist-2 (CCC–2) (Available: Pearson Publication)

2. Test of Narrative Development (TNL) (Available: Linguisystems Publication)

3. Test of Language Competence Expanded Edition (TLC-E) (Available: Pearson Publication)

4. Test of Pragmatic Language-2 (TOPL-2) (Available: Linguisystems Publication)

5. Social Emotional Evaluation (SEE) (Available: Super Duper Publication)

6. Dynamic Informal Social Thinking Assessment (www.socialthinking.com)

7. Social Language Development Test -Elementary (SLDT-E) (Available: Linguisystems Publication)

8. Social Language Development Test -Adolescent (SLDT-A) (Available: Linguisystems Publication)

It is also very important to note that several formal and informal instruments and analyses need to be administered/performed in order to create a complete diagnostic picture of the child’s deficits.

When to seek private pragmatic language evaluation and therapy services?

Unfortunately, the process of obtaining appropriate social pragmatic assessment in a school setting is often fraught with numerous difficulties. For one, due to financial constraints, not all school districts possess the appropriate, up to date pragmatic language testing instruments.

Another issue is the lack of time. To administer comprehensive assessment which involves 2-3 different assessment instruments, an adequate amount of time (e.g., 2+ hours) is needed in order to create the most comprehensive pragmatic profile for the child. School based speech language pathologists often lack this valuable commodity due to increased case load size (often seeing between 45 to 60 students per week), which leaves them with very limited time for testing.

Further complicating the issue are the special education qualification rules, which are different not just from state to state but in some cases from one school district to the next within the same state. Some school districts strictly stipulate that the child’s performance on testing must be 1.5-2 standard deviations below the normal limits in order to qualify for therapy services.

But what if the therapist is not in possession of any formal assessment instruments and can only do informal assessment?

And what happens to the child who is “not impaired enough” (e.g., 1 SD vs. 1.5 SD)?

Consequently, in recent years more and more parents are opting for private pragmatic language assessments and therapy for their children.

Certainly, there are numerous advantages for going via the private route. For one, parents are directly involved and directly influence the quality of care their children receive.

One advantage to private therapy is that parents can request to be present during the evaluation and therapy sessions. As such, not only do the parents get to understand the extent of the child’s impairment but they also learn valuable techniques and strategies they can utilize in home setting to facilitate carryover and skill generalization (how to ask questions, provide choices, etc).

Another advantage is the provision of individual therapy services in contrast to school based services which are generally attended by groups as large as 4-5 children per session. Here, some might disagree and state that isn’t the point of pragmatic therapy is for the child to practice his/her social skills with other children?

Absolutely! However, before a skill can be generalized it needs to be taught! Most children with pragmatic language impairment initially require individual sessions, in some of which it may be necessary to use drill work to teach a specific skill. Once the necessary skills are taught, only then can children be placed into social groups where they can practice generalizing their skills. Moreover, many of these children greatly benefit from being in group or play settings with typical peers and/or sibling tutors who may facilitate the generalization of the desired skill more naturally, all of which can be arranged within private therapy settings.

Yet another advantage to obtaining private therapy services is that there are some private clinics which are almost exclusively devoted to teaching social pragmatic communication and which offer a variety of therapeutic services including individual therapy, group therapy and even summer camps that target the improvement of pragmatic language and social communication skills.

The flexibility offered by private therapy is also important if a parent is seeking a specific social skills curriculum for their child (e.g., “Socially Speaking”) or if they are interested in social skill training that is based on the methods of specific researchers/authors (e.g., Michelle Garcia Winner MACCC-SLP; Dr. Jed Baker PhD, etc), which may not be offered by their child’s school.

There are many routes open for parents to pursue when it comes to their child’s pragmatic language assessment and intervention. However, the first step in that process is parental education!

To learn more about pragmatic language impairment please visit the ASHA website at www.asha.org and type in your query in the search window located in the upper right corner of the website. To find a professional specializing in assessment and treatment of pragmatic language disorders in your area please visit http://asha.org/proserv/.

References

Adams, C. (2001). “Clinical diagnostic and intervention studies of children with semantic-pragmatic language disorder.” International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 36(3): 289-305.

Bishop, D. V. (1989). “Autism, Asperger’s syndrome and semantic-pragmatic disorder: Where are the boundaries?” British Journal of Disorders of Communication 24(2): 107-121.

Bishop, D. V. M. and G. Baird (2001). “Parent and teacher report of pragmatic aspects of communication: Use of the Children’s Communication Checklist in a clinical setting.” Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 43(12): 809-818.

Botting, N., & Conti-Ramsden, G. (1999). Pragmatic language impairment without autism: The children in question. Autism, 3, 371–396.[

Brackenbury, T., & Pye, C. (2005). Semantic deficits in children with language impairments: Issues for clinical assessment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 36, 5–16.

Burgess, S., & Turkstra, L. S. (2006). Social skills intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorders: A review of the experimental evidence. EBP Briefs, 1(4), 1–21.

Camarata, S., M., and T. Gibson (1999). “Pragmatic Language Deficits in Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).” Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities 5: 207-214.

Ketelaars, M. P., Cuperus, J. M., Jansonius, K., & Verhoeven, L. (2009). Pragmatic language impairment and associated behavioural problems. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 45, 204–214.

Ketelaars, M. P., Cuperus, J. M., Van Daal, J., Jansonius, K., & Verhoeven, L. (2009). Screening for pragmatic language impairment: The potential of the Children’s Communication Checklist. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30, 952–960.

Miniscalco, C., Hagberg, B., Kadesjö, B., Westerlund, M., & Gillberg, C. (2007). Narrative skills, cognitive profiles and neuropsychiatric disorders in 7-8-year-old children with late developing language. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 42, 665–681.

Rapin I, Allen D (1983). Developmental language disorders: Nosologic considerations. In U. Kirk (Ed.), Neuropsychology of language, reading, and spelling (pp. 155–184). : Academic Press.