It’s early August, and that means that the start of a new school year is just around the corner. It also means that many newly graduated clinical fellows (as well as SLPs switching their settings) will begin their exciting yet slightly terrifying new jobs working for various school systems around the country. Since I was recently interviewing clinical fellows myself in my setting (an outpatient school located in a psychiatric hospital, run by a university), I decided to write this post in order to assist new graduates, and setting-switching professionals by describing what knowledge and skills are desirable to possess when working in the schools. Continue reading Clinical Fellow (and Setting-Switching SLPs) Survival Guide in the Schools

It’s early August, and that means that the start of a new school year is just around the corner. It also means that many newly graduated clinical fellows (as well as SLPs switching their settings) will begin their exciting yet slightly terrifying new jobs working for various school systems around the country. Since I was recently interviewing clinical fellows myself in my setting (an outpatient school located in a psychiatric hospital, run by a university), I decided to write this post in order to assist new graduates, and setting-switching professionals by describing what knowledge and skills are desirable to possess when working in the schools. Continue reading Clinical Fellow (and Setting-Switching SLPs) Survival Guide in the Schools

Search Results for: http:/www.smartspeechtherapy.com/shop/fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorders-assessment-and-treatment-bundle

Dear School Professionals Please Be Aware of This

I frequently get emails, phone calls, and questions from parents and professionals regarding academic functioning of internationally adopted post institutionalized children. Unfortunately despite the fact that there is a fairly large body of research on this topic there still continue to be numerous misconceptions regarding how these children’s needs should be addressed in academic settings.

Perhaps one of the most serious and damaging misconceptions is that internationally adopted children are bilingual/multicultural children with Limited English Proficiency who need to be treated as ESL speakers. This erroneous belief often leads to denial or mismanagement of appropriate level of services for these children not only with respect to their language processing and verbal expression but also their social pragmatic language abilities.

Even after researchers published a number of articles on this topic, many psychologists, teachers and speech language pathologists still don’t know that internationally adopted children rapidly lose their little birth language literally months post their adoption by English-speaking parents/families. Gindis (2005) found that children adopted between 4-7 years of age lose expressive birth language abilities within 2-3 months and receptive abilities within 3-6 months post- adoption. This process is further expedited in children under 4, whose language is delayed or impaired at the time of adoption (Gindis, 2008). Even school-aged children of 10-12 years of age who were able to read and write in their birth language, rapidly lose their comprehension and expression of birth language within their first year post adoption, if adopted by English-speaking parents who are unable to support their birth language.

So how does this translate into appropriate provision of speech language services you may ask? To begin with, I often see posts on the ASHA forums or in Facebook speech pathology and special education groups seeking assistance with finding interpreters fluent in various exotic languages. However, unless the child is “fresh off the boat” (several months post arrival to US) schools shouldn’t be feverishly trying to locate interpreters to assist with testing in the child’s birth language. They will not be able to obtain any viable results especially if the child had been residing in the United States for several years.

So if the post-institutionalized, internationally adopted child is still struggling with academics several years post adoption, one should not immediately jump to the conclusion that this is an “ESL” issue, but get relevant professionals (e.g., speech pathologists, psychologists) to perform thorough testing in order to determine whether it’s the lack of foundational abilities due to institutionalization which is adversely impacting the child’s academic abilities.

Furthermore, ESL itself is often not applicable as an educational method to internationally adopted children. Here’s why:

Let’s literally take the first definition of ESL which pops-up on Google when you put in a query: “What is ESL?” “English as a Second Language (ESL) is an instructional program for students whose dominant language is not English. The purpose of the program is to increase the English language proficiency of eligible students so they can attain academic standards and achieve success in the classroom.”

Here is our first problem. These students don’t have a dominant language. They are typically adopted by parents who do not speak their birth language and that are unable to support them in their birth language. So upon arrival to US, IA children will typically acquire English via the subtractive model of language acquisition (birth language is replaced and eliminated by English), which is a direct contrast to bilingual children, many of whom learn via the additive model (adding English to the birth language (Gindis, 2005). As a result, of subtractive language acquisition IA children experience very rapid birth language attrition (loss) post-adoption (Gindis, 2003; Glennen, 2009). Thus they will literally undergo what some researchers have called: “second-first language acquisition” (Scott et al., 2011) and their first language will “become completely obsolete as English is learned” (Nelson, 2012, p. 2).

This brings us to our second problem: the question of “eligibility”. Historically, ESL programs have been designed to assist children of immigrant families acquire academic readiness skills. This methodology is based on the fact that skills from first language was ultimately transfer to the second language. However, since post-institutionalized children don’t technically have a “first language” and their home language is English, how could they technically be eligible for ESL services? Furthermore, because of frequent lack of basic foundational skills in the birth language internationally adopted post-institutionalized children will not benefit the same way from ESL instruction the same way bilingual children of immigrant families do. So instead of focusing on these children’s questionable eligibility for ESL services it is important to perform detailed review of their pre-adoption records in order to determine birth language deficits and consider eligibility for speech language services with the emphasis on improving these children’s foundational skills.

Now that we have discussed the issue of ESL services, lets touch upon social pragmatic language abilities of internationally adopted children. Here’s how erroneous beliefs can contribute to mismanagement of appropriate services in this area.

Different cultures have different pragmatic conventions, therefore we are taught to be very careful when labeling certain behaviors of children from other cultures as atypical, just because they are not consistent with the conventions and behaviors of children from the mainstream culture. Here’s a recent example. A mainstream American parent consulted an SLP regarding the inappropriate social pragmatic skills of her teenaged daughter adopted almost a decade ago from Southeast Asia. The SLP was under the impression that some of the child’s deficits were due to multicultural differences and had to do with the customs and traditions of the child’s country of origin. She was considering advising the parent regarding requesting an evaluation by a SLP who spoke the child’s birth language.

Here are two problems with the above scenario. Firstly, any internationally adopted post-institutionalized child who was adopted by American parents who were not part of the culture from which the child was adopted, the child will quickly become acculturated and immersed in the American culture. These children “need functional English for survival”, and thus have a powerful incentive to acquire English (Gindis, 2005; p. 299). consequently, any unusual or atypical behaviors they exhibit in social interactions and in academic setting with other individuals cannot be attributed to customs and traditions of another culture.

Secondly, It is very important to understand that institutionalization and orphanage care have been closely linked to increase in mental health disorders and psychiatric impairments. As a result, internationally adopted children have a high incidence of social pragmatic deficits as compared to non-adopted peers as well as post-institutionalized children adopted at younger ages, (under 3). Given this, if parents present with concerns regarding their internationally adopted post-institutionalized children’s social pragmatic and behavioral functioning it is very important not to jump to erroneous conclusion pertaining to these children’s birth countries but rather preform comprehensive evaluations in order to determine whether these children can be assisted further in the realm of social pragmatic functioning in a variety of settings.

In order to develop a clear picture regarding appropriate service delivery for IA children, school based professionals need to educate themselves regarding the fundamental differences between development and learning trajectories of internationally adopted children and multicultural/bilingual children. Children, who struggle academically, after years of adequate schooling exposure, do not deserve a “wait and see” approach. They should start receiving appropriate intervention as soon as possible (Hough & Kaczmarek, 2011; Scott & Roberts, 2007).

Spotlight on Syndromes: An SLPs Perspective on Down Syndrome

Today’s guest post on genetic syndromes comes from Rachel Nortz, who is contributing a post on the Down Syndrome.

Today’s guest post on genetic syndromes comes from Rachel Nortz, who is contributing a post on the Down Syndrome.

Down Syndrome is a genetic disorder that is characterized by all or part of a third copy of the 21st chromosome. There are three different forms of Down syndrome: trisomy 21, translocation, and mosaicism. Trisomy 21 is the most common form of Down syndrome. This occurs when the 21st chromosome pair does not split properly and the egg or sperm receives a double-dose of the extra chromosome. Translocation (3-4% have this type) is the result of when the extra part of the 21st chromosome becomes attached (translocated) onto another chromosome. Mosaicism is the result of an extra 21st chromosome in only some of the cells and this is the least common type of Down syndrome. Continue reading Spotlight on Syndromes: An SLPs Perspective on Down Syndrome

Language Processing Deficits (LPD) Checklist for School Aged Children

Need a Language Processing Deficits Checklist for School Aged Children

Need a Language Processing Deficits Checklist for School Aged Children

You can find it in my online store HERE

This checklist was created to assist speech-language pathologists (SLPs) with figuring out whether the student presents with language processing deficits which require further follow-up (e.g., screening, comprehensive assessment). The SLP should provide this form to both teacher and caregiver/s to fill out to ensure that the deficit areas are consistent across all settings and people.

Checklist Categories:

- Listening Skills and Short Term Memory

- Verbal Expression

- Emergent Reading/Phonological Awareness

- General Organizational Abilities

- Social-Emotional Functioning

- Behavior

- Supplemental* Caregiver/Teacher Data Collection Form

- Select assessments sensitive to Auditory Processing Deficits

Language Processing Checklist for Preschool Children 3:0-5:11 Years of Age

Children at risk for auditory processing deficits can begin displaying difficulties processing and using language at a very early age (before 3).

Children at risk for auditory processing deficits can begin displaying difficulties processing and using language at a very early age (before 3).

By the time these children reach preschool age (3+ years) they may present with obvious signs and symptoms of language processing deficits, which may require further screening and intervention. Continue reading Language Processing Checklist for Preschool Children 3:0-5:11 Years of Age

Is it a Difference or a Disorder? Free Resources for SLPs Working with Bilingual and Multicultural Children

For bilingual and monolingual SLPs working with bilingual and multicultural children, the question of: “Is it a difference or a disorder?” arises on a daily basis as they attempt to navigate the myriad of difficulties they encounter in their attempts at appropriate diagnosis of speech, language, and literacy disorders.

For bilingual and monolingual SLPs working with bilingual and multicultural children, the question of: “Is it a difference or a disorder?” arises on a daily basis as they attempt to navigate the myriad of difficulties they encounter in their attempts at appropriate diagnosis of speech, language, and literacy disorders.

For that purpose, I’ve recently created a Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children. Its aim is to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) and Teachers in the decision-making process of how to appropriately identify bilingual/multicultural children who present with speech-language delay/deficits (vs. a language difference), for the purpose of initiating a formal speech-language-literacy evaluation. The goal is to ensure that educational professionals are appropriately identifying bilingual children for assessment and service provision due to legitimate speech language deficits/concerns, and are not over-identifying students because they speak multiple languages or because they come from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It is very important to understand that true language impairment in bilingual children will be evident in both languages from early childhood onwards, and thus will adversely affect the learning of both languages.

For that purpose, I’ve recently created a Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children. Its aim is to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) and Teachers in the decision-making process of how to appropriately identify bilingual/multicultural children who present with speech-language delay/deficits (vs. a language difference), for the purpose of initiating a formal speech-language-literacy evaluation. The goal is to ensure that educational professionals are appropriately identifying bilingual children for assessment and service provision due to legitimate speech language deficits/concerns, and are not over-identifying students because they speak multiple languages or because they come from low socioeconomic backgrounds. It is very important to understand that true language impairment in bilingual children will be evident in both languages from early childhood onwards, and thus will adversely affect the learning of both languages.

However, today the aim of today’s post is not on the above product but rather on the FREE free bilingual and multicultural resources available to SLPs online in their quest of differentiating between a language difference from a language disorder in bilingual and multicultural children.

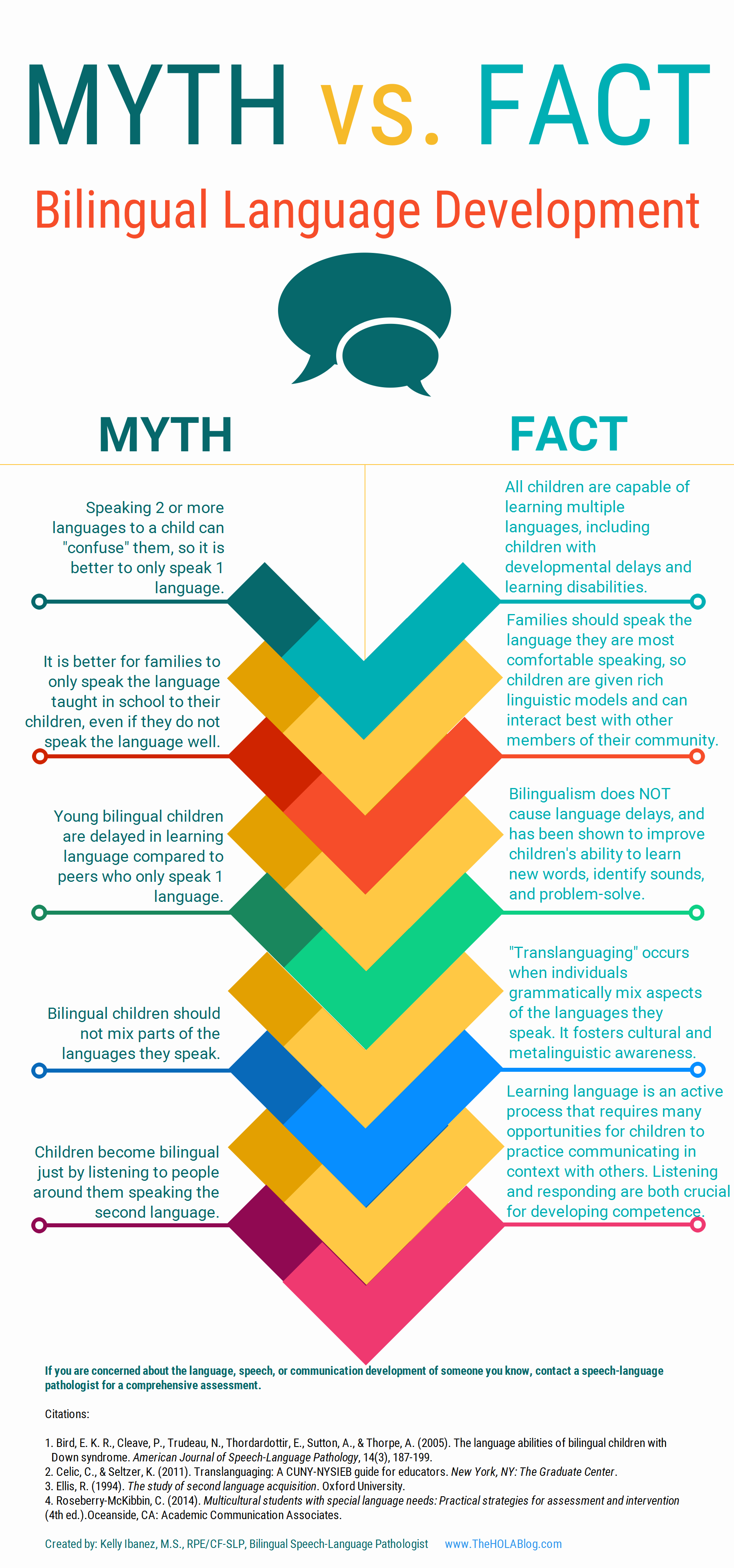

Let’s start with an excellent free infographic entitled from the Hola Blog “Myth vs. Fact: Bilingual Language Development” which was created by Kelly Ibanez, MS CCC-SLP to help dispel bilingual myths and encourage practices that promote multilingualism. Clinicians can download it and refer to it themselves, share it with other health and/or educational professionals as well as show it to parents of their clients.

Let’s start with an excellent free infographic entitled from the Hola Blog “Myth vs. Fact: Bilingual Language Development” which was created by Kelly Ibanez, MS CCC-SLP to help dispel bilingual myths and encourage practices that promote multilingualism. Clinicians can download it and refer to it themselves, share it with other health and/or educational professionals as well as show it to parents of their clients.

Let us now move on to the typical phonological development of English speaking children. After all, in order to compare other languages to English, SLPs need to be well versed in the acquisition of speech sounds in the English language. Children’s speech acquisition, developed by Sharynne McLeod, Ph.D., of Charles Sturt University, is one such resource. It contains a compilation of data on typical speech development for English speaking children, which is organized according to children’s ages to reflect a typical developmental sequence.

Next up, is a great archive which contains phonetic inventories of the various language spoken around the world for contrastive analysis purposes. The same website also contains a speech accent archive. Native and non-native speakers of English were recorded reading the same English paragraph for teaching and research purposes. It is meant to be used by professionals who are interested in comparing the accents of different English speakers.

Next up, is a great archive which contains phonetic inventories of the various language spoken around the world for contrastive analysis purposes. The same website also contains a speech accent archive. Native and non-native speakers of English were recorded reading the same English paragraph for teaching and research purposes. It is meant to be used by professionals who are interested in comparing the accents of different English speakers.

![]() Now let’s talk about one of my favorite websites, MULTILINGUAL CHILDREN’S SPEECH, also developed by Dr. Mcleod of Charles Stuart University. It contains an AMAZING plethora of resources on bilingual speech development and assessment. To illustrate, its Speech Acquisition Data includes A list of over 200 speech acquisition studies. It also contains a HUGE archive on Speech Assessments in NUMEROUS LANGUAGES as well as select assessment reviews. Finally, the website also lists in detail how aspects of speech (e.g., consonants, vowels, syllables, tones) differ between languages.

Now let’s talk about one of my favorite websites, MULTILINGUAL CHILDREN’S SPEECH, also developed by Dr. Mcleod of Charles Stuart University. It contains an AMAZING plethora of resources on bilingual speech development and assessment. To illustrate, its Speech Acquisition Data includes A list of over 200 speech acquisition studies. It also contains a HUGE archive on Speech Assessments in NUMEROUS LANGUAGES as well as select assessment reviews. Finally, the website also lists in detail how aspects of speech (e.g., consonants, vowels, syllables, tones) differ between languages.

The Leader’s Project Website is another highly informative source of FREE information on bilingual assessments, intervention, and FREE CEUS.

Now, I’d like to list some resources regarding language transfer errors.

This chart from Cengage Learning contains a nice, concise Language Guide to Transfer Errors. While it is aimed at multilingual/ESL writers, the information contained on the site is highly applicable to multilingual speakers as well.

You can also find a bonus transfer chart HERE. It contains information on specific structures such as articles, nouns, verbs, pronouns, adverbs, adjectives, word order, questions, commands, and negatives on pages 1-6 and phonemes on pages 7-8.

A final bonus chart entitled: Teacher’s Resource Guide of Language Transfer Issues for English Language Learners containing information on grammar and phonics for 10 different languages can be found HERE.

Similarly, this 16-page handout: Language Transfers: The Interaction Between English and Students’ Primary Languages also contains information on phonics and grammar transfers for Spanish, Cantonese, Vietnamese, Hmong Korean, and Khmer languages.

For SLPs working with Russian-speaking children the following links pertinent to assessment, intervention and language transference may be helpful:

For SLPs working with Russian-speaking children the following links pertinent to assessment, intervention and language transference may be helpful:

- Working with Russian-speaking clients: implications for speech-language assessment

- Strategies in the acquisition of segments and syllables in Russian-speaking children

- Language Development of Bilingual Russian/ English Speaking Children Living in the United States: A Review of the Literature

- The acquisition of syllable structure by Russian-speaking children with SLI

To determine information about the children’s language development and language environment, in both their first and second language, visit the CHESL Centre website for The Alberta Language Development Questionnaire and The Alberta Language Environment Questionnaire

There you have it! FREE bilingual/multicultural SLP resources compiled for you conveniently in one place. And since there are much more FREE GEMS online, I’d love it if you guys contributed to and expanded this modest list by posting links and title descriptions in the comments section below for others to benefit from!

Together we can deliver the most up to date evidence-based assessment and intervention to bilingual and multicultural students that we serve! Click HERE to check out the FREE Resources in the SLPs for Evidence-Based Practice Group

Helpful Bilingual Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

- Checklist for Identification of Speech-Language Disorders in Bilingual and Multicultural Children

- Multicultural Assessment Bundle

- Best Practices in Bilingual Literacy Assessments and Interventions

- Dynamic Assessment of Bilingual and Multicultural Learners in Speech-Language Pathology

- Practical Strategies for Monolingual SLPs Assessing and Treating Bilingual Children

- Language Difference vs. Language Disorder: Assessment & Intervention Strategies for SLPs Working with Bilingual Children

- Impact of Cultural and Linguistic Variables On Speech-Language Services

- Assessment of sound and syllable imitation in Russian-speaking infants and toddlers

- Russian Articulation Screener

- Creating Translanguaging Classrooms and Therapy Rooms

Gauging Moods and Interpreting Abstract Emotional States

Tuesday July 30th is Trivia Night!

This Tuesday is my turn to host SLP Trivia Night. Created by Kristine of Simply Speech (graphic by Carrie of Carrie’s Speech Corner), Trivia Night involves different SLP Bloggers hosting a night of trivia SLP related questions on their respective Facebook pages. Jen of Speech Universe did it on July 16, Jocelyn of Ms. Jocelyn Speech did it on July 23rd and now it’s my turn.

Tomorrow (Tuesday, July 30th) I will be hosting this event on my Facebook Page at 9:00 p.m EST. I am going to have three different rounds at

1. 9:00 pm: First round is on Early Child Development

2. 9:15 pm: Second round is on Internationally Adopted (IA) Children

3. 9:30 pm: Third round is on Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD)

Each round will consist of 5 questions on each of the above topics. Each set of questions will be posted on my blog with a link provided on my Facebook Page.

Contestants will be asked to answer ALL 5 questions under the blog entry for a chance to win.

In each round the first person to get all 5 questions correct will have their choice of products from my online store. I hope to see you all there for SLP Trivia Night!

Spotlight on Syndromes: An SLPs Perspective on Hurler Syndrome

Today’s guest post on genetic syndromes comes from Kelly Hungaski, who is contributing an informative piece on the Hurler Syndrome.

Hurler Syndrome is a rare, inherited metabolic disease in which a person can’t break down lengthy chains of sugar molecules called glycosaminoglycans. Hurler syndrome belongs to a group of diseases called mucopolysaccharidoses, or MPS. Continue reading Spotlight on Syndromes: An SLPs Perspective on Hurler Syndrome

Speech Language Assessment Checklist for Adolescents