Picture books are absolutely wonderful for both assessment and treatment purposes! They are terrific as narrative elicitation aids for children of various ages, ranging from pre-K through fourth grade. They are amazing treatment aids for addressing a variety of speech, language, and literacy goals that extend far beyond narrative production. Continue reading Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Helen Lester’s Picture Books

Picture books are absolutely wonderful for both assessment and treatment purposes! They are terrific as narrative elicitation aids for children of various ages, ranging from pre-K through fourth grade. They are amazing treatment aids for addressing a variety of speech, language, and literacy goals that extend far beyond narrative production. Continue reading Speech, Language, and Literacy Fun with Helen Lester’s Picture Books

Category: Critical Thinking

On the Disadvantages of Parents Ceasing to Speak the Birth Language with Bilingual Language Impaired Children

Despite significant advances in the fields of education and speech pathology, many harmful myths pertaining to multilingualism continue to persist. One particularly infuriating and patently incorrect recommendation to parents is the advice to stop speaking the birth language with their bilingual children with language disorders. Continue reading On the Disadvantages of Parents Ceasing to Speak the Birth Language with Bilingual Language Impaired Children

Despite significant advances in the fields of education and speech pathology, many harmful myths pertaining to multilingualism continue to persist. One particularly infuriating and patently incorrect recommendation to parents is the advice to stop speaking the birth language with their bilingual children with language disorders. Continue reading On the Disadvantages of Parents Ceasing to Speak the Birth Language with Bilingual Language Impaired Children

Analyzing Discourse Abilities of Adolescents via Peer Conflict Resolution (PCR) Tasks

A substantial portion of my caseload is comprised of adolescent learners. Since standardized assessments possess significant limitations for that age group (as well as in general), I am frequently on the lookout for qualitative clinical measures that can accurately capture their abilities in the areas of discourse, critical thinking, and social communication.

A substantial portion of my caseload is comprised of adolescent learners. Since standardized assessments possess significant limitations for that age group (as well as in general), I am frequently on the lookout for qualitative clinical measures that can accurately capture their abilities in the areas of discourse, critical thinking, and social communication.

One type of an assessment that I find particularly valuable for this age group is a set of two Peer Conflict Resolution Tasks. First described in a 2007 article by Dr. Marylin Nippold and her colleagues, they assess expository discourse of adolescent learners. Continue reading Analyzing Discourse Abilities of Adolescents via Peer Conflict Resolution (PCR) Tasks

Do Our Therapy Goals Make Sense or How to Create Functional Language Intervention Targets

In the past several years, I wrote a series of posts on the topic of improving clinical practices in speech-language pathology. Some of these posts were based on my clinical experience as backed by research, while others summarized key point from articles written by prominent colleagues in our field such as Dr. Alan Kamhi, Dr. David DeBonnis, Dr. Andrew Vermiglio, etc.

In the past several years, I wrote a series of posts on the topic of improving clinical practices in speech-language pathology. Some of these posts were based on my clinical experience as backed by research, while others summarized key point from articles written by prominent colleagues in our field such as Dr. Alan Kamhi, Dr. David DeBonnis, Dr. Andrew Vermiglio, etc.

In the past, I have highlighted several articles from the 2014 LSHSS clinical forum entitled: Improving Clinical Practice. Today I would like to explicitly summarize another relevant article written by Dr. Wallach in 2014, entitled “Improving Clinical Practice: A School-Age and School-Based Perspective“, which discusses how to change the “persistence of traditional practices” in order to make our language interventions more functional and meaningful for students with language learning difficulties. Continue reading Do Our Therapy Goals Make Sense or How to Create Functional Language Intervention Targets

Help, My Student has a Huge Score Discrepancy Between Tests and I Don’t Know Why?

Here’s a familiar scenario to many SLPs. You’ve administered several standardized language tests to your student (e.g., CELF-5 & TILLS). You expected to see roughly similar scores across tests. Much to your surprise, you find that while your student attained somewhat average scores on one assessment, s/he had completely bombed the second assessment, and you have no idea why that happened.

Here’s a familiar scenario to many SLPs. You’ve administered several standardized language tests to your student (e.g., CELF-5 & TILLS). You expected to see roughly similar scores across tests. Much to your surprise, you find that while your student attained somewhat average scores on one assessment, s/he had completely bombed the second assessment, and you have no idea why that happened.

So you go on social media and start crowdsourcing for information from a variety of SLPs located in a variety of states and countries in order to figure out what has happened and what you should do about this. Of course, the problem in such situations is that while some responses will be spot on, many will be utterly inappropriate. Luckily, the answer lies much closer than you think, in the actual technical manual of the administered tests.

So what is responsible for such as drastic discrepancy? A few things actually. For starters, unless both tests were co-normed (used the same sample of test takers) be prepared to see disparate scores due to the ability levels of children in the normative groups of each test. Another important factor involved in the score discrepancy is how accurately does the test differentiate disordered children from typical functioning ones.

Let’s compare two actual language tests to learn more. For the purpose of this exercise let us select The Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-5 (CELF-5) and the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy (TILLS). The former is a very familiar entity to numerous SLPs, while the latter is just coming into its own, having been released in the market only several years ago.

Both tests share a number of similarities. Both were created to assess the language abilities of children and adolescents with suspected language disorders. Both assess aspects of language and literacy (albeit not to the same degree nor with the same level of thoroughness). Both can be used for language disorder classification purposes, or can they?

Actually, my last statement is rather debatable. A careful perusal of the CELF – 5 reveals that its normative sample of 3000 children included a whopping 23% of children with language-related disabilities. In fact, the folks from the Leaders Project did such an excellent and thorough job reviewing its psychometric properties rather than repeating that information, the readers can simply click here to review the limitations of the CELF – 5 straight on the Leaders Project website. Furthermore, even the CELF – 5 developers themselves have stated that: “Based on CELF-5 sensitivity and specificity values, the optimal cut score to achieve the best balance is -1.33 (standard score of 80). Using a standard score of 80 as a cut score yields sensitivity and specificity values of .97. “

Actually, my last statement is rather debatable. A careful perusal of the CELF – 5 reveals that its normative sample of 3000 children included a whopping 23% of children with language-related disabilities. In fact, the folks from the Leaders Project did such an excellent and thorough job reviewing its psychometric properties rather than repeating that information, the readers can simply click here to review the limitations of the CELF – 5 straight on the Leaders Project website. Furthermore, even the CELF – 5 developers themselves have stated that: “Based on CELF-5 sensitivity and specificity values, the optimal cut score to achieve the best balance is -1.33 (standard score of 80). Using a standard score of 80 as a cut score yields sensitivity and specificity values of .97. “

In other words, obtaining a standard score of 80 on the CELF – 5 indicates that a child presents with a language disorder. Of course, as many SLPs already know, the eligibility criteria in the schools requires language scores far below that in order for the student to qualify to receive language therapy services.

In fact, the test’s authors are fully aware of that and acknowledge that in the same document. “Keep in mind that students who have language deficits may not obtain scores that qualify him or her for placement based on the program’s criteria for eligibility. You’ll need to plan how to address the student’s needs within the framework established by your program.”

But here is another issue – the CELF-5 sensitivity group included only a very small number of: “67 children ranging from 5;0 to 15;11”, whose only requirement was to score 1.5SDs < mean “on any standardized language test”. As the Leaders Project reviewers point out: “This means that the 67 children in the sensitivity group could all have had severe disabilities. They might have multiple disabilities in addition to severe language disorders including severe intellectual disabilities or Autism Spectrum Disorder making it easy for a language disorder test to identify this group as having language disorders with extremely high accuracy. ” (pgs. 7-8)

But here is another issue – the CELF-5 sensitivity group included only a very small number of: “67 children ranging from 5;0 to 15;11”, whose only requirement was to score 1.5SDs < mean “on any standardized language test”. As the Leaders Project reviewers point out: “This means that the 67 children in the sensitivity group could all have had severe disabilities. They might have multiple disabilities in addition to severe language disorders including severe intellectual disabilities or Autism Spectrum Disorder making it easy for a language disorder test to identify this group as having language disorders with extremely high accuracy. ” (pgs. 7-8)

Of course, this begs the question, why would anyone continue to administer any test to students, if its administration A. Does not guarantee disorder identification B. Will not make the student eligible for language therapy despite demonstrated need?

The problem is that even though SLPs are mandated to use a variety of quantitative clinical observations and procedures in order to reliably qualify students for services, standardized tests still carry more value then they should. Consequently, it is important for SLPs to select the right test to make their job easier.

The TILLS is a far less known assessment than the CELF-5 yet in the few years it has been out on the market it really made its presence felt by being a solid assessment tool due to its valid and reliable psychometric properties. Again, the venerable Dr. Carol Westby had already done such an excellent job reviewing its psychometric properties that I will refer the readers to her review here, rather than repeating this information as it will not add anything new on this topic. The upshot of her review as follows: “The TILLS does not include children and adolescents with language/literacy impairments (LLIs) in the norming sample. Since the 1990s, nearly all language assessments have included children with LLIs in the norming sample. Doing so lowers overall scores, making it more difficult to use the assessment to identify students with LLIs. (pg. 11)”

The TILLS is a far less known assessment than the CELF-5 yet in the few years it has been out on the market it really made its presence felt by being a solid assessment tool due to its valid and reliable psychometric properties. Again, the venerable Dr. Carol Westby had already done such an excellent job reviewing its psychometric properties that I will refer the readers to her review here, rather than repeating this information as it will not add anything new on this topic. The upshot of her review as follows: “The TILLS does not include children and adolescents with language/literacy impairments (LLIs) in the norming sample. Since the 1990s, nearly all language assessments have included children with LLIs in the norming sample. Doing so lowers overall scores, making it more difficult to use the assessment to identify students with LLIs. (pg. 11)”

Now, here many proponents of inclusion of children with language disorders in the normative sample will make a variation of the following claim: “You CANNOT diagnose a language impairment if children with language impairment were not included in the normative sample of that assessment!” Here’s a major problem with such assertion. When a child is referred for a language assessment, we really have no way of knowing if this child has a language impairment until we actually finish testing them. We are in fact attempting to confirm or refute this fact, hopefully via the use of reliable and valid testing. However, if the normative sample includes many children with language and learning difficulties, this significantly affects the accuracy of our identification, since we are interested in comparing this child’s results to typically developing children and not the disordered ones, in order to learn if the child has a disorder in the first place. As per Peña, Spaulding and Plante (2006), “the inclusion of children with disabilities may be at odds with the goal of classification, typically the primary function of the speech pathologist’s assessment. In fact, by including such children in the normative sample, we may be “shooting ourselves in the foot” in terms of testing for the purpose of identifying disorders.”(p. 248)

Then there’s a variation of this assertion, which I have seen in several Facebook groups: “Children with language disorders score at the low end of normal distribution“. Once again such assertion is incorrect since Spaulding, Plante & Farinella (2006) have actually shown that on average, these kids will score at least 1.28 SDs below the mean, which is not the low average range of normal distribution by any means. As per authors: “Specific data supporting the application of “low score” criteria for the identification of language impairment is not supported by the majority of current commercially available tests. However, alternate sources of data (sensitivity and specificity rates) that support accurate identification are available for a subset of the available tests.” (p. 61)

Then there’s a variation of this assertion, which I have seen in several Facebook groups: “Children with language disorders score at the low end of normal distribution“. Once again such assertion is incorrect since Spaulding, Plante & Farinella (2006) have actually shown that on average, these kids will score at least 1.28 SDs below the mean, which is not the low average range of normal distribution by any means. As per authors: “Specific data supporting the application of “low score” criteria for the identification of language impairment is not supported by the majority of current commercially available tests. However, alternate sources of data (sensitivity and specificity rates) that support accurate identification are available for a subset of the available tests.” (p. 61)

Now, let us get back to your child in question, who performed so differently on both of the administered tests. Given his clinically observed difficulties, you fully expected your testing to confirm it. But you are now more confused than before. Don’t be! Search the technical manual for information on the particular test’s sensitivity and specificity to look up the numbers. Vance and Plante (1994) put forth the following criteria for accurate identification of a disorder (discriminant accuracy): “90% should be considered good discriminant accuracy; 80% to 89% should be considered fair. Below 80%, misidentifications occur at unacceptably high rates” and leading to “serious social consequences” of misidentified children. (p. 21)

Review the sensitivity and specificity of your test/s, take a look at the normative samples, see if anything unusual jumps out at you, which leads you to believe that the administered test may have some issues with assessing what it purports to assess. Then, after supplementing your standardized testing results with good quality clinical data (e.g., narrative samples, dynamic assessment tasks, etc.), consider creating a solidly referenced purchasing pitch to your administration to invest in more valid and reliable standardized tests.

Hope you find this information helpful in your quest to better serve the clients on your caseload. If you are interested in learning more regarding evidence-based assessment practices as well as psychometric properties of various standardized speech-language tests visit the SLPs for Evidence-Based Practice group on Facebook learn more.

References:

- Peña ED, Spaulding TJ, and Plante E. ( 2006) The composition of normative groups and diagnostic decision-making: Shooting ourselves in the foot. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 15: 247–54.

- Spaulding, T. J., Plante, E., & Farinella, K. A. (2006). Eligibility criteria for language impairment: Is the low end of normal always appropriate? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37, 61-72.

- Vance, R., & Plante, E. (1994). Selection of preschool language tests: A data-based approach. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 25, 15-24.

It’s All Due to …Language: How Subtle Symptoms Can Cause Serious Academic Deficits

Scenario: Len is a 7-2-year-old, 2nd-grade student who struggles with reading and writing in the classroom. He is very bright and has a high average IQ, yet when he is speaking he frequently can’t get his point across to others due to excessive linguistic reformulations and word-finding difficulties. The problem is that Len passed all the typical educational and language testing with flying colors, receiving average scores across the board on various tests including the Woodcock-Johnson Fourth Edition (WJ-IV) and the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-5 (CELF-5). Stranger still is the fact that he aced Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing, Second Edition (CTOPP-2), with flying colors, so he is not even eligible for a “dyslexia” diagnosis. Len is clearly struggling in the classroom with coherently expressing self, telling stories, understanding what he is reading, as well as putting his thoughts on paper. His parents have compiled impressively huge folders containing examples of his struggles. Yet because of his performance on the basic standardized assessment batteries, Len does not qualify for any functional assistance in the school setting, despite being virtually functionally illiterate in second grade.

Scenario: Len is a 7-2-year-old, 2nd-grade student who struggles with reading and writing in the classroom. He is very bright and has a high average IQ, yet when he is speaking he frequently can’t get his point across to others due to excessive linguistic reformulations and word-finding difficulties. The problem is that Len passed all the typical educational and language testing with flying colors, receiving average scores across the board on various tests including the Woodcock-Johnson Fourth Edition (WJ-IV) and the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-5 (CELF-5). Stranger still is the fact that he aced Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing, Second Edition (CTOPP-2), with flying colors, so he is not even eligible for a “dyslexia” diagnosis. Len is clearly struggling in the classroom with coherently expressing self, telling stories, understanding what he is reading, as well as putting his thoughts on paper. His parents have compiled impressively huge folders containing examples of his struggles. Yet because of his performance on the basic standardized assessment batteries, Len does not qualify for any functional assistance in the school setting, despite being virtually functionally illiterate in second grade.

The truth is that Len is quite a familiar figure to many SLPs, who at one time or another have encountered such a student and asked for guidance regarding the appropriate accommodations and services for him on various SLP-geared social media forums. But what makes Len such an enigma, one may inquire? Surely if the child had tangible deficits, wouldn’t standardized testing at least partially reveal them?

Well, it all depends really, on what type of testing was administered to Len in the first place. A few years ago I wrote a post entitled: “What Research Shows About the Functional Relevance of Standardized Language Tests“. What researchers found is that there is a “lack of a correlation between frequency of test use and test accuracy, measured both in terms of sensitivity/specificity and mean difference scores” (Betz et al, 2012, 141). Furthermore, they also found that the most frequently used tests were the comprehensive assessments including the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals and the Preschool Language Scale as well as one-word vocabulary tests such as the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test”. Most damaging finding was the fact that: “frequently SLPs did not follow up the comprehensive standardized testing with domain-specific assessments (critical thinking, social communication, etc.) but instead used the vocabulary testing as a second measure”.(Betz et al, 2012, 140)

In other words, many SLPs only use the tests at hand rather than the RIGHT tests aimed at identifying the student’s specific deficits. But the problem doesn’t actually stop there. Due to the variation in psychometric properties of various tests, many children with language impairment are overlooked by standardized tests by receiving scores within the average range or not receiving low enough scores to qualify for services.

Thus, “the clinical consequence is that a child who truly has a language impairment has a roughly equal chance of being correctly or incorrectly identified, depending on the test that he or she is given.” Furthermore, “even if a child is diagnosed accurately as language impaired at one point in time, future diagnoses may lead to the false perception that the child has recovered, depending on the test(s) that he or she has been given (Spaulding, Plante & Farinella, 2006, 69).”

There’s of course yet another factor affecting our hypothetical client and that is his relatively young age. This is especially evident with many educational and language testing for children in the 5-7 age group. Because the bar is set so low, concept-wise for these age-groups, many children with moderate language and literacy deficits can pass these tests with flying colors, only to be flagged by them literally two years later and be identified with deficits, far too late in the game. Coupled with the fact that many SLPs do not utilize non-standardized measures to supplement their assessments, Len is in a pretty serious predicament.

But what if there was a do-over? What could we do differently for Len to rectify this situation? For starters, we need to pay careful attention to his deficits profile in order to choose appropriate tests to evaluate his areas of needs. The above can be accomplished via a number of ways. The SLP can interview Len’s teacher and his caregiver/s in order to obtain a summary of his pressing deficits. Depending on the extent of the reported deficits the SLP can also provide them with a referral checklist to mark off the most significant areas of need.

In Len’s case, we already have a pretty good idea regarding what’s going on. We know that he passed basic language and educational testing, so in the words of Dr. Geraldine Wallach, we need to keep “peeling the onion” via the administration of more sensitive tests to tap into Len’s reported areas of deficits which include: word-retrieval, narrative production, as well as reading and writing.

For that purpose, Len is a good candidate for the administration of the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy (TILLS), which was developed to identify language and literacy disorders, has good psychometric properties, and contains subtests for assessment of relevant skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, phonological awareness, spelling, as well as writing in school-age children.

For that purpose, Len is a good candidate for the administration of the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy (TILLS), which was developed to identify language and literacy disorders, has good psychometric properties, and contains subtests for assessment of relevant skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, phonological awareness, spelling, as well as writing in school-age children.

Given Len’s reported history of narrative production deficits, Len is also a good candidate for the administration of the Social Language Development Test Elementary (SLDTE). Here’s why. Research indicates that narrative weaknesses significantly correlate with social communication deficits (Norbury, Gemmell & Paul, 2014). As such, it’s not just children with Autism Spectrum Disorders who present with impaired narrative abilities. Many children with developmental language impairment (DLD) (#devlangdis) can present with significant narrative deficits affecting their social and academic functioning, which means that their social communication abilities need to be tested to confirm/rule out presence of these difficulties.

Given Len’s reported history of narrative production deficits, Len is also a good candidate for the administration of the Social Language Development Test Elementary (SLDTE). Here’s why. Research indicates that narrative weaknesses significantly correlate with social communication deficits (Norbury, Gemmell & Paul, 2014). As such, it’s not just children with Autism Spectrum Disorders who present with impaired narrative abilities. Many children with developmental language impairment (DLD) (#devlangdis) can present with significant narrative deficits affecting their social and academic functioning, which means that their social communication abilities need to be tested to confirm/rule out presence of these difficulties.

However, standardized tests are not enough, since even the best-standardized tests have significant limitations. As such, several non-standardized assessments in the areas of narrative production, reading, and writing, may be recommended for Len to meaningfully supplement his testing.

Let’s begin with an informal narrative assessment which provides detailed information regarding microstructural and macrostructural aspects of storytelling as well as child’s thought processes and socio-emotional functioning. My nonstandardized narrative assessments are based on the book elicitation recommendations from the SALT website. For 2nd graders, I use the book by Helen Lester entitled Pookins Gets Her Way. I first read the story to the child, then cover up the words and ask the child to retell the story based on pictures. I read the story first because: “the model narrative presents the events, plot structure, and words that the narrator is to retell, which allows more reliable scoring than a generated story that can go in many directions” (Allen et al, 2012, p. 207).

As the child is retelling his story I digitally record him using the Voice Memos application on my iPhone, for a later transcription and thorough analysis. During storytelling, I only use the prompts: ‘What else can you tell me?’ and ‘Can you tell me more?’ to elicit additional information. I try not to prompt the child excessively since I am interested in cataloging all of his narrative-based deficits. After I transcribe the sample, I analyze it and make sure that I include the transcription and a detailed write-up in the body of my report, so parents and professionals can see and understand the nature of the child’s errors/weaknesses.

Now we are ready to move on to a brief nonstandardized reading assessment. For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Reading for Comprehension, which contains books for grades 1-8. After I confirm with either the parent or the child’s teacher that the selected passage is reflective of the complexity of work presented in the classroom for his grade level, I ask the child to read the text. As the child is reading, I calculate the correct number of words he reads per minute as well as what type of errors the child is exhibiting during reading. Then I ask the child to state the main idea of the text, summarize its key points as well as define select text embedded vocabulary words and answer a few, verbally presented reading comprehension questions. After that, I provide the child with accompanying 5 multiple choice question worksheet and ask the child to complete it. I analyze my results in order to determine whether I have accurately captured the child’s reading profile.

Now we are ready to move on to a brief nonstandardized reading assessment. For this purpose, I often use the books from the Continental Press series entitled: Reading for Comprehension, which contains books for grades 1-8. After I confirm with either the parent or the child’s teacher that the selected passage is reflective of the complexity of work presented in the classroom for his grade level, I ask the child to read the text. As the child is reading, I calculate the correct number of words he reads per minute as well as what type of errors the child is exhibiting during reading. Then I ask the child to state the main idea of the text, summarize its key points as well as define select text embedded vocabulary words and answer a few, verbally presented reading comprehension questions. After that, I provide the child with accompanying 5 multiple choice question worksheet and ask the child to complete it. I analyze my results in order to determine whether I have accurately captured the child’s reading profile.

Finally, if any additional information is needed, I administer a nonstandardized writing assessment, which I base on the Common Core State Standards for 2nd grade. For this task, I provide a student with a writing prompt common for second grade and give him a period of 15-20 minutes to generate a writing sample. I then analyze the writing sample with respect to contextual conventions (punctuation, capitalization, grammar, and syntax) as well as story composition (overall coherence and cohesion of the written sample).

The above relatively short assessment battery (2 standardized tests and 3 informal assessment tasks) which takes approximately 2-2.5 hours to administer, allows me to create a comprehensive profile of the child’s language and literacy strengths and needs. It also allows me to generate targeted goals in order to begin effective and meaningful remediation of the child’s deficits.

Children like Len will, unfortunately, remain unidentified unless they are administered more sensitive tasks to better understand their subtle pattern of deficits. Consequently, to ensure that they do not fall through the cracks of our educational system due to misguided overreliance on a limited number of standardized assessments, it is very important that professionals select the right assessments, rather than the assessments at hand, in order to accurately determine the child’s areas of needs.

References:

- Allen, M, Ukrainetz, T & Carswell, A (2012) The narrative language performance of three types of at-risk first-grade readers. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 43(2), 205-221.

- Betz et al. (2013) Factors Influencing the Selection of Standardized Tests for the Diagnosis of Specific Language Impairment. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 44, 133-146.

- Hasbrouck, J. & Tindal, G. A. (2006). Oral reading fluency norms: A valuable assessment tool for reading teachers. The Reading Teacher. 59(7), 636-644.).

- Norbury, C. F., Gemmell, T., & Paul, R. (2014). Pragmatics abilities in narrative production: a cross-disorder comparison. Journal of child language, 41(03), 485-510.

- Peña, E.D., Spaulding, T.J., & Plante, E. (2006). The Composition of Normative Groups and Diagnostic Decision Making: Shooting Ourselves in the Foot. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15, 247-254.

- Spaulding, Plante & Farinella (2006) Eligibility Criteria for Language Impairment: Is the Low End of Normal Always Appropriate? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 37, 61-72.

- Spaulding, Szulga, & Figueria (2012) Using Norm-Referenced Tests to Determine Severity of Language Impairment in Children: Disconnect Between U.S. Policy Makers and Test Developers. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 43, 176-190.

Improving Executive Function Skills of Language Impaired Students with Hedbanz

Those of you who have previously read my blog know that I rarely use children’s games to address language goals. However, over the summer I have been working on improving executive function abilities (EFs) of some of the language impaired students on my caseload. As such, I found select children’s games to be highly beneficial for improving language-based executive function abilities.

Those of you who have previously read my blog know that I rarely use children’s games to address language goals. However, over the summer I have been working on improving executive function abilities (EFs) of some of the language impaired students on my caseload. As such, I found select children’s games to be highly beneficial for improving language-based executive function abilities.

For those of you who are only vaguely familiar with this concept, executive functions are higher level cognitive processes involved in the inhibition of thought, action, and emotion, which located in the prefrontal cortex of the frontal lobe of the brain. The development of executive functions begins in early infancy; but it can be easily disrupted by a number of adverse environmental and organic experiences (e.g., psychosocial deprivation, trauma). Furthermore, research in this area indicates that the children with language impairments present with executive function weaknesses which require remediation.

EF components include working memory, inhibitory control, planning, and set-shifting.

- Working memory

- Ability to store and manipulate information in mind over brief periods of time

- Inhibitory control

- Suppressing responses that are not relevant to the task

- Set-shifting

- Ability to shift behavior in response to changes in tasks or environment

Simply put, EFs contribute to the child’s ability to sustain attention, ignore distractions, and succeed in academic settings. By now some of you must be wondering: “So what does Hedbanz have to do with any of it?”

Well, Hedbanz is a quick-paced multiplayer (2-6 people) game of “What Am I?” for children ages 7 and up. Players get 3 chips and wear a “picture card” in their headband. They need to ask questions in rapid succession to figure out what they are. “Am I fruit?” “Am I a dessert?” “Am I sports equipment?” When they figure it out, they get rid of a chip. The first player to get rid of all three chips wins.

The game sounds deceptively simple. Yet if any SLPs or parents have ever played that game with their language impaired students/children as they would be quick to note how extraordinarily difficult it is for the children to figure out what their card is. Interestingly, in my clinical experience, I’ve noticed that it’s not just moderately language impaired children who present with difficulty playing this game. Even my bright, average intelligence teens, who have passed vocabulary and semantic flexibility testing (such as the WORD Test 2-Adolescent or the Vocabulary Awareness subtest of the Test of Integrated Language and Literacy ) significantly struggle with their language organization when playing this game.

So what makes Hedbanz so challenging for language impaired students? Primarily, it’s the involvement and coordination of the multiple executive functions during the game. In order to play Hedbanz effectively and effortlessly, the following EF involvement is needed:

- Task Initiation

- Students with executive function impairments will often “freeze up” and as a result may have difficulty initiating the asking of questions in the game because many will not know what kind of questions to ask, even after extensive explanations and elaborations by the therapist.

- Organization

- Students with executive function impairments will present with difficulty organizing their questions by meaningful categories and as a result will frequently lose their track of thought in the game.

- Working Memory

- This executive function requires the student to keep key information in mind as well as keep track of whatever questions they have already asked.

- Flexible Thinking

- This executive function requires the student to consider a situation from multiple angles in order to figure out the quickest and most effective way of arriving at a solution. During the game, students may present with difficulty flexibly generating enough organizational categories in order to be effective participants.

- Impulse Control

- Many students with difficulties in this area may blurt out an inappropriate category or in an appropriate question without thinking it through first.

- They may also present with difficulty set-shifting. To illustrate, one of my 13-year-old students with ASD, kept repeating the same question when it was his turn, despite the fact that he was informed by myself as well as other players of the answer previously.

- Many students with difficulties in this area may blurt out an inappropriate category or in an appropriate question without thinking it through first.

- Emotional Control

- This executive function will help students with keeping their emotions in check when the game becomes too frustrating. Many students of difficulties in this area will begin reacting behaviorally when things don’t go their way and they are unable to figure out what their card is quickly enough. As a result, they may have difficulty mentally regrouping and reorganizing their questions when something goes wrong in the game.

- Self-Monitoring

- This executive function allows the students to figure out how well or how poorly they are doing in the game. Students with poor insight into own abilities may present with difficulty understanding that they are doing poorly and may require explicit instruction in order to change their question types.

- Planning and Prioritizing

- Students with poor abilities in this area will present with difficulty prioritizing their questions during the game.

Consequently, all of the above executive functions can be addressed via language-based goals. However, before I cover that, I’d like to review some of my session procedures first.

Typically, long before game initiation, I use the cards from the game to prep the students by teaching them how to categorize and classify presented information so they effectively and efficiently play the game.

Rather than using the “tip cards”, I explain to the students how to categorize information effectively.

Rather than using the “tip cards”, I explain to the students how to categorize information effectively.

This, in turn, becomes a great opportunity for teaching students relevant vocabulary words, which can be extended far beyond playing the game.

I begin the session by explaining to the students that pretty much everything can be roughly divided into two categories animate (living) or inanimate (nonliving) things. I explain that humans, animals, as well as plants belong to the category of living things, while everything else belongs to the category of inanimate objects. I further divide the category of inanimate things into naturally existing and man-made items. I explain to the students that the naturally existing category includes bodies of water, landmarks, as well as things in space (moon, stars, sky, sun, etc.). In contrast, things constructed in factories or made by people would be example of man-made objects (e.g., building, aircraft, etc.)

When I’m confident that the students understand my general explanations, we move on to discuss further refinement of these broad categories. If a student determines that their card belongs to the category of living things, we discuss how from there the student can further determine whether they are an animal, a plant, or a human. If a student determined that their card belongs to the animal category, we discuss how we can narrow down the options of figuring out what animal is depicted on their card by asking questions regarding their habitat (“Am I a jungle animal?”), and classification (“Am I a reptile?”). From there, discussion of attributes prominently comes into play. We discuss shapes, sizes, colors, accessories, etc., until the student is able to confidently figure out which animal is depicted on their card.

In contrast, if the student’s card belongs to the inanimate category of man-made objects, we further subcategorize the information by the object’s location (“Am I found outside or inside?”; “Am I found in ___ room of the house?”, etc.), utility (“Can I be used for ___?”), as well as attributes (e.g., size, shape, color, etc.)

Thus, in addition to improving the students’ semantic flexibility skills (production of definitions, synonyms, attributes, etc.) the game teaches the students to organize and compartmentalize information in order to effectively and efficiently arrive at a conclusion in the most time expedient fashion.

Now, we are ready to discuss what type of EF language-based goals, SLPs can target by simply playing this game.

1. Initiation: Student will initiate questioning during an activity in __ number of instances per 30-minute session given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

2. Planning: Given a specific routine, student will verbally state the order of steps needed to complete it with __% accuracy given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

3. Working Memory: Student will repeat clinician provided verbal instructions pertaining to the presented activity, prior to its initiation, with 80% accuracy given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

4. Flexible Thinking: Following a training by the clinician, student will generate at least __ questions needed for task completion (e.g., winning the game) with __% accuracy given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

5. Organization: Student will use predetermined written/visual cues during an activity to assist self with organization of information (e.g., questions to ask) with __% accuracy given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

6. Impulse Control: During the presented activity the student will curb blurting out inappropriate responses (by silently counting to 3 prior to providing his response) in __ number of instances per 30 minute session given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

7. Emotional Control: When upset, student will verbalize his/her frustration (vs. behavioral activing out) in __ number of instances per 30 minute session given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

8. Self-Monitoring: Following the completion of an activity (e.g., game) student will provide insight into own strengths and weaknesses during the activity (recap) by verbally naming the instances in which s/he did well, and instances in which s/he struggled with __% accuracy given (maximal, moderate, minimal) type of ___ (phonemic, semantic, etc.) prompts and __ (visual, gestural, tactile, etc.) cues by the clinician.

There you have it. This one simple game doesn’t just target a plethora of typical expressive language goals. It can effectively target and improve language-based executive function goals as well. Considering the fact that it sells for approximately $12 on Amazon.com, that’s a pretty useful therapy material to have in one’s clinical tool repertoire. For fancier versions, clinicians can use “Jeepers Peepers” photo card sets sold by Super Duper Inc. Strapped for cash, due to highly limited budget? You can find plenty of free materials online if you simply input “Hedbanz cards” in your search query on Google. So have a little fun in therapy, while your students learn something valuable in the process and play Hedbanz today!

Related Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

The End of See it, Zap it! Ankyloglossia (Tongue-Tie) Controversies in Research and Clinical Practice

Today it is my pleasure and privilege to interview 3 Australian lactation consultations: Lois Wattis, Renee Kam, and Pamela Douglas, the authors of a March 2017 article in the Breastfeeding Review: “Three experienced lactation consultants reflect upon the oral tie phenomenon” (which can be found HERE).

Today it is my pleasure and privilege to interview 3 Australian lactation consultations: Lois Wattis, Renee Kam, and Pamela Douglas, the authors of a March 2017 article in the Breastfeeding Review: “Three experienced lactation consultants reflect upon the oral tie phenomenon” (which can be found HERE).

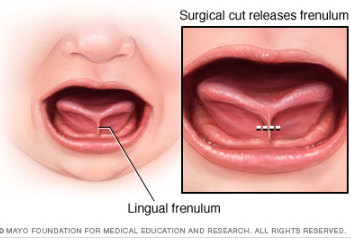

Tatyana Elleseff: Colleagues, as you very well know, the subject of ankyloglossia or tongue tie affecting breastfeeding and speech production has risen into significant prominence in the past several years. Numerous journal articles, blog posts, as well as social media forums have been discussing this phenomenon with rather conflicting recommendations. Many health professionals and parents are convinced that “releasing the tie” or performing either a frenotomy or frenectomy will lead to significant improvements in speech and feeding.

Presently, systematic reviews1-3 demonstrate there is insufficient evidence for the above. However, when many professionals including myself, cite reputable research explaining the lack of support of surgical intervention for tongue tie, there has been a pushback on the part of a number of other health professionals including lactation consultants, nurses, dentists, as well as speech-language pathologists stating that in their clinical experience surgical intervention does resolve issues with tongue tie as related to speech and feeding.

Presently, systematic reviews1-3 demonstrate there is insufficient evidence for the above. However, when many professionals including myself, cite reputable research explaining the lack of support of surgical intervention for tongue tie, there has been a pushback on the part of a number of other health professionals including lactation consultants, nurses, dentists, as well as speech-language pathologists stating that in their clinical experience surgical intervention does resolve issues with tongue tie as related to speech and feeding.

So today, given your 33 combined years of practice as lactation consultants I would love to ask your some questions regarding the tongue tie phenomena.

I would like to begin our discussion with a description of normal breastfeeding and what can interfere with it from an anatomical and physiological standpoint for mothers and babies.

Now, many of this blog’s readers already know that a tongue tie occurs when the connective tissue under the tongue known as a lingual frenulum restricts tongue movement to some degree and adversely affects its function. But many may not realize that children can present with a normal anatomical variant of “ties” which can be completely asymptomatic. Can you please address that?

Now, many of this blog’s readers already know that a tongue tie occurs when the connective tissue under the tongue known as a lingual frenulum restricts tongue movement to some degree and adversely affects its function. But many may not realize that children can present with a normal anatomical variant of “ties” which can be completely asymptomatic. Can you please address that?

Lois Wattis: “Normal” breastfeeding takes time and skill to achieve. The breastfeeding dyad is multifactorial, influenced by maternal breast and nipple anatomy combined with the infant’s facial and oral structures, all of which are highly variable. Mothers who have successfully breastfed the first baby may encounter problems with subsequent babies due to size (e.g., smaller, larger, etc.), be compromised by birth interventions or drugs during labor, or incur birth injuries – all of which can affect the initiation of breastfeeding and progression to a happy and comfortable feeding relationship. Unfortunately, the overview of each dyad’s story can be lost when tunnel vision of either health provider or parents regarding the baby’s oral anatomy is believed to be the chief influencer of breastfeeding success or failure.

Tatyana Elleseff: Colleagues, what do we know regarding the true prevalence of various ‘tongue ties’? Are there any studies of good quality?

Pamela Douglas: In a literature review in 2005, Hall and Renfrew acknowledged that the true prevalence of ankyloglossia remained unknown, though they estimated 3-4% of newborns.4

Pamela Douglas: In a literature review in 2005, Hall and Renfrew acknowledged that the true prevalence of ankyloglossia remained unknown, though they estimated 3-4% of newborns.4

After 2005, once the diagnosis of posterior tongue-tie (PTT) had been introduced,5, 6 attempts to quantify incidence of tongue-tie have remained of very poor quality, but estimates currently rest at between 4-10%.7

The problem is that there is a lack of definitional clarity concerning the diagnosis of PTT. Consequently, anterior or classic tongue tie CTT is now often conflated with PTT simply as ‘tongue-tie’ (TT).

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you for clarifying it. In addition to the anterior and posterior tongue tie labels, many parents and professionals also frequently hear the terms lip tie and buccal ties. Is there’s reputable research behind these terms indicating that these ties can truly impact speech and feeding?

Pamela Douglas: Current definitions of ankyloglossia tend to confuse oral and tongue function (which is affected by multiple variables, and in particular by a fit and hold in breastfeeding) with structure (which is highly anatomically variable for both the tongue length and appearance and lingual and maxillary frenula).

For my own purposes, I define CTT as Type 1 and 2 on the Coryllos-Genna-Watson scale.8 In clinical practice, I also find it useful to rate the anterior membrane by the percentage of the undersurface of the tongue into which the membrane connects, applying the first two categories of the Griffiths Classification System.9

There is a wide spectrum of lingual frenula morphologies and elasticities, and deciding where to draw a line between a normal variant and CTT will depend on the clinical judgment concerning the infant’s capacity for pain-free efficient milk transfer. However, that means we need to have an approach to fit and hold that we are confident does optimize pain-free efficient milk transfer and at the moment, research shows that not only do the old ‘hands on’ approach to fit and hold not work, but that baby-led attachment is also not enough for many women. This is why at the Possums Clinic we’ve been working on developing an approach to fit and hold (gestalt breastfeeding) that builds on baby-led attachment but also integrates the findings of the latest ultrasound studies.

I personally don’t find the diagnoses of posterior tongue tie PTT and upper lip tie ULT helpful, and don’t use them. Lois, Renee and myself find that a wide spectrum of normal anatomic lingual and maxillary frenula variants are currently being misdiagnosed as a PTT and ULT, which has worried us and led Lois to initiate the article with Renee.

Tatyana Elleseff: Segueing from the above question: is there an established criterion based upon which a decision is made by relevant professionals to “release” the tie and if so can you explain how it’s determined?

Lois Wattis: When an anterior frenulum is attached at the tongue tip or nearby and is short enough to cause restriction of lift towards the palate, usually associated with extreme discomfort for the breastfeeding mother, I have no reservations about snipping it to release the tongue to enable optimal function for breastfeeding. If a simple frenotomy is going to assist the baby to breastfeed well it is worth doing, and as soon as possible. What I do encounter in my clinical practice are distressed and disempowered mothers whose baby has been labeled as having a posterior tongue tie and/or upper lip tie which is the cause of current and even future problems. Upon examination, the baby has completely normal oral anatomy and breastfeeding upskilling and confidence building of both mother and baby enables the dyad to go forward with strategies which address all elements of their unique story.

Lois Wattis: When an anterior frenulum is attached at the tongue tip or nearby and is short enough to cause restriction of lift towards the palate, usually associated with extreme discomfort for the breastfeeding mother, I have no reservations about snipping it to release the tongue to enable optimal function for breastfeeding. If a simple frenotomy is going to assist the baby to breastfeed well it is worth doing, and as soon as possible. What I do encounter in my clinical practice are distressed and disempowered mothers whose baby has been labeled as having a posterior tongue tie and/or upper lip tie which is the cause of current and even future problems. Upon examination, the baby has completely normal oral anatomy and breastfeeding upskilling and confidence building of both mother and baby enables the dyad to go forward with strategies which address all elements of their unique story.

Although the Hazelbaker Assessment Tool for Lingual Frenulum Function (ATLFF) is a pioneering contribution, bringing us our first systematized approach to examination of the infant’s tongue and oral connective tissues, it is unreliable as a tool for decision-making concerning frenotomy.10-12 In practice many of the item criteria are highly subjective. Although one study found moderate inter-rater reliability on the ATLFF’s structural items, the authors did not find inter-rater reliability on most of the functional items.13 In my clinical experience, there is no reliable correlation between what the tongue is observed to do during oral examinations and what occurs during breastfeeding, other than in the case of classic tongue-tie (excluding congenital craniofacial abnormalities from this discussion.

In my practice as a Lactation Consultant in an acute hospital setting I use a combination of the available assessment tools mainly for documentation purposes, however, the most important tools I use are my eyes and my ears. Observing the mother and baby physical combination and interactions, and suggesting adjustments where indicated to the positioning and attachment technique used (which Pam calls fit and hold) can very often resolve difficulties immediately – even if the baby also has an obvious frenulum under his/her tongue. Listening to the mother’s feedback, and observing the baby’s responses are primary indicators of whether further intervention is needed, or not. Watching how the baby achieves and retains the latch is key, then the examination of baby’s mouth to assess tongue mobility and appearance provide final information about whether baby’s ability to breastfeed comfortably is or is not being hindered by a restrictive lingual frenulum.

Tatyana Elleseff: So frenotomy is an incision (cut) of lingual frenum while frenectomy (complete removal) is an excision of lingual frenum. Both can be performed via various methods of “release”. What effects on breastfeeding have you seen with respect to healing?

Lois Wattis: The significant difference between both procedures involves the degree of invasiveness and level of pain experienced during and after the procedures, and the differing time it takes for the resumption and/or improvement in breastfeeding comfort and efficacy.

It is commonplace for a baby who has had a simple incision to breastfeed immediately after the procedure and exhibit no further signs of discomfort or oral aversion. Conversely, the baby who has had laser division(s) may breastfeed soon after the procedure while topical anesthetics are still working. However, many infants demonstrate discomfort, extreme pain responses and reluctance to feed for days or weeks following a laser treatment. Parents are warned to expect delays resuming feeding and the baby is usually also subjected to wound “stretches” for weeks following the laser treatments. Unfortunately, in my clinical practice I see many parents and babies who are very traumatized by this whole process, and in many cases, breastfeeding can be derailed either temporarily or permanently.

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you! This is highly relevant information for both health professionals and parents alike. I truly appreciate your clinical expertise on this topic. While we are on the topic of restrictive lingual frenulums can we discuss several recent articles published on surgical interventions for the above? For example (Ghaheri, Cole, Fausel, Chuop & Mace, 2016), recently published the result of their study which concluded that: “Surgical release of tongue-tie/lip-tie results in significant improvement in breastfeeding outcomes”. Can you elucidate upon the study design and its findings?

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you! This is highly relevant information for both health professionals and parents alike. I truly appreciate your clinical expertise on this topic. While we are on the topic of restrictive lingual frenulums can we discuss several recent articles published on surgical interventions for the above? For example (Ghaheri, Cole, Fausel, Chuop & Mace, 2016), recently published the result of their study which concluded that: “Surgical release of tongue-tie/lip-tie results in significant improvement in breastfeeding outcomes”. Can you elucidate upon the study design and its findings?

Pamela Douglas: Pre-post surveys, such as Ghaheri et al’s 2016 study, are notoriously methodologically weak and prone to interpretive bias.14

Renee Kam: Research about the efficacy of releasing ULTs to improve breastfeeding outcomes is seriously lacking. There is no reliable assessment tool for upper lip-tie and a lack of evidence to support the efficacy of a frenotomy of labial frenula in breastfed babies. The few studies which have included ULT release have either included very small numbers of babies having upper lip-tie releases or have included babies having a release upper lip ties and tongue ties at the same time, making it impossible to know if any improvements were due to the tongue-tie release, upper lip-tie release or both. Here, to answer your previous question, to date, no research has looked into the treatment of buccal ties for breastfeeding outcomes.

There are various classification scales for labial frenulums such as the Kotlow scale. The title of this scale is misleading as it contains the word ‘tie’. Hence it can give some people the incorrect assumption that a class III or IV labial frenulum is somehow a problem. What this scale actually shows is the normal range of insertion sites for a labial frenulum. And, in normal cases, the vast majority of babies’ labial frenulums insert low down on the upper gum (class III) or even wrap around it (class IV). It’s important to note that, for effective breastfeeding, the upper lip does not have to flange out in order to create a seal. It just has to rest in a neutral position — not flanged out, not tucked in.

Lois Wattis: I entirely agree with Renee’s view about the neutrality of the upper lip, including the labial frenulum, in relation to latch for breastfeeding. Even babies with asymmetrical facial features, cleft lips and other permanent and temporary anomalies only need to achieve a seal with the upper lip to breastfeed successfully.

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you for that. In addition to studies on tongue tie revisions and breastfeeding outcomes, there has been an increase in studies, specifically Kotlow (2016) and Siegel (2016), which claimed that surgical intervention improves outcomes for acid reflux and aerophagia in babies”. Can you discuss these studies design and findings?

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you for that. In addition to studies on tongue tie revisions and breastfeeding outcomes, there has been an increase in studies, specifically Kotlow (2016) and Siegel (2016), which claimed that surgical intervention improves outcomes for acid reflux and aerophagia in babies”. Can you discuss these studies design and findings?

Renee Kam: The AIR hypothesis has led to reflux being used as another reason to diagnose the oral anatomic abnormalities in infants in the presence of breastfeeding problems. More research with objective indicators and less vested interest is needed in this area. A thorough understanding of normal infant behavior and feeding problems which aren’t tie related are also imperative before any conclusions about AIR can be reached.

Tatyana Elleseff: One final question, colleagues are you aware of any studies which describe long-term outcomes of surgical interventions for tongue ties?

Pamela Douglas: The systematic reviews note that there is a lack of evidence demonstrating long-term outcomes of surgical interventions.

Tatyana Elleseff: Thank you for such informative discussion, colleagues.

There you have it, readers. Both research and clinical practice align to indicate that:

There you have it, readers. Both research and clinical practice align to indicate that:

- There’s significant normal variation when it comes to most anatomical structures including the frenulum

- Just because a child presents with restricted frenulum does not automatically imply adverse feeding as well as speech outcomes and immediately necessitates a tongue tie release

- When breastfeeding difficulties arise, in the presence of restricted frenulum, it is very important to involve an experienced lactation specialist who will perform a differential diagnosis in order to determine the source of the baby’s true breastfeeding difficulties

Now, I’d like to take a moment and address the myth of tongue ties affecting speech production, which continues to persist among speech-language pathologists despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

For that purpose, I will use excerpts from an excellent ASHA Leader December 2005 article written by an esteemed Dr. Kummer who is certainly well qualified to discuss this issue. According to Dr. Kummer, “there is no empirical evidence in the literature that ankyloglossia typically causes speech defects. On the contrary, several authors, even from decades ago, have disputed the belief that there is a strong causal relationship (Wallace, 1963; Block, 1968; Catlin & De Haan, 1971; Wright, 1995; Agarwal & Raina, 2003).”

Since many children with restricted frenulum do not have any speech production difficulties, Dr Kummer explains why that is the case by discussing the effect of tongue tip positioning for speech production.

Since many children with restricted frenulum do not have any speech production difficulties, Dr Kummer explains why that is the case by discussing the effect of tongue tip positioning for speech production.

“Lingual-alveolar sounds (t, d, n) are produced with the top of the tongue tip and therefore, they can be produced with very little tongue elevation or mobility.

The /s/ and /z/ sounds require the tongue tip to be elevated only slightly but can be produced with little distortion if the tip is down.

The most the tongue tip needs to elevate is to the alveolar ridge for the production of an /l/. However, this sound can actually be produced with the tongue tip down and the dorsum of the tongue up against the alveolar ridge. Even an /r/ sound can be produced with the tongue tip down as long as the back of the tongue is elevated on both sides.

The most the tongue needs to protrude is to the back of the maxillary incisors for the production of /th/. All of these sounds can usually be produced, even with significant tongue tip restriction. This can be tested by producing these sounds with the tongue tip pressed down or against the mandibular gingiva. This results in little, if any, distortion.” (Kummer, 2005, ASHA Leader)

In 2009, Dr. Sharynne McLeod, did research on electropalatography of speech sounds with adults. Her findings (below) which are coronal images of tongue positioning including bracing, lateral contact and groove formation for consonants support the above information provided by Dr. Kummer.

Once again research and clinical practice align to indicate that there’s insufficient evidence to indicate the effect of restricted frenulum on the production of speech sounds.

Finally, I would like to conclude this post with a list of links from recent systematic reviews summarizing the latest research on this topic.

Ankyloglossia/Tongue Tie Systematic Review Summaries to Date (2017):

- A small body of evidence suggests that frenotomy may be associated with mother reported improvements in breastfeeding, and potentially in nipple pain, but with small, short-term studies with inconsistent methodology, the strength of the evidence is low to insufficient.

- In an infant with tongue-tie and feeding difficulties, surgical release of the tongue-tie does not consistently improve infant feeding but is likely to improve maternal nipple pain. Further research is needed to clarify and confirm this effect.

- Data are currently insufficient for assessing the effects of frenotomy on nonbreastfeeding outcomes that may be associated with ankyloglossia

- Given the lack of good-quality studies and limitations in the measurement of outcomes, we considered the strength of the evidence for the effect of surgical interventions to improve speech and articulation to be insufficient.

- Large temporal increases and substantial spatial variations in ankyloglossia and frenotomy rates were observed that may indicate a diagnostic suspicion bias and increasing use of a potentially unnecessary surgical procedure among infants.

References

- Power R, Murphy J. Tongue-tie and frenotomy in infants with breastfeeding difficulties: achieving a balance. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2015;100:489-494.

- Francis DO, Krishnaswami S, McPheeters M. Treatment of ankyloglossia and breastfeeding outcomes: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2015;135(6):e1467-e1474.

- O’Shea JE, Foster JP, O’Donnell CPF, Breathnach D, Jacobs SE, Todd DA, et al. Frenotomy for tongue-tie in newborn infants (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (3):Art. No.:CD011065.

- Hall D, Renfrew M. Tongue tie. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2005;90:1211-1215.

- Coryllos E, Watson Genna C, Salloum A. Congenital tongue-tie and its impact on breastfeeding. Breastfeeding: Best for Mother and Baby, American Academy of Pediatrics. 2004 Summer:1-6.

- Coryllos EV, Watson Genna C, LeVan Fram J. Minimally Invasive Treatment for Posterior Tongue-Tie (The Hidden Tongue-Tie). In: Watson Genna C, editor. Supporting Sucking Skills. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2013. p. 243-251.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. Infant feeding guidelines: information for health workers. In: Government A, editor. 2012. p. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/guidelines-publications/n56.

- Watson Genna C, editor. Supporting sucking skills in breastfeeding infants. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2016.

- Griffiths DM. Do tongue ties affect breastfeeding? . Journal of Human Lactation. 2004;20:411.

- Ricke L, Baker N, Madlon-Kay D. Newborn tongue-tie: prevalence and effect on breastfeeding. Journal of American Board of Family Practice. 2005;8:1-8.

- Madlon-Kay D, Ricke L, Baker N, DeFor TA. Case series of 148 tongue-tied newborn babies evaluated with the assessment tool for lingual function. Midwifery. 2008;24:353-357.

- Ballard JL, Auer CE, Khoury JC. Ankyloglossia: assessment, incidence, and effect of frenuloplasty on the breastfeeding dyad. Pediatrics. 2002;110:e63.

- Amir L, James JP, Donath SM. Reliability of the Hazelbaker Assessment Tool for Lingual Frenulum Function. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2006;1:3.

- Douglas PS. Conclusions of Ghaheri’s study that laser surgery for posterior tongue and lip ties improve breastfeeding are not substantiated. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2017;12(3):DOI: 10.1089/bfm.2017.0008.

Author Bios (in alphabetical order):

Dr. Pamela Douglas is the founder of a charitable organization, the Possums Clinic, a general practitioner since 1987, an IBCLC (1994-2004; 2012-Present) and researcher. She is an Associate Professor (Adjunct) with the Centre for Health Practice Innovation, Griffith University, and a Senior Lecturer with the Discipline of General Practice, The University of Queensland. Pam enjoys working clinically with families across the spectrum of challenges in early life, many complex (including breastfeeding difficulty) unsettled infant behaviors, reflux, allergies, tongue-tie/oral connective tissue problems, and gut problems. She is author of The discontented little baby book: all you need to know about feeds, sleep and crying (UQP) www.possumsonline.com; www.pameladouglas.com.au

Dr. Pamela Douglas is the founder of a charitable organization, the Possums Clinic, a general practitioner since 1987, an IBCLC (1994-2004; 2012-Present) and researcher. She is an Associate Professor (Adjunct) with the Centre for Health Practice Innovation, Griffith University, and a Senior Lecturer with the Discipline of General Practice, The University of Queensland. Pam enjoys working clinically with families across the spectrum of challenges in early life, many complex (including breastfeeding difficulty) unsettled infant behaviors, reflux, allergies, tongue-tie/oral connective tissue problems, and gut problems. She is author of The discontented little baby book: all you need to know about feeds, sleep and crying (UQP) www.possumsonline.com; www.pameladouglas.com.au

Renee Kam qualified with a Bachelor of Physiotherapy from the University of Melbourne in 2000. She then worked as a physiotherapist for 6 years, predominantly in the areas of women’s health, pediatric and musculoskeletal physiotherapy. She became an Australian Breastfeeding Association Breastfeeding (ABA) counselor in 2010 and obtained the credential of International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC) in 2012. In 2013, Renee’s book, The Newborn Baby Manual, was published which covers the topics that Renee is passionate about; breastfeeding, baby sleep and baby behavior. These days, Renee spends most of her time being a mother to her two young daughters, writing breastfeeding content for BellyBelly.com.au, fulfilling her role as national breastfeeding information manager with ABA and working as an IBCLC in private practice and at a private hospital in Melbourne, Australia.

Renee Kam qualified with a Bachelor of Physiotherapy from the University of Melbourne in 2000. She then worked as a physiotherapist for 6 years, predominantly in the areas of women’s health, pediatric and musculoskeletal physiotherapy. She became an Australian Breastfeeding Association Breastfeeding (ABA) counselor in 2010 and obtained the credential of International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC) in 2012. In 2013, Renee’s book, The Newborn Baby Manual, was published which covers the topics that Renee is passionate about; breastfeeding, baby sleep and baby behavior. These days, Renee spends most of her time being a mother to her two young daughters, writing breastfeeding content for BellyBelly.com.au, fulfilling her role as national breastfeeding information manager with ABA and working as an IBCLC in private practice and at a private hospital in Melbourne, Australia.

Lois Wattis is a Registered Nurse/Midwife, International Board Certified Lactation Consultant and Fellow of the Australian College of Midwives. Working in both hospital and community settings, Lois has enhanced her midwifery skills and expertise by providing women-centred care to thousands of mothers and babies, including more than 50 women who chose to give birth at home. Lois’ qualifications include Bachelor of Nursing Degree (Edith Cowan University, Perth WA), Post Graduate Diploma in Clinical Nursing, Midwifery (Curtin University, Perth WA), accreditation as Independent Practising Midwife by the Australian College of Midwives in 2002 and International Board Certified Lactation Consultant in 2004. Lois was inducted as a Fellow of the Australian College of Midwives (FACM) in 2005 in recognition of her services to women and midwifery in Australia. Lois has authored numerous articles which have been published internationally in parenting and midwifery journals, and shares her broad experience via her creations “New Baby 101” book, smartphone App, on-line videos and Facebook page. www.newbaby101.com.au Lois has worked for the past 10 years in Qld, Australia in a dedicated Lactation Consultant role as well as in private practice www.birthjourney.com

Lois Wattis is a Registered Nurse/Midwife, International Board Certified Lactation Consultant and Fellow of the Australian College of Midwives. Working in both hospital and community settings, Lois has enhanced her midwifery skills and expertise by providing women-centred care to thousands of mothers and babies, including more than 50 women who chose to give birth at home. Lois’ qualifications include Bachelor of Nursing Degree (Edith Cowan University, Perth WA), Post Graduate Diploma in Clinical Nursing, Midwifery (Curtin University, Perth WA), accreditation as Independent Practising Midwife by the Australian College of Midwives in 2002 and International Board Certified Lactation Consultant in 2004. Lois was inducted as a Fellow of the Australian College of Midwives (FACM) in 2005 in recognition of her services to women and midwifery in Australia. Lois has authored numerous articles which have been published internationally in parenting and midwifery journals, and shares her broad experience via her creations “New Baby 101” book, smartphone App, on-line videos and Facebook page. www.newbaby101.com.au Lois has worked for the past 10 years in Qld, Australia in a dedicated Lactation Consultant role as well as in private practice www.birthjourney.com

A Focus on Literacy

In recent months, I have been focusing more and more on speaking engagements as well as the development of products with an explicit focus on assessment and intervention of literacy in speech-language pathology. Today I’d like to introduce 4 of my recently developed products pertinent to assessment and treatment of literacy in speech-language pathology.

In recent months, I have been focusing more and more on speaking engagements as well as the development of products with an explicit focus on assessment and intervention of literacy in speech-language pathology. Today I’d like to introduce 4 of my recently developed products pertinent to assessment and treatment of literacy in speech-language pathology.

First up is the Comprehensive Assessment and Treatment of Literacy Disorders in Speech-Language Pathology

First up is the Comprehensive Assessment and Treatment of Literacy Disorders in Speech-Language Pathology

which describes how speech-language pathologists can effectively assess and treat children with literacy disorders, (reading, spelling, and writing deficits including dyslexia) from preschool through adolescence. It explains the impact of language disorders on literacy development, lists formal and informal assessment instruments and procedures, as well as describes the importance of assessing higher order language skills for literacy purposes. It reviews components of effective reading instruction including phonological awareness, orthographic knowledge, vocabulary awareness, morphological awareness, as well as reading fluency and comprehension. Finally, it provides recommendations on how components of effective reading instruction can be cohesively integrated into speech-language therapy sessions in order to improve literacy abilities of children with language disorders and learning disabilities.

Next up is a product entitled From Wordless Picture Books to Reading Instruction: Effective Strategies for SLPs Working with Intellectually Impaired Students. This product discusses how to address the development of critical thinking skills through a variety of picture books utilizing the framework outlined in Bloom’s Taxonomy: Cognitive Domain which encompasses the categories of knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation in children with intellectual impairments. It shares a number of similarities with the above product as it also reviews components of effective reading instruction for children with language and intellectual disabilities as well as provides recommendations on how to integrate reading instruction effectively into speech-language therapy sessions.