Two years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “What’s Memes Got To Do With It?” which summarized key points of Dr. Alan G. Kamhi’s 2004 article: “A Meme’s Eye View of Speech-Language Pathology“. It delved into answering the following question: “Why do some terms, labels, ideas, and constructs [in our field] prevail whereas others fail to gain acceptance?”.

Two years ago I wrote a blog post entitled: “What’s Memes Got To Do With It?” which summarized key points of Dr. Alan G. Kamhi’s 2004 article: “A Meme’s Eye View of Speech-Language Pathology“. It delved into answering the following question: “Why do some terms, labels, ideas, and constructs [in our field] prevail whereas others fail to gain acceptance?”.

Today I would like to reference another article by Dr. Kamhi written in 2014, entitled “Improving Clinical Practices for Children With Language and Learning Disorders“.

This article was written to address the gaps between research and clinical practice with respect to the implementation of EBP for intervention purposes.

Dr. Kamhi begins the article by posing 10 True or False questions for his readers:

- Learning is easier than generalization.

- Instruction that is constant and predictable is more effective than instruction that varies the conditions of learning and practice.

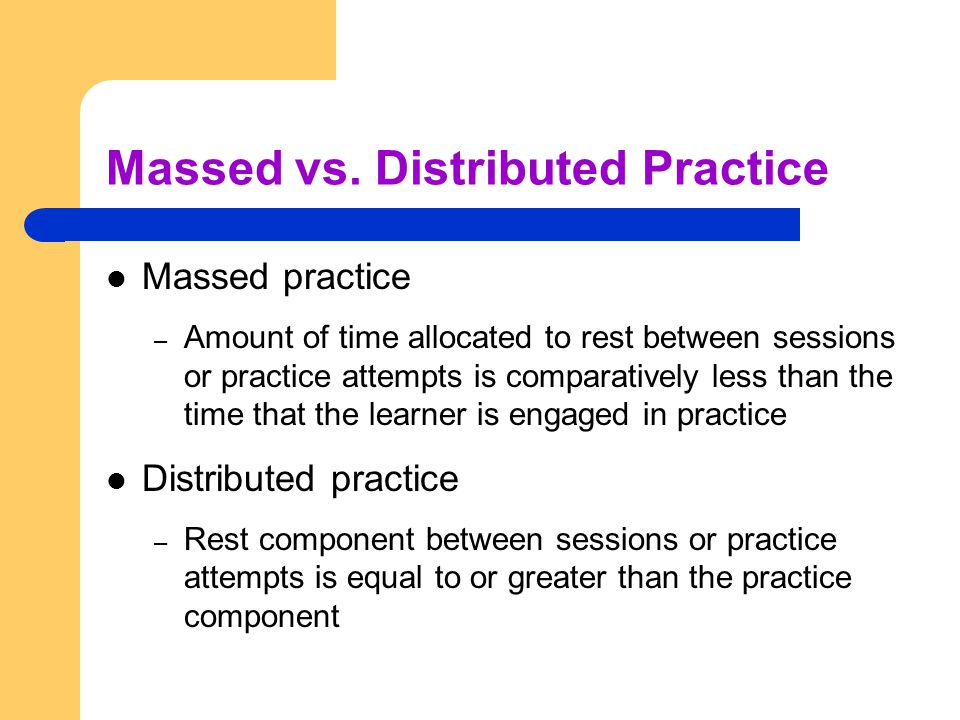

- Focused stimulation (massed practice) is a more effective teaching strategy than varied stimulation (distributed practice).

- The more feedback, the better.

- Repeated reading of passages is the best way to learn text information.

- More therapy is always better.

- The most effective language and literacy interventions target processing limitations rather than knowledge deficits.

- Telegraphic utterances (e.g., push ball, mommy sock) should not be provided as input for children with limited language.

- Appropriate language goals include increasing levels of mean length of utterance (MLU) and targeting Brown’s (1973) 14 grammatical morphemes.

- Sequencing is an important skill for narrative competence.

Guess what? Only statement 8 of the above quiz is True! Every other statement from the above is FALSE!

Now, let’s talk about why that is!

First up is the concept of learning vs. generalization. Here Dr. Kamhi discusses that some clinicians still possess an “outdated behavioral view of learning” in our field, which is not theoretically and clinically useful. He explains that when we are talking about generalization – what children truly have a difficulty with is “transferring narrow limited rules to new situations“. “Children with language and learning problems will have difficulty acquiring broad-based rules and modifying these rules once acquired, and they also will be more vulnerable to performance demands on speech production and comprehension (Kamhi, 1988)” (93). After all, it is not “reasonable to expect children to use language targets consistently after a brief period of intervention” and while we hope that “language intervention [is] designed to lead children with language disorders to acquire broad-based language rules” it is a hugely difficult task to undertake and execute.

First up is the concept of learning vs. generalization. Here Dr. Kamhi discusses that some clinicians still possess an “outdated behavioral view of learning” in our field, which is not theoretically and clinically useful. He explains that when we are talking about generalization – what children truly have a difficulty with is “transferring narrow limited rules to new situations“. “Children with language and learning problems will have difficulty acquiring broad-based rules and modifying these rules once acquired, and they also will be more vulnerable to performance demands on speech production and comprehension (Kamhi, 1988)” (93). After all, it is not “reasonable to expect children to use language targets consistently after a brief period of intervention” and while we hope that “language intervention [is] designed to lead children with language disorders to acquire broad-based language rules” it is a hugely difficult task to undertake and execute.

Next, Dr. Kamhi addresses the issue of instructional factors, specifically the importance of “varying conditions of instruction and practice“. Here, he addresses the fact that while contextualized instruction is highly beneficial to learners unless we inject variability and modify various aspects of instruction including context, composition, duration, etc., we ran the risk of limiting our students’ long-term outcomes.

After that, Dr. Kamhi addresses the concept of distributed practice (spacing of intervention) and how important it is for teaching children with language disorders. He points out that a number of recent studies have found that “spacing and distribution of teaching episodes have more of an impact on treatment outcomes than treatment intensity” (94).

After that, Dr. Kamhi addresses the concept of distributed practice (spacing of intervention) and how important it is for teaching children with language disorders. He points out that a number of recent studies have found that “spacing and distribution of teaching episodes have more of an impact on treatment outcomes than treatment intensity” (94).

He also advocates reducing evaluative feedback to learners to “enhance long-term retention and generalization of motor skills“. While he cites research from studies pertaining to speech production, he adds that language learning could also benefit from this practice as it would reduce conversational disruptions and tunning out on the part of the student.

From there he addresses the limitations of repetition for specific tasks (e.g., text rereading). He emphasizes how important it is for students to recall and retrieve text rather than repeatedly reread it (even without correction), as the latter results in a lack of comprehension/retention of read information.

After that, he discusses treatment intensity. Here he emphasizes the fact that higher dose of instruction will not necessarily result in better therapy outcomes due to the research on the effects of “learning plateaus and threshold effects in language and literacy” (95). We have seen research on this with respect to joint book reading, vocabulary words exposure, etc. As such, at a certain point in time increased intensity may actually result in decreased treatment benefits.

His next point against processing interventions is very near and dear to my heart. Those of you familiar with my blog know that I have devoted a substantial number of posts pertaining to the lack of validity of CAPD diagnosis (as a standalone entity) and urged clinicians to provide language based vs. specific auditory interventions which lack treatment utility. Here, Dr. Kamhi makes a great point that: “Interventions that target processing skills are particularly appealing because they offer the promise of improving language and learning deficits without having to directly target the specific knowledge and skills required to be a proficient speaker, listener, reader, and writer.” (95) The problem is that we have numerous studies on the topic of improvement of isolated skills (e.g., auditory skills, working memory, slow processing, etc.) which clearly indicate lack of effectiveness of these interventions. As such, “practitioners should be highly skeptical of interventions that promise quick fixes for language and learning disabilities” (96).

His next point against processing interventions is very near and dear to my heart. Those of you familiar with my blog know that I have devoted a substantial number of posts pertaining to the lack of validity of CAPD diagnosis (as a standalone entity) and urged clinicians to provide language based vs. specific auditory interventions which lack treatment utility. Here, Dr. Kamhi makes a great point that: “Interventions that target processing skills are particularly appealing because they offer the promise of improving language and learning deficits without having to directly target the specific knowledge and skills required to be a proficient speaker, listener, reader, and writer.” (95) The problem is that we have numerous studies on the topic of improvement of isolated skills (e.g., auditory skills, working memory, slow processing, etc.) which clearly indicate lack of effectiveness of these interventions. As such, “practitioners should be highly skeptical of interventions that promise quick fixes for language and learning disabilities” (96).

Now let us move on to language and particularly the models we provide to our clients to encourage greater verbal output. Research indicates that when clinicians are attempting to expand children’s utterances, they need to provide well-formed language models. Studies show that children select strong input when its surrounded by weaker input (the surrounding weaker syllables make stronger syllables stand out). As such, clinicians should expand upon/comment on what clients are saying with grammatically complete models vs. telegraphic productions.

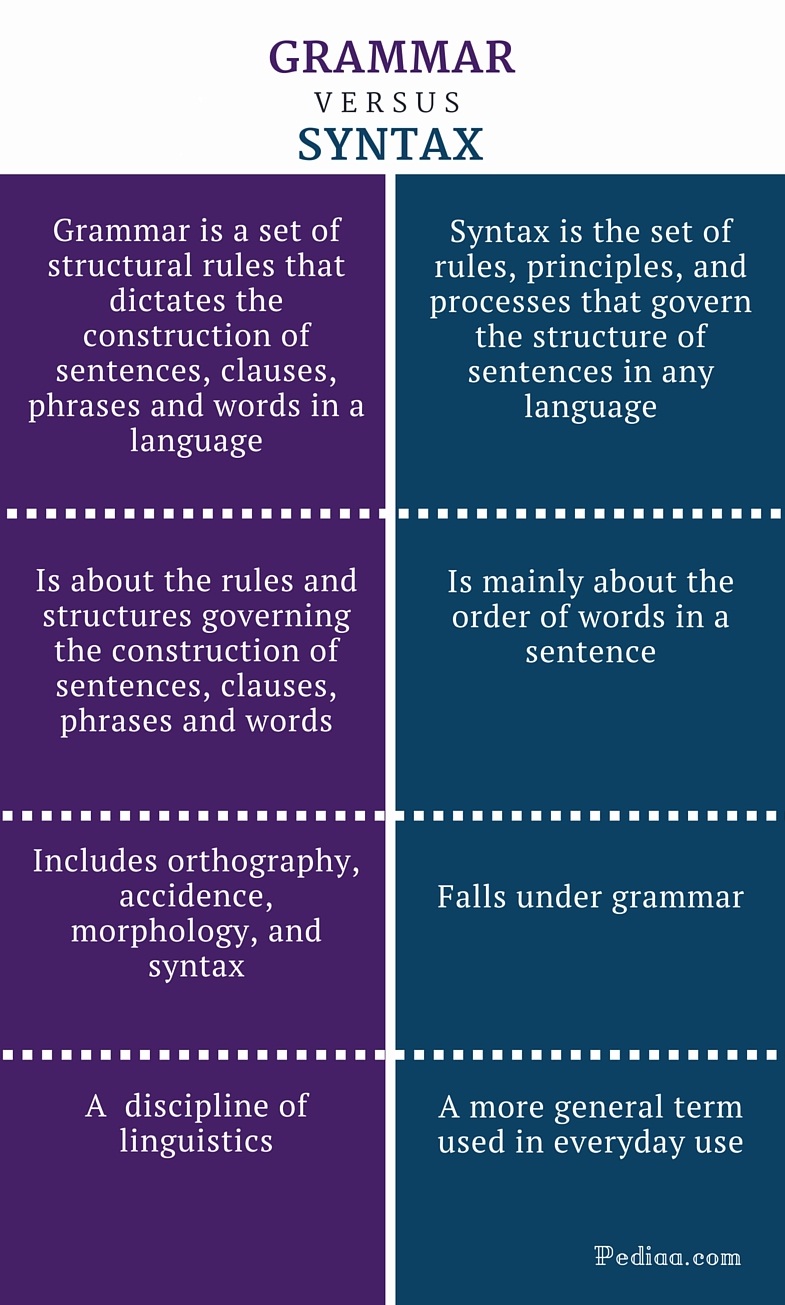

From there lets us take a look at Dr. Kamhi’s recommendations for grammar and syntax. Grammatical development goes much further than addressing Brown’s morphemes in therapy and calling it a day. As such, it is important to understand that children with developmental language disorders (DLD) (#DevLang) do not have difficulty acquiring all morphemes. Rather studies have shown that they have difficulty learning grammatical morphemes that reflect tense and agreement (e.g., third-person singular, past tense, auxiliaries, copulas, etc.). As such, use of measures developed by Hadley & Holt, 2006; Hadley & Short, 2005 (e.g., Tense Marker Total & Productivity Score) can yield helpful information regarding which grammatical structures to target in therapy.

From there lets us take a look at Dr. Kamhi’s recommendations for grammar and syntax. Grammatical development goes much further than addressing Brown’s morphemes in therapy and calling it a day. As such, it is important to understand that children with developmental language disorders (DLD) (#DevLang) do not have difficulty acquiring all morphemes. Rather studies have shown that they have difficulty learning grammatical morphemes that reflect tense and agreement (e.g., third-person singular, past tense, auxiliaries, copulas, etc.). As such, use of measures developed by Hadley & Holt, 2006; Hadley & Short, 2005 (e.g., Tense Marker Total & Productivity Score) can yield helpful information regarding which grammatical structures to target in therapy.

With respect to syntax, Dr. Kamhi notes that many clinicians erroneously believe that complex syntax should be targeted when children are much older. The Common Core State Standards do not help this cause further, since according to the CCSS complex syntax should be targeted 2-3 grades, which is far too late. Typically developing children begin developing complex syntax around 2 years of age and begin readily producing it around 3 years of age. As such, clinicians should begin targeting complex syntax in preschool years and not wait until the children have mastered all morphemes and clauses (97)

Finally, Dr. Kamhi wraps up his article by offering suggestions regarding prioritizing intervention goals. Here, he explains that goal prioritization is affected by

- clinician experience and competencies

- the degree of collaboration with other professionals

- type of service delivery model

- client/student factors

He provides a hypothetical case scenario in which the teaching responsibilities are divvied up between three professionals, with SLP in charge of targeting narrative discourse. Here, he explains that targeting narratives does not involve targeting sequencing abilities. “The ability to understand and recall events in a story or script depends on conceptual understanding of the topic and attentional/memory abilities, not sequencing ability.” He emphasizes that sequencing is not a distinct cognitive process that requires isolated treatment. Yet many SLPs “continue to believe that sequencing is a distinct processing skill that needs to be assessed and treated.” (99)

Dr. Kamhi supports the above point by providing an example of two passages. One, which describes a random order of events, and another which follows a logical order of events. He then points out that the randomly ordered story relies exclusively on attention and memory in terms of “sequencing”, while the second story reduces demands on memory due to its logical flow of events. As such, he points out that retelling deficits seemingly related to sequencing, tend to be actually due to “limitations in attention, working memory, and/or conceptual knowledge“. Hence, instead of targeting sequencing abilities in therapy, SLPs should instead use contextualized language intervention to target aspects of narrative development (macro and microstructural elements).

Dr. Kamhi supports the above point by providing an example of two passages. One, which describes a random order of events, and another which follows a logical order of events. He then points out that the randomly ordered story relies exclusively on attention and memory in terms of “sequencing”, while the second story reduces demands on memory due to its logical flow of events. As such, he points out that retelling deficits seemingly related to sequencing, tend to be actually due to “limitations in attention, working memory, and/or conceptual knowledge“. Hence, instead of targeting sequencing abilities in therapy, SLPs should instead use contextualized language intervention to target aspects of narrative development (macro and microstructural elements).

Furthermore, here it is also important to note that the “sequencing fallacy” affects more than just narratives. It is very prevalent in the intervention process in the form of the ubiquitous “following directions” goal/s. Many clinicians readily create this goal for their clients due to their belief that it will result in functional therapeutic language gains. However, when one really begins to deconstruct this goal, one will realize that it involves a number of discrete abilities including: memory, attention, concept knowledge, inferencing, etc. Consequently, targeting the above goal will not result in any functional gains for the students (their memory abilities will not magically improve as a result of it). Instead, targeting specific language and conceptual goals (e.g., answering questions, producing complex sentences, etc.) and increasing the students’ overall listening comprehension and verbal expression will result in improvements in the areas of attention, memory, and processing, including their ability to follow complex directions.

There you have it! Ten practical suggestions from Dr. Kamhi ready for immediate implementation! And for more information, I highly recommend reading the other articles in the same clinical forum, all of which possess highly practical and relevant ideas for therapeutic implementation. They include:

There you have it! Ten practical suggestions from Dr. Kamhi ready for immediate implementation! And for more information, I highly recommend reading the other articles in the same clinical forum, all of which possess highly practical and relevant ideas for therapeutic implementation. They include:

- Clinical Scientists Improving Clinical Practices: In Thoughts and Actions

- Approaching Early Grammatical Intervention From a Sentence-Focused Framework

- What Works in Therapy: Further Thoughts on Improving Clinical Practice for Children With Language Disorders

- Improving Clinical Practice: A School-Age and School-Based Perspective

- Improving Clinical Services: Be Aware of Fuzzy Connections Between Principles and Strategies

- One Size Does Not Fit All: Improving Clinical Practice in Older Children and Adolescents With Language and Learning Disorders

- Language Intervention at the Middle School: Complex Talk Reflects Complex Thought

- Using Our Knowledge of Typical Language Development

References:

Kamhi, A. (2014). Improving clinical practices for children with language and learning disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 45(2), 92-103

Helpful Social Media Resources:

I’ve always loved fairy tales! Much like Audrey Hepburn “If I’m honest I have to tell you I still read fairy-tales and I like them best of all.” Not to compare myself with Einstein (sadly in any way, sigh) but “When I examine myself and my methods of thought, I come to the conclusion that the gift of fantasy has meant more to me than any talent for abstract, positive thinking.”

I’ve always loved fairy tales! Much like Audrey Hepburn “If I’m honest I have to tell you I still read fairy-tales and I like them best of all.” Not to compare myself with Einstein (sadly in any way, sigh) but “When I examine myself and my methods of thought, I come to the conclusion that the gift of fantasy has meant more to me than any talent for abstract, positive thinking.” Today I want to talk treatment. That thing that we need to plan for as we are doing our assessments. But are we starting our treatments the right way? The answer may surprise you. I often see SLPs phrasing questions regarding treatment the following way: “I have a student diagnosed with ____ (insert disorder here). What is everyone using (program/app/materials) during therapy sessions to address ___ diagnosis?”

Today I want to talk treatment. That thing that we need to plan for as we are doing our assessments. But are we starting our treatments the right way? The answer may surprise you. I often see SLPs phrasing questions regarding treatment the following way: “I have a student diagnosed with ____ (insert disorder here). What is everyone using (program/app/materials) during therapy sessions to address ___ diagnosis?” There could be endless variations of how deficits manifest in poor readers. Is it aspects of phonological awareness, phonics, morphology, etc. What combination of deficits is preventing the child from becoming a good reader?

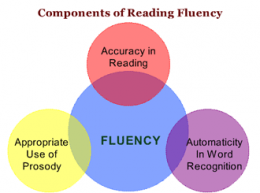

There could be endless variations of how deficits manifest in poor readers. Is it aspects of phonological awareness, phonics, morphology, etc. What combination of deficits is preventing the child from becoming a good reader? Reading Fluency: “LG’s reading fluency during this task was judged to be significantly affected by excessive speed, inappropriate pausing, word misreadings, choppy prosody, as well as inefficient word attack skills. While she was able to limitedly utilize the phonetic spelling of unfamiliar words (e.g., __) provided to her in parenthesis next to the word (which she initially misread as ‘__’), she exhibited limited use of metalinguistic strategies (e.g., pre-scanning sentences to aid text comprehension, self-correcting to ensure that the read words made sense in the context of the sentence, etc.), when reading the provided passage. To illustrate, during the reading of the text, LG was observed to frequently (at least 3 times) lose her place and skip entire lines of text without any attempts at self-correction. At times she was observed to read the same word a number of different ways (e.g., read ‘soup’ as ‘soup’ then as ‘soap’, ‘roots’ as ‘roofs’ then as ‘roots’, etc.) without attempting to self-correct. LG’s oral reading rate was also observed to be impaired for her age/grade levels. Her prosody was significantly adversely affected due to lack of adequate pausing for punctuation marks (e.g., periods, commas, etc.). Instead, she paused during text reading only when he could not decode select words in the text. Though, LG was able to read 70 words per minute, which was judged to be grossly commensurate with grade-level, out of these 70 words she skipped 2 entire lines of text, invented an entire line of text, as well as made 4 decoding errors and 6 inappropriate pauses.”

Reading Fluency: “LG’s reading fluency during this task was judged to be significantly affected by excessive speed, inappropriate pausing, word misreadings, choppy prosody, as well as inefficient word attack skills. While she was able to limitedly utilize the phonetic spelling of unfamiliar words (e.g., __) provided to her in parenthesis next to the word (which she initially misread as ‘__’), she exhibited limited use of metalinguistic strategies (e.g., pre-scanning sentences to aid text comprehension, self-correcting to ensure that the read words made sense in the context of the sentence, etc.), when reading the provided passage. To illustrate, during the reading of the text, LG was observed to frequently (at least 3 times) lose her place and skip entire lines of text without any attempts at self-correction. At times she was observed to read the same word a number of different ways (e.g., read ‘soup’ as ‘soup’ then as ‘soap’, ‘roots’ as ‘roofs’ then as ‘roots’, etc.) without attempting to self-correct. LG’s oral reading rate was also observed to be impaired for her age/grade levels. Her prosody was significantly adversely affected due to lack of adequate pausing for punctuation marks (e.g., periods, commas, etc.). Instead, she paused during text reading only when he could not decode select words in the text. Though, LG was able to read 70 words per minute, which was judged to be grossly commensurate with grade-level, out of these 70 words she skipped 2 entire lines of text, invented an entire line of text, as well as made 4 decoding errors and 6 inappropriate pauses.”

Today I am writing my last installment in the five-part early intervention assessment series. My

Today I am writing my last installment in the five-part early intervention assessment series. My

Spoon Stripping and Mouth Closure: During the yogurt presentation, AK’s spoon stripping abilities and mouth closure were deemed good (adequate) when fed by a caregiver and fair when AK fed self (incomplete food stripping from the spoon was observed due to only partial mouth closure). According to parental report, AK’s spoon stripping abilities have improved in recent months. Ms. K was observed to present spoon upwardly in AK’s mouth and hold it still until AK placed her lips firmly around the spoon and initiated spoon stripping. Since this strategy is working adequately for all parties in question no further recommendations regarding spoon feeding are necessary at this time. Skill monitoring is recommended on an ongoing basis for further refinement.

Spoon Stripping and Mouth Closure: During the yogurt presentation, AK’s spoon stripping abilities and mouth closure were deemed good (adequate) when fed by a caregiver and fair when AK fed self (incomplete food stripping from the spoon was observed due to only partial mouth closure). According to parental report, AK’s spoon stripping abilities have improved in recent months. Ms. K was observed to present spoon upwardly in AK’s mouth and hold it still until AK placed her lips firmly around the spoon and initiated spoon stripping. Since this strategy is working adequately for all parties in question no further recommendations regarding spoon feeding are necessary at this time. Skill monitoring is recommended on an ongoing basis for further refinement.  Cup and Straw Drinking: AK was also observed to drink 40 mls of water from a cup given parental assistance. Minor anterior spillage was intermittently noted during liquid intake. It is recommended that the parents modify cup presentation by providing AK with a plastic cup with two handles on each side, which would improve her ability to grasp and maintain hold on cup while drinking.

Cup and Straw Drinking: AK was also observed to drink 40 mls of water from a cup given parental assistance. Minor anterior spillage was intermittently noted during liquid intake. It is recommended that the parents modify cup presentation by providing AK with a plastic cup with two handles on each side, which would improve her ability to grasp and maintain hold on cup while drinking. As SLPs we routinely administer a variety of testing batteries in order to assess our students’ speech-language abilities. Grammar, syntax, vocabulary, and sentence formulation get frequent and thorough attention. But how about narrative production? Does it get its fair share of attention when the clinicians are looking to determine the extent of the child’s language deficits? I was so curious about what the clinicians across the country were doing that in 2013, I created a survey and posted a link to it in several SLP-related FB groups. I wanted to find out how many SLPs were performing narrative assessments, in which settings, and with which populations. From those who were performing these assessments, I wanted to know what type of assessments were they using and how they were recording and documenting their findings. Since the purpose of this survey was non-research based (I wasn’t planning on submitting a research manuscript with my findings), I only analyzed the first 100 responses (the rest were very similar in nature) which came my way, in order to get the general flavor of current trends among clinicians, when it came to narrative assessments. Here’s a brief overview of my [limited] findings.

As SLPs we routinely administer a variety of testing batteries in order to assess our students’ speech-language abilities. Grammar, syntax, vocabulary, and sentence formulation get frequent and thorough attention. But how about narrative production? Does it get its fair share of attention when the clinicians are looking to determine the extent of the child’s language deficits? I was so curious about what the clinicians across the country were doing that in 2013, I created a survey and posted a link to it in several SLP-related FB groups. I wanted to find out how many SLPs were performing narrative assessments, in which settings, and with which populations. From those who were performing these assessments, I wanted to know what type of assessments were they using and how they were recording and documenting their findings. Since the purpose of this survey was non-research based (I wasn’t planning on submitting a research manuscript with my findings), I only analyzed the first 100 responses (the rest were very similar in nature) which came my way, in order to get the general flavor of current trends among clinicians, when it came to narrative assessments. Here’s a brief overview of my [limited] findings.  In this post, I am continuing my series of articles on speech and language assessments of children under 3 years of age. My first installment in this series offered suggestions regarding what information to include in

In this post, I am continuing my series of articles on speech and language assessments of children under 3 years of age. My first installment in this series offered suggestions regarding what information to include in  As mentioned in my previous post on

As mentioned in my previous post on  Developmental Milestones expected of a 16-18 months old toddler:

Developmental Milestones expected of a 16-18 months old toddler:  Play Skills/Routines:

Play Skills/Routines: Materials to use with the child to promote language and play:

Materials to use with the child to promote language and play:  Core vocabulary categories for listening and speaking:

Core vocabulary categories for listening and speaking:

Prior to being reevaluated by me, TQ underwent an early intervention assessment at ~26 months of age. She was diagnosed with CAS by an evaluating SLP and was found to be eligible for speech-language services, which she began receiving shortly thereafter. However, Mrs. Q noted that TQ was making very few gains in therapy and her treating SLP was uncertain regarding why her progress in therapy was so limited. Mrs. Q was also rather uncertain that TQ’s diagnosis of CAS was indeed a correct one, which was another reason why she sought a second opinion.

Prior to being reevaluated by me, TQ underwent an early intervention assessment at ~26 months of age. She was diagnosed with CAS by an evaluating SLP and was found to be eligible for speech-language services, which she began receiving shortly thereafter. However, Mrs. Q noted that TQ was making very few gains in therapy and her treating SLP was uncertain regarding why her progress in therapy was so limited. Mrs. Q was also rather uncertain that TQ’s diagnosis of CAS was indeed a correct one, which was another reason why she sought a second opinion. TQ’s oral peripheral examination yielded no difficulties with oral movements during non-speaking as well as speaking tasks. She was able to blow bubbles, stick out tongue, smile, etc as well as spontaneously vocalize without any difficulties. Her voice quality, pitch, loudness, and resonance during vocalizations and approximated utterances were judged to be appropriate for age and gender. Her prosody and fluency could not be determined due to lack of spontaneously produced continuous verbal output.

TQ’s oral peripheral examination yielded no difficulties with oral movements during non-speaking as well as speaking tasks. She was able to blow bubbles, stick out tongue, smile, etc as well as spontaneously vocalize without any difficulties. Her voice quality, pitch, loudness, and resonance during vocalizations and approximated utterances were judged to be appropriate for age and gender. Her prosody and fluency could not be determined due to lack of spontaneously produced continuous verbal output. I felt that the diagnosis of CAS was not applicable because TQ lacked a verbal lexicon and no specific phonological intervention techniques had been trialed with her during the course of her brief therapy (~4 months) to elicit word productions (Davis & Velleman, 2000; Strand, 2003). While her EI speech therapist documented that therapy has primarily focused on ‘oral motor activities to increase TQ’s awareness of her articulators and to increase imitation of oral motor movements’, I knew that until a variety of phonological/motor-speech specific interventions had been trialed over a period of time (at least ~6 months as per Davis & Velleman, 2000) the diagnosis of CAS could not be reliably made.

I felt that the diagnosis of CAS was not applicable because TQ lacked a verbal lexicon and no specific phonological intervention techniques had been trialed with her during the course of her brief therapy (~4 months) to elicit word productions (Davis & Velleman, 2000; Strand, 2003). While her EI speech therapist documented that therapy has primarily focused on ‘oral motor activities to increase TQ’s awareness of her articulators and to increase imitation of oral motor movements’, I knew that until a variety of phonological/motor-speech specific interventions had been trialed over a period of time (at least ~6 months as per Davis & Velleman, 2000) the diagnosis of CAS could not be reliably made. *For those of you who are interested in the latest EBP treatment for motor speech disorders, current evidence supports the use of the

*For those of you who are interested in the latest EBP treatment for motor speech disorders, current evidence supports the use of the  Now I know that some clinicians will be quick to ask me: “What’s the harm in overdiagnosing CAS if the child’s speech production will still be treated via the application of motor speech production principles?” Well, aside from the fact that it’s obviously unethical and can result in terrifying the parents into obtaining all sorts of

Now I know that some clinicians will be quick to ask me: “What’s the harm in overdiagnosing CAS if the child’s speech production will still be treated via the application of motor speech production principles?” Well, aside from the fact that it’s obviously unethical and can result in terrifying the parents into obtaining all sorts of