Teaching Hierarchy of Problem Solving Skills to Children with Learning Disabilities (Revised)

Today I want to talk treatment. That thing that we need to plan for as we are doing our assessments. But are we starting our treatments the right way? The answer may surprise you. I often see SLPs phrasing questions regarding treatment the following way: “I have a student diagnosed with ____ (insert disorder here). What is everyone using (program/app/materials) during therapy sessions to address ___ diagnosis?”

Today I want to talk treatment. That thing that we need to plan for as we are doing our assessments. But are we starting our treatments the right way? The answer may surprise you. I often see SLPs phrasing questions regarding treatment the following way: “I have a student diagnosed with ____ (insert disorder here). What is everyone using (program/app/materials) during therapy sessions to address ___ diagnosis?”

Of course, the answer is never that simple. Just because a child has a diagnosis of a social communication disorder, word-finding deficits, or a reading disability does not automatically indicate to the treating clinician, which ‘cookie cutter’ materials and programs are best suited for the child in question. Only a profile of strengths and needs based on a comprehensive language and literacy testing can address this in an adequate and targeted manner.

To illustrate, reading intervention is a much debated and controversial topic nowadays. Everywhere you turn there’s a barrage of advice for clinicians and parents regarding which program/approach to use. Barton, Wilson, OG… the well-intentioned advice just keeps on coming. The problem is that without knowing the child’s specific deficit areas, the application of the above approaches is quite frankly … pointless.

There could be endless variations of how deficits manifest in poor readers. Is it aspects of phonological awareness, phonics, morphology, etc. What combination of deficits is preventing the child from becoming a good reader?

There could be endless variations of how deficits manifest in poor readers. Is it aspects of phonological awareness, phonics, morphology, etc. What combination of deficits is preventing the child from becoming a good reader?

Let’s a take a look at an example, below. It’s the CTOPP-2 results of a 7-6-year-old female with a documented history of extensive reading difficulties and a significant family history of reading disabilities in the family.

Results of the Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing-2 (CTOPP-2)

| Subtests | Scaled Scores | Percentile Ranks | Description |

| Elision (EL) | 7 | 16 | Below Average |

| Blending Words (BW) | 13 | 84 | Above Average |

| Phoneme Isolation (PI) | 6 | 9 | Below Average |

| Memory for Digits (MD) | 8 | 25 | Average |

| Nonword Repetition (NR) | 8 | 25 | Average |

| Rapid Digit Naming (RD) | 10 | 50 | Average |

| Rapid Letter Naming (RL) | 11 | 63 | Average |

| Blending Nonwords (BN) | 8 | 25 | Average |

| Segmenting Nonwords (SN) | 8 | 25 | Average |

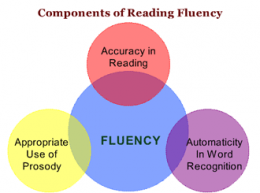

However, the results of her CTOPP-2 testing clearly indicate that phonological awareness, despite two areas of mild weaknesses, is not really a significant problem for this child. So let’s look at the student’s reading fluency results.

Reading Fluency: “LG’s reading fluency during this task was judged to be significantly affected by excessive speed, inappropriate pausing, word misreadings, choppy prosody, as well as inefficient word attack skills. While she was able to limitedly utilize the phonetic spelling of unfamiliar words (e.g., __) provided to her in parenthesis next to the word (which she initially misread as ‘__’), she exhibited limited use of metalinguistic strategies (e.g., pre-scanning sentences to aid text comprehension, self-correcting to ensure that the read words made sense in the context of the sentence, etc.), when reading the provided passage. To illustrate, during the reading of the text, LG was observed to frequently (at least 3 times) lose her place and skip entire lines of text without any attempts at self-correction. At times she was observed to read the same word a number of different ways (e.g., read ‘soup’ as ‘soup’ then as ‘soap’, ‘roots’ as ‘roofs’ then as ‘roots’, etc.) without attempting to self-correct. LG’s oral reading rate was also observed to be impaired for her age/grade levels. Her prosody was significantly adversely affected due to lack of adequate pausing for punctuation marks (e.g., periods, commas, etc.). Instead, she paused during text reading only when he could not decode select words in the text. Though, LG was able to read 70 words per minute, which was judged to be grossly commensurate with grade-level, out of these 70 words she skipped 2 entire lines of text, invented an entire line of text, as well as made 4 decoding errors and 6 inappropriate pauses.”

Reading Fluency: “LG’s reading fluency during this task was judged to be significantly affected by excessive speed, inappropriate pausing, word misreadings, choppy prosody, as well as inefficient word attack skills. While she was able to limitedly utilize the phonetic spelling of unfamiliar words (e.g., __) provided to her in parenthesis next to the word (which she initially misread as ‘__’), she exhibited limited use of metalinguistic strategies (e.g., pre-scanning sentences to aid text comprehension, self-correcting to ensure that the read words made sense in the context of the sentence, etc.), when reading the provided passage. To illustrate, during the reading of the text, LG was observed to frequently (at least 3 times) lose her place and skip entire lines of text without any attempts at self-correction. At times she was observed to read the same word a number of different ways (e.g., read ‘soup’ as ‘soup’ then as ‘soap’, ‘roots’ as ‘roofs’ then as ‘roots’, etc.) without attempting to self-correct. LG’s oral reading rate was also observed to be impaired for her age/grade levels. Her prosody was significantly adversely affected due to lack of adequate pausing for punctuation marks (e.g., periods, commas, etc.). Instead, she paused during text reading only when he could not decode select words in the text. Though, LG was able to read 70 words per minute, which was judged to be grossly commensurate with grade-level, out of these 70 words she skipped 2 entire lines of text, invented an entire line of text, as well as made 4 decoding errors and 6 inappropriate pauses.”

So now we know that despite quite decent phonological awareness abilities, this student presents with quite poor sound-letter correspondence skills and will definitely benefit from explicit phonics instruction addressing the above deficit areas. But that is only the beginning! By looking at the analysis of specific misreadings we next need to determine what other literacy areas need to be addressed. For the sake of brevity, I can specify that further analysis of this child reading abilities revealed that reading comprehension, orthographic knowledge, as well as morphological awareness were definitely areas that also required targeted remediation. The assessment also revealed that the child presented with poor spelling and writing abilities, which also needed to be addressed in the context of therapy.

Now, what if I also told you that this child had already been receiving private, Orton-Gillingham reading instruction for a period of 2 years, 1x per week, at the time the above assessment took place? Would you change your mind about the program in question?

Well, the answer is again not so simple! OG is a fine program, but as you can see from the above example it has definite limitations and is not an exclusive fit for this child, or for any child for that matter. Furthermore, a solidly-trained in literacy clinician DOES NOT need to rely on just one program to address literacy deficits. They simply need solid knowledge of typical and atypical language and literacy development/milestones and know how to create a targeted treatment hierarchy in order to deliver effective intervention services. But for that, they need to first, thoughtfully, construct assessment-based treatment goals by carefully taking into the consideration the child’s strengths and needs.

So let’s stop asking which approach/program we should use and start asking about the child’s profile of strengths and needs in order to create accurate language and literacy goals based on solid evidence and scientifically-guided treatment practices.

Helpful Resources Pertaining to Reading:

In March 2014, ASHA SIG 16 Perspectives on School Based Issues, I’ve written an article on how SLPs can collaborate with other school based professionals to successfully work with children exhibiting challenging behaviors secondary to psychiatric diagnoses and emotional and behavioral disturbances. In this post I would like to summarize the key points of my article as well as offer helpful professional resources on this topic. Continue reading Creating Successful Team Collaboration: Behavior Management in the Schools

In March 2014, ASHA SIG 16 Perspectives on School Based Issues, I’ve written an article on how SLPs can collaborate with other school based professionals to successfully work with children exhibiting challenging behaviors secondary to psychiatric diagnoses and emotional and behavioral disturbances. In this post I would like to summarize the key points of my article as well as offer helpful professional resources on this topic. Continue reading Creating Successful Team Collaboration: Behavior Management in the Schools

In the past a number of my SLP colleague bloggers (Communication Station, Twin Sisters SLPs, Practical AAC, etc.) wrote posts regarding the use of thematic texts for language intervention purposes. They discussed implementation of fictional texts such as the use of children’s books and fairy tales to target linguistic goals such as vocabulary knowledge in use, sentence formulation, answering WH questions, as well as story recall and production.

In the past a number of my SLP colleague bloggers (Communication Station, Twin Sisters SLPs, Practical AAC, etc.) wrote posts regarding the use of thematic texts for language intervention purposes. They discussed implementation of fictional texts such as the use of children’s books and fairy tales to target linguistic goals such as vocabulary knowledge in use, sentence formulation, answering WH questions, as well as story recall and production.

Today I would like to supplement those posts with information regarding the implementation of intervention based on thematic nonfiction texts to further improve language abilities of children with language difficulties.

First, here’s why the use of nonfiction texts in language intervention is important. While narrative texts have high familiarity for children due to preexisting, background knowledge, familiar vocabulary, repetitive themes, etc. nonfiction texts are far more difficult to comprehend. It typically contains unknown concepts and vocabulary, which is then used in the text multiple times. Therefore lack of knowledge of these concepts and related vocabulary will result in lack of text comprehension. According to Duke (2013) half of all the primary read-alouds should be informational text. It will allow students to build up knowledge and the necessary academic vocabulary to effectively participate and partake from the curriculum.

So what type of nonfiction materials can be used for language intervention purposes. While there is a rich variety of sources available, I have had great success using Let’s Read and Find Out Stage 1 and 2 Science Series with clients with varying degrees of language impairment.

Here’s are just a few reasons why I like to use this series.

For example, the above books on weather and seasons contain information on:

1. Front Formations

2. Water Cycle

3. High & Low Pressure Systems

Let’s look at the vocabulary words from Flash, Crash, Rumble, and Roll (see detailed lesson plan HERE). (Source: ReadWorks):

Word: water vapor

Context: Steam from a hot soup is water vapor.

Word: expands

Context: The hot air expands and pops the balloon.

Word: atmosphere

Context: The atmosphere is the air that covers the Earth.

Word: forecast

Context: The forecast had a lot to tell us about the storm.

Word: condense

Context: steam in the air condenses to form water drops.

These books are not just great for increasing academic vocabulary knowledge and use. They are great for teaching sequencing skills (e.g., life cycles), critical thinking skills (e.g., What do animals need to do in the winter to survive?), compare and contrast skills (e.g., what is the difference between hatching and molting?) and much, much, more!

So why is use of nonfiction texts important for strengthening vocabulary knowledge and words in language impaired children?

As I noted in my previous post on effective vocabulary instruction (HERE): “teachers with many struggling children often significantly reduce the quality of their own vocabulary unconsciously to ensure understanding” (Excerpts from Anita Archer’s Interview with Advance for SLPs).

The same goes for SLPs and parents. Many of them are under misperception that if they teach complex subject-related words like “metamorphosis” or “vaporization” to children with significant language impairments or developmental disabilities that these students will not understand them and will not benefit from learning them.

However, that is not the case! These students will still significantly benefit from learning these words, it will simply take them longer periods of practice to retain them!

By simplifying our explanations, minimizing verbiage and emphasizing the visuals, the books can be successfully adapted for use with children with severe language impairments. I have had parents observe my intervention sessions using these books and then successfully use them in the home with their children by reviewing the information and reinforcing newly learned vocabulary knowledge.

Here are just a few examples of prompts I use in treatment with more severely affected language-impaired children:

Here are the questions related to Sequencing of Processes (Life Cycle, Water Cycle, etc.)

As the child advances his/her skills I attempt to engage them in more complex book interactions

“Picture walks” (flipping through the pages) of these books are also surprisingly effective for activation of the student’s background knowledge (what a student already knows about a subject). This is an important prerequisite skill needed for continued acquisition of new knowledge. It is important because “students who lack sufficient background knowledge or are unable to activate it may struggle to access, participate, and progress through the general curriculum” (Stangman, Hall & Meyer, 2004).

These book allow for :

1.Learning vocabulary words in context embedded texts with high interest visuals

2.Teaching specific content related vocabulary words directly to comprehend classroom-specific work

3.Providing multiple and repetitive exposures of vocabulary words in texts

4. Maximizing multisensory intervention when learning vocabulary to maximize gains (visual, auditory, tactile via related projects, etc.)

To summarize, children with significant language impairment often suffer from the Matthew Effect (“rich get richer, poor get poorer”), or interactions with the environment exaggerate individual differences over time

Children with good vocabulary knowledge learn more words and gain further knowledge by building of these words

Children with poor vocabulary knowledge learn less words and widen the gap between self and peers over time due to their inability to effectively meet the ever increasing academic effects of the classroom. The vocabulary problems of students who enter school with poorer limited vocabularies only worsen over time (White, Graves & Slater, 1990). We need to provide these children with all the feasible opportunities to narrow this gap and partake from the curriculum in a more similar fashion as typically developing peers.

Helpful Smart Speech Therapy Resources:

References:

Duke, N. K. (2013). Starting out: Practices to Use in K-3. Educational Leadership, 71, 40-44.

Marzano, R. J., & Marzano, J. (1988). Toward a cognitive theory of commitment and its implications for therapy. Psychotherapy in Private Practice 6(4), 69–81.

Stahl, S. A. & Fairbanks, M. M. “The Effects of Vocabulary Instruction: A Model-based Metaanalysis.” Review of Educational Research 56 (1986): 72-110.

Strangman, N., Hall, T., & Meyer, A. (2004). Background knowledge with UDL. Wakefield, MA: National Center on Accessing the General Curriculum.

White, T. G., Graves, M. F., & Slater W. H. (1990). Growth of reading vocabulary in diverse elementary schools: Decoding and word meaning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 281–290.

In my social pragmatic language groups I target a wide variety of social communication goals for children with varying levels and degrees of impairment with a focus on improving their social pragmatic language competence. In the past I have written blog posts on a variety of social pragmatic language therapy topics, including strategies for improving students’ emotional intelligence as well as on how to teach students to develop insight into own strengths and weaknesses. Today I wanted to discuss the importance of teaching students with social communication impairments, age recognition for friendship and safety purposes.

In my social pragmatic language groups I target a wide variety of social communication goals for children with varying levels and degrees of impairment with a focus on improving their social pragmatic language competence. In the past I have written blog posts on a variety of social pragmatic language therapy topics, including strategies for improving students’ emotional intelligence as well as on how to teach students to develop insight into own strengths and weaknesses. Today I wanted to discuss the importance of teaching students with social communication impairments, age recognition for friendship and safety purposes.

Now it is important to note that the focus of my sessions is a bit different from the focus of “teaching protective behaviors”, “circles of intimacy and relationships” or “teaching kids to deal with tricky people“. Rather the goal is to teach the students to recognize who it is okay “to hang out” or be friends with, and who is considered to be too old/too young to be a friend.

Why is it important to teach age recognition?

There are actually quite a few reasons.

Firstly, it is a fairly well-known fact that in the absence of age-level peers with similar weaknesses, students with social communication deficits will seek out either much younger or much older children as playmates/friends as these individuals are far less likely to judge them for their perceived social deficits. While this may be a short-term solution to the “friendship problem” it also comes with its own host of challenges. By maintaining relationships with peers outside of their age group, it is difficult for children with social communication impairments to understand and relate to peers of their age group in school setting. This creates a wider chasm in the classroom and increases the risk of peer isolation and bullying.

Secondly, the difficulty presented by friendships significantly outside of one’s peer group, is the risk of, for lack of better words, ‘getting into trouble’. This may include but is not limited to exploring own sexuality (which is perfectly normal) with a significantly younger child (which can be problematic) or be instigated by an older child/adolescent in doing something inappropriate (e.g, shoplifting, drinking, smoking, exposing self to peers, etc.).

Thirdly, this difficulty (gauging people’s age) further exacerbates the students’ social communication deficits as it prevents them from effectively understanding such pragmatic parameters such as audience (e.g., with whom its appropriate to use certain language in a certain tone and with whom it is not) and topic (with whom it is appropriate to discuss certain subjects and with whom it is not).

![]()

So due to the above reasons I began working on age recognition with the students (6+ years of age) on my caseload diagnosed with social communication and language impairments. I mention language impairments because it is very important to understand that more and more research is coming out connecting language impairments with social communication deficits. Therefore it’s not just students on the autism spectrum or students with social pragmatic deficits (an official DSM-5 diagnosis) who have difficulties in the area of social communication. Students with language impairments could also benefit from services focused on improving their social communication skills.

I begin my therapy sessions on age recognition by presenting the students with photos of people of different ages and asking them to attempt to explain how old do they think the people in the pictures are and what visual clues and/or prior knowledge assisted them in the formulation of their responses. I typically select the pictures from some of the social pragmatic therapy materials packets that I had created over the years (e.g., Gauging Moods, Are You Being Social?, Multiple Interpretations, etc.).

I make sure to carefully choose my pictures based on the student’s age and experience to ensure that the student has at least some degree of success making guesses. So for a six-year-old I would select pictures of either toddlers or children his/her age to begin teaching them recognition of concepts: “same” and “younger” (e.g., Social Pragmatic Photo Bundle for Early Elementary Aged Children).

For older children, I vary the photos of different aged individuals significantly. I also introduce relevant vocabulary words as related to a particular age demographic, such as:

I explain to the students that people of different ages look differently and teach them how to identify relevant visual clues to assist them with making educated guesses about people’s ages. I also use photos of my own family or ask the students to bring in their own family photos to use for age determination of people in the presented pictures. When students learn the ages of their own family members, they have an easier time determining the age ranges of strangers.

My next step is to explain to students the importance of understanding people’s ages. I present to the students a picture of an individual significantly younger or older than them and ask them whether it’s appropriate to be that person’s friend. Here students with better developed insight will state that it is not appropriate to be that person’s friend because they have nothing in common with them and do not share their interests. In contrast, students with limited insight will state that it’s perfectly okay to be that person’s friend.

This is the perfect teachable moment for explaining the difference between “friend” and “friendly”. Here I again reiterate that people of different ages have significantly different interests as well as have significant differences in what they are allowed to do (e.g., a 16-year-old is allowed to have a driver’s permit in many US states as well as has a later curfew while an 11-year-old clearly doesn’t). I also explain that it’s perfectly okay to be friendly and polite with older or younger people in social situations (e.g., say hello all, talk, answer questions, etc.) but that does not constitute true friendship.

I also ask students to compile a list of qualities of what they look for in a “friend” as well as have them engage in some perspective taking (e.g, have them imagine that they showed up at a toddler’s house and asked to play with him/her, or that a teenager came into their house, and what their parents reaction would be?).

Finally, I discuss with students the importance of paying attention to who wants to hang out/be friends with them as well as vice versa (individuals they want to hang out with) in order to better develop their insight into the appropriateness of relationships. I instruct them to think critically when an older individual (e.g, young adult) wants to get particularly close to them. I use examples from an excellent post written by a colleague and good friend, Maria Del Duca of Communication Station Blog re: dealing with tricky people, in order to teach them to recognize signs of individuals crossing the boundary of being friendly, and what to do about it.

So there you have it. These are some of the reasons why I teach age recognition to clients with social communication weaknesses. Do you teach age recognition to your clients? If so, comment under this post, how do you do it and what materials do you use?

Helpful Smart Speech Resources Related to Assessment and Treatment of Social Pragmatic Disorders

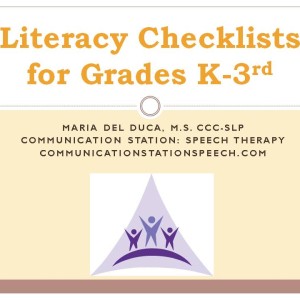

Today I am bringing you yet another giveaway from the fabulous Maria Del Duca of Communication Station Blog entitled: “Literacy Checklists for K-3rd Grade“. She created a terrific set of checklists to address reading comprehension and written expression in children K-3rd grade because according to Maria: “dynamic assessment of functional skills, when done well, can at times yield more accurate and salient information than standardized tests.”

This 10 page packet uses observational as well as teacher and parent reported information to present a holistic view of a child’s literacy skills with a focus on the following areas: Continue reading Birthday Extravaganza Day Twenty Eight: Literacy Checklists for Grades K-3

Last year an esteemed colleague, Dr. Roseberry-McKibbin posed this question in our Bilingual SLPs Facebook Group: “Is anyone working on morphological awareness in therapy with ELLs (English Language Learners) with language disorders?”

Last year an esteemed colleague, Dr. Roseberry-McKibbin posed this question in our Bilingual SLPs Facebook Group: “Is anyone working on morphological awareness in therapy with ELLs (English Language Learners) with language disorders?”

Her question got me thinking: “How much time do I spend on treating morphological awareness in therapy with monolingual and bilingual language disordered clients?” The answer did not make me happy!

So what is morphological awareness and why is it important to address when treating monolingual and bilingual language impaired students?

Morphemes are the smallest units of language that carry meaning. They can be free (stand alone words such as ‘fair’, ‘toy’, or ‘pretty’) or bound (containing prefixes and suffixes that change word meanings – ‘unfair’ or ‘prettier’).

Morphological awareness refers to a ‘‘conscious awareness of the morphemic structure of words and the ability to reflect on and manipulate that structure’’ (Carlisle, 1995, p. 194). Also referred to as “the study of word structure” (Carlisle, 2004), it is an ability to recognize, understand, and use affixes or word parts (prefixes, suffixes, etc) that “carry significance” when speaking as well as during reading tasks. It is a hugely important skill for building vocabulary, reading fluency and comprehension as well as spelling (Apel & Lawrence, 2011; Carlisle, 2000; Binder & Borecki, 2007; Green, 2009).

So why is teaching morphological awareness important? Let’s take a look at some research.

Goodwin and Ahn (2010) found morphological awareness instruction to be particularly effective for children with speech, language, and/or literacy deficits. After reviewing 22 studies Bowers et al. (2010) found the most lasting effect of morphological instruction was on readers in early elementary school who struggled with literacy.

Morphological awareness instruction mediates and facilitates vocabulary acquisition leading to improved reading comprehension abilities (Bowers & Kirby, 2010; Carlisle, 2003, 2010; Guo, Roehrig, & Williams, 2011; Tong, Deacon, Kirby, Cain, & Parilla, 2011).

Unfortunately as important morphological instruction is for vocabulary building, reading fluency, reading comprehension, and spelling, it is often overlooked during the school years until it’s way too late. For example, traditionally morphological instruction only beings in late middle school or high school but research actually found that in order to be effective one should actually begin teaching it as early as first grade (Apel & Lawrence, 2011).

So now that we know that we need to target morphological instruction very early in children with language deficits, let’s talk a little bit regarding how morphological awareness can be assessed in language impaired learners.

When it comes to standardized testing, both the Test of Language Development: Intermediate – Fourth Edition (TOLD-I:4) and the Test of Adolescent and Adult Language–Fourth Edition (TOAL-4) have subtests which assess morphology as well as word derivations. However if you do not own either of these tests you can easily create non-standardized tasks to assess morphological awareness.

Apel, Diehm, & Apel (2013) recommend multiple measures which include: phonological awareness tasks, word level reading tasks, as well as reading comprehension tasks.

Below are direct examples of tasks from their study:

One can test morphological awareness via production or decomposition tasks. In a production task a student is asked to supply a missing word, given the root morpheme (e.g., ‘‘Sing. He is a great _____.’’ Correct response: singer). A decomposition task asks the student to identify the correct root of a given derivation or inflection. (e.g., ‘‘Walker. How slow can she _____?’’ Correct response: walk).

Another way to test morphological awareness is through completing analogy tasks since it involves both decomposition and production components (provide a missing word based on the presented pattern—crawl: crawled:: fly: ______ (flew).

Still another way to test morphological awareness with older students is through deconstruction tasks: Tell me what ____ word means? How do you know? (The student must explain the meaning of individual morphemes).

Finding the affix: Does the word ______ have smaller parts?

So what are the components of effective morphological instruction you might ask?

Below is an example of a ‘Morphological Awareness Intervention With Kindergarteners and First and Second Grade Students From Low SES Homes’ performed by Apel & Diehm, 2013:

Here are more ways in which this can be accomplished with older children:

Now that you know about the importance of morphological awareness, will you be incorporating it into your speech language sessions? I’d love to know!

Until then, Happy Speeching!

References:

Those of us who have administered PLS-5 ever since its release in 2011, know that the test is fraught with significant psychometric problems. Previous reviews of its poor sensitivity, specificity, validity, and reliability, have been extensively discussed HERE and HERE as well as in numerous SLP groups on Facebook.

Those of us who have administered PLS-5 ever since its release in 2011, know that the test is fraught with significant psychometric problems. Previous reviews of its poor sensitivity, specificity, validity, and reliability, have been extensively discussed HERE and HERE as well as in numerous SLP groups on Facebook.

One of the most significant issues with this test is that its normative sample included a “clinical sample of 169 children aged 2-7;11 diagnosed with a receptive or expressive language disorder”.

The problem with such inclusion is that According to Pena, Spalding, & Plante, (2006) when the purpose of a test is to identify children with language impairment, the inclusion of children with language impairment in the normative sample can reduce the accuracy of identification.

Indeed, upon its implementation, many clinicians began to note that this test significantly under-identified children with language impairments and overinflated their scores. As such, based on its presentation, due to strict district guidelines and qualification criteria, many children who would have qualified for services with the administration of the PLS-4, no longer qualified for services when administered the PLS-5.

For years, SLPs wrote to Pearson airing out their grievances regarding this test with responses ranging from irate to downright humorous as one can see from the below response form (helpfully provided by an anonymous responder).

And now it appears that Pearson is willing to listen. A few days ago, many of us who have purchased this test received the following email:  It contains the link to a survey powered by Survey Monkey, asking clinicians their feedback regarding PLS-5 administration and how it can be improved. So if you are one of those clinicians, please go ahead and provide your honest feedback regarding this test, after all, our littlest clients deserve so much better than to be under-identified by this assessment and denied services as a result of its administration.

It contains the link to a survey powered by Survey Monkey, asking clinicians their feedback regarding PLS-5 administration and how it can be improved. So if you are one of those clinicians, please go ahead and provide your honest feedback regarding this test, after all, our littlest clients deserve so much better than to be under-identified by this assessment and denied services as a result of its administration.

References: