Recognizing Speech-Language Delay in School-Age Children

In mid-2014, I purchased the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals®, Fifth Edition Metalinguistics (CELF®-5 Metalinguistics), which is a revision of the Test of Language Competence–Expanded.

In mid-2014, I purchased the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals®, Fifth Edition Metalinguistics (CELF®-5 Metalinguistics), which is a revision of the Test of Language Competence–Expanded.

Basic overview

Release date: 2014

Age Range: 9-21

Author: Elizabeth Wiig and Wayne Secord

Publisher: Pearson

Description: According to the manual CELF–5M was created to “identify students 9-21 years old who have not acquired the expected levels of communicative competence and metalinguistic ability for their age” (pg. 1). In other words the test targets higher level language skills beyond the basic vocabulary and grammar knowledge and use. The authors recommend using this test with students with “subtle language disorders” or “those on the autism spectrum”.

The test contains 5 subtests:

The Metalinguistics Profile subtest of the CELF-5:M is a questionnaire (filled out by caregiver or teacher) which targets three areas: Words, Concepts, and Multiple Meanings; Inferences and Predictions; as well as Conversational Knowledge and Use. Its aim is to obtain information about a student’s metalinguistic skills in everyday educational and social contexts to complement the evidence of metalinguistic strengths and weaknesses identified by the other subtests that comprise the CELF-5:M test battery.

Questions address such topics as the child’s comprehension of idioms and abstract language, their predicting and inferencing abilities, their ability to deal with unpleasant situations, participate in group discussions, as well as understand jokes and sarcasm, just to name a few. A maximum of four points can be obtained on each of it 30 questions. The following is the rating criteria: a score of one is obtained when a child ‘never’ does something in a particular category (e.g., doesn’t get the punchline of jokes). A score of two is given when a child is capable of understanding or using something ‘some of the time’. A score of three is given when a child is able to understand or perform something ‘often’. Finally, a score of four is given when a child is capable of comprehending something ‘always’ or ‘almost always’.

A word of caution, when giving this profile to either teachers or parents to fill out, the SLP must ensure that no overinflation or underestimation of scores takes place. Frequently, some parents may not have a clear understanding of the extent of their child’s level of deficits. Similarly, some teachers, especially those who may not know the child very well, or those who have worked with a child for a very short period of time, may overinflate the scores when filling out the questionnaire. However, the opposite may also occur. A small group of parents may underestimate their children’s abilities, and provide poor scores as a result also not providing an objective picture of the child’s level of deficits. In such situations, the best option may be for the SLP to fill out the questionnaire together with the parent or teacher in order to provide explanations of questions in a different categories.

The Making Inferences subtest of the CELF-5:M evaluates the student’s ability to identify and formulate logical inferences on the basis of existing causal relationships presented in short narrative texts. The student is visually and auditorily presented with a particular situation by the examiner. S/he is then asked to identify the best two out of four written answers for the ending and come up with her own additional reason other than the ones listed in the stimulus book.

On the multiple choice portion of the subtest errors can result due to provision of contradictory, unrelated and irrelevant responses. On the open ended questions portion of the subtest errors can result due to vague, confusing, incomplete, unlikely or illogical responses as well as due to contradictory and off topic answers.

I must say that this is my least favorite subtest. Here’s why. In real life students are not provided with multiple choices when asked to make predictions or inferences. That is why I do not believe that performance on this subtest is a true representation of the child’s ability in this area.

The Conversational Skills subtest of the CELF-5:M evaluates the student’s ability to initiate a conversation or respond in a way that is relevant and pragmatically appropriate to the context and audience while incorporating given words in semantically and syntactically correct sentences. S/he are presented with a picture scene that creates a conversational context and two or three words which are also printed above the pictured scene. S/he are then asked to formulate a conversationally and pragmatically appropriate sentence for the given context using all of the target words in the form (tense, number, etc.) provided.

Errors on this subtest can result due to pragmatic, semantic or syntactic errors. With respect to pragmatics errors can result due to illogical, nonsensical, vague or incomplete sentences as well as due to sentence formulation which does not take into account presented scenes. With respect to semantics errors can result due to missing or misused target words as well as due to vague, incorrect or misused verbiage. With respect to syntax errors can result due to use of sentence fragments, morphological misuse of target words (changing word forms) as well as syntact deviations on non-target words.

Errors on this subtest can result due to pragmatic, semantic or syntactic errors. With respect to pragmatics errors can result due to illogical, nonsensical, vague or incomplete sentences as well as due to sentence formulation which does not take into account presented scenes. With respect to semantics errors can result due to missing or misused target words as well as due to vague, incorrect or misused verbiage. With respect to syntax errors can result due to use of sentence fragments, morphological misuse of target words (changing word forms) as well as syntact deviations on non-target words.

The Multiple Meanings subtest of the CELF-5:M evaluates the student’s ability to recognize and interpret different meanings of selected lexical (word level) and structural (sentence level) ambiguities. S/he are presented a sentence (orally and in text) that contained an ambiguity at either the word or sentence level. S/he are then asked to describe two meanings for each presented sentence.

Errors can result due to difficulty interpreting lexical and structural ambiguities as well as due to an inability to provide more than one interpretation to presented multiple meaning words.

The Figurative Language subtest of the CELF-5:M evaluates the student’s ability to interpret figurative expressions (idioms) within a given context and match each expression with another figurative expression of similar meaning given verbal and written support.

Errors on this subtest can result due to difficulty explaining the meanings of idiomatic expressions, as well as due to difficulty selecting the appropriate meaning from visually provided multiple choice answers containing related idiomatic expressions.

Based on testing the following long-term goal can be generated:

LTG: Student will improve his/her metalinguistic abilities (thinking about language) for academic and social purposes

It can also yield the following short-term goals

A word of caution regarding testing eligibility:

What I am concerned about:

What I am concerned about:

Consequently the CELF-5: M administration is not for everyone. As mentioned before I would only administer portions of this test to higher functioning (but not too high functioning) students undergoing language assessment for the first time or to higher functioning students receiving a re-evaluation, who have previously passed the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-5 with ease. This test would not be appropriate for Severely Challenged and Challenged Social Communicators (see Winner, 2015)

I would also not administer this test to the following populations:

I would not administer the CELF-5:M to the latter two groups of students due to significantly increased potential for linguistic and cultural bias stemming from lack of previous knowledge and exposure to popular culture as well as idiomatic expressions.

I would also not administer this test to Nuance Challenged Social Communicators (Winner, 2015). Specifically to Socially Anxious and Weak Interactive Social Communicators (Winner, 2015). These are the students with average or above average verbal language abilities most of whom did not have language delays when they were young. They have a ‘well-developed social radar’ and they’re highly aware of other people feelings and thoughts. However they have difficulties navigating subtle social cues of others. As a result this particular group of students tends to score quite on metalinguistic and social pragmatic testing of reduced complexity yet still present with pervasive social pragmatic language deficits.

Consequently, Clinical Assessment of Pragmatics (CAPs) administration would better suit their needs.

What I do like about this test:

This test allows me to identify more subtle language-based difficulties in verbal children with average to high average intelligence (or Emerging Social Communicators as per Winner, 2015) who present with metalinguistic and social pragmatic language weaknesses in the following areas:

Overall, this is an nice test to have in your assessment toolkit. Consequently,if SLPs exercise caution in test candidate selection they can obtain very useful information for metalinguistic and social pragmatic language treatment goal purposes.

NEW: Need a CELF-5M Template Report? Find it HERE

3-1-19 Update: Since this review was written in October 2014, I have reviewed other tests, including the Clinical Assessment of Pragmatics (CAPs), which can be substituted and effectively used to delve into metalinguistic abilities of students with social communication difficulties. As such, while I still use the Multiple Meanings and the Figurative Language subtests of the CELF-5M rather frequently due to its suitability for a select number of students that I assess, given its described limitations, I would approach its purchase with caution, if it were the only test to be owned by the therapist for the purpose of assessment (it’s perfectly suitable as part of a battery but not as a standalone and only option).

Helpful Resources Related to Social Pragmatic Language Overview, Assessment and Remediation:

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this post are the personal opinion of the author. The author is not affiliated with Pearson in any way and was not provided by them with any complimentary products or compensation for the review of this product.

I have been making a lot of materials lately in order to disseminate information on a variety of helpful topics including insurance coverage for speech language services, improving feeding abilities in picky eaters, the importance of oro-facial observations during speech- language assessments and so on. I’ve also created an “introduction” series, which offers handouts on popular topics of interest, most recently on the topic of Auditory Processing Disorders (APD), which can be currently found in my online store HERE. Continue reading Introduction to Social Pragmatic Language Disorders

I have been making a lot of materials lately in order to disseminate information on a variety of helpful topics including insurance coverage for speech language services, improving feeding abilities in picky eaters, the importance of oro-facial observations during speech- language assessments and so on. I’ve also created an “introduction” series, which offers handouts on popular topics of interest, most recently on the topic of Auditory Processing Disorders (APD), which can be currently found in my online store HERE. Continue reading Introduction to Social Pragmatic Language Disorders

In the past several years there has been a sharp decline in international adoptions. Whereas in 2004, Americans adopted a record high of 22,989 children from overseas, in 2015, only 5,647 children (a record low in 30 years) were adopted from abroad by American citizens.

In the past several years there has been a sharp decline in international adoptions. Whereas in 2004, Americans adopted a record high of 22,989 children from overseas, in 2015, only 5,647 children (a record low in 30 years) were adopted from abroad by American citizens.

Primary Data Source: Data Source: U.S. State Department Intercountry Adoption Statistics

Secondary Data Source: Why Did International Adoption Suddenly End?

Despite a sharp decline in adoptions many SLPs still frequently continue to receive internationally adopted (IA) children for assessment as well as treatment – immediately post adoption as well as a number of years post-institutionalization.

In the age of social media, it may be very easy to pose questions and receive instantaneous responses on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter with respect to assessment and treatment recommendations. However, it is very important to understand that many SLPs, who lack direct clinical experience in international adoptions may chime in with inappropriate recommendations with respect to the assessment or treatment of these children.

Consequently, it is important to identify reputable sources of information when it comes to speech-language assessment of internationally adopted children.

There are a number of researchers in both US and abroad who specialize in speech-language abilities of Internationally Adopted children. This list includes (but is by far not limited to) the following authors:

The works of these researchers can be readily accessed in the ASHA Journals or via ResearchGate.

Meanwhile, here are some basic facts regarding internationally adopted children that all SLPs and parents need to know.

Demographics:

The question of bilingualism:

Assessment Parameters:

To treat or NOT to Treat?

Helpful Links:

References:

Additional Helpful References:

If someone asked me today how long I’ve been thinking about writing this post I wouldn’t hesitate and say… 3 years. I know this because that’s when I encountered my very first case of “it’s normal”. I had been in private practice for several years, when I was contacted by parents who wanted me to evaluate their 4 year old son due to concerns over his language abilities. When I first opened my office door to let them in I encountered a completely non-verbal child with significant behavioral deficits and limited communicative intent.

I have to confess, as I was conducting an extremely difficult assessment, I was very shocked by the fact that prior to seeing me, the child had not undergone any in-depth assessments with any related professionals despite presenting with pretty significant symptoms, which included: lack of meaningful interaction with toys, stereotypical behaviors (e.g., rapid flicking of his fingers in front of his eyes for extended period of time, perseverative repetitions of unintelligible sounds out of context, etc), temper tantrums, as well as complete absence of words, phrases and sentences for his age. Very tactfully I broached the subject with the parents only to find out that the parents were concerned regarding their child’s development for quite a while, only to be told by over and over again by their pediatrician that “it’s normal”. I hastily bit back my reply, before I could rudely blurt out: “in which universe?” Instead, I finished the assessment, wrote my 8 page report with extensive recommendations and referrals, and began treating the client. Luckily, since that time he had received numerous appropriate interventions from a variety of related professionals and made some nice gains. But to this day I wonder: Would his gains have been greater had his intervention was initiated at an earlier age (e.g., 2 instead of 4)?

Of course, this is by far one of the more extreme examples that I have seen during the course of my relatively short career (less than 10 years of practice) as a speech language pathologist. But I have certainly seen others.

For example, a few years ago through my hospital based job I’ve treated a child with significant unilateral facial weakness, and a host of phonation, articulation, respiration, and resonance symptoms which included: difficulty managing oral secretions, weak voice, hypernasality, dysarthric vocal quality, and a few others. Again, the parent was told by the physician that the child’s facial asymmetry and symptomology was ‘not significant’’ despite the fact that in addition to the above signs, the child also presented with significantly delayed language development, cognitive limitations and severe behavioral manifestations.

Then of course there were a few stutterers with a host of social history red flags who stuttered for a few years well into early school age, each of whose parents were told by their child’s doctor that s/he will grow out of it.

I am not even counting dozens and dozens of phone calls from concerned parents of language delayed toddlers and preschoolers whose pediatricians told them that they’ll “grow out of it” despite the fact that many of these children ended up receiving speech language services for language delays/disorders for several years afterwards.

I’ve also seen professionals without a specialization in International Adoption diagnosing recently adopted older post-institutionalized children with history of severe trauma, profound language delays, alcohol related deficits and symptoms of institutional autism as Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD).

But I don’t want you to think that I am singling out pediatricians in this post. The truth is that if we look closely we will find that this trend of overconfident recommendations is common to a vast majority of both medical and ancillary professionals (e.g., psychologists, occupational therapists, etc) with speech language pathologists not exempt from the above.

I’ve read a psychiatrist’s report, which diagnosed a child with Asperger’s based on a 15 minute conversation with the child, coupled with a brief physical examination (as documented in the child’s clinical record). At my urging (based on the child’s adaptive behavior, linguistic profile and rather superior social pragmatic functioning) the parents sought a second opinion with another psychiatrist, which revealed that the child wasn’t even on the spectrum but had a anxiety disorder, some of which symptoms mimicked Asperger’s (e.g., perseveration on topics of interest).

I’ve read numerous neurological and neuropsychological reports which diagnosed children with ADD based on the symptoms of inattention and impulsivity in select settings (e.g., school only) without a differential diagnosis to rule out language deficits, auditory processing deficits, medical conditions, or acquired syndromes such as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders.

I’ve reviewed occupational therapy evaluations which reported on the language abilities of children vs. fine and gross motor function and sensory integration skills.

One parent even told me that when she asked a speech language therapist (who was treating her child for articulation difficulties) regarding her 10 year old son’s “ginormous” (parent’s words not mine) overbite she was told “he’ll grow into it”. I was told that the pediatric orthodontist did not appreciate that opinion and vigorously voiced his own as he was fitting the child for braces.

So when exactly did some of us decide that a differential diagnosis doesn’t matter? I’d be very curious to know what prompts professionals, who upon seeing some ‘garden variety’ symptoms, which could have a multitude of causes (e.g., inattention, echolalia, lack of speech, etc) decide that there could be only one definitive diagnosis or who merely shrug the displayed signs and accompanying parental concerns aside, expecting both to disappear on their own volition, given the passage of time.

Is it carelessness?

Is it overconfidence in own abilities?

Is it fear of losing face in front of the parent if you don’t have a ready answer?

Is it misguided belief that the child is displaying “textbook” behavior?

Is it “jadedness” or I’ve seen it all, so I know what it is, attitude?

I can venture hundreds more guesses, but it would be merely pointless speculation. Rather I prefer to focus on the intent of this post which is to outline why a differential diagnosis is so important!

1. Differential diagnosis saves lives!

Yes, I know I am only a speech pathologist and it’s true that I have yet to hear from anyone “I need a speech pathologist stat!” After all I don’t specialize in pediatric dysphagia and treat preemies in NICU.

But imagine the following scenario. A young preschool child shows up to your office with a hoarse vocal quality and a history of behavior tantrums. No problem you think, textbook vocal nodules, I got this, case closed! But what if the child was displaying additional symptoms such as stridor, coughing and difficulty breathing when sleeping? What if a few days after you’ve initiated voice therapy or told the parent that the child is too young for it, the child was rushed into the hospital because his airway was obstructed due to a laryngeal papilloma, which almost caused the child to asphyxiate. Still feel confident in your first diagnosis? Yet some speech language therapists routinely accept children into voice therapy without first referring them for an ENT consult that involves endoscopic imaging. Some of you may scoff and tell me, common, when does thing ever happen? Wouldn’t a doctor have picked up on something like that well before a child seen an SLP? Guess what … not necessarily!

Although it may be hard to believe but an EI or school-based SLP may be the first diagnostic professional many children from at-risk backgrounds come in contact with. Obstacles to receiving appropriate early medical care and ancillary services like early intervention may include limited financial means, lack of education or information, and cultural and linguistic barriers. Bilingual, multicultural, domestically adopted and foster care children from low-income households are particularly at risk since their deficits may not be detected until they begin receiving services in EI or preschool. After all, specialized medical care and related services must be sought out and paid for, which may be very hard to do for families from low SES households if they don’t have medical insurance or are having difficulty applying for Medicaid or state health insurance.

Similarly internationally adopted children are also at significant risk of despite the fact that most are adopted by middle class, financially solvent and highly educated parents. With this particular group the barriers to early identification are pre-adoption environmental risk factors (length of institutionalization and quality of medical care in that setting), combined with limited access to information (paucity of prenatal, medical and developmental history details in the adoption records).

2. Sometimes diagnosis DOES matter!

I know, I know, a number of you will try to convince me that we need to treat the symptoms and NOT the label! But humor me for a second! Let’s say you are a medical/ancillary professional (depending whom the child get’s to see first and for what reason) who gets to assess a new preschool patient/client, let’s call him Johnny. So little 4 year old Johnny walk into your office with the following symptoms:

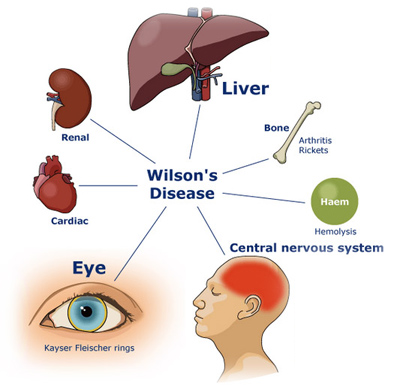

Everything you observe points to the diagnosis of Autism, after all you are the professional, and you’ve seen hundreds of such cases. It’s textbook, right? WRONG! I’ve just described to you some of the symptoms of Wilson’s disease. It’s a genetic disorder in which large amounts of copper build up in the liver and brain. This disorder has degrees of severity ranging from mild/progressive to acute/severe. It can cause brain and nervous system damage, hence the psychiatric and neuromuscular symptoms. The bad news is that this condition can be fatal if misdiagnosed/undiagnosed! The good news is that it is also VERY treatable and can be easily managed with medication, dietary changes, and of course relevant therapies (e.g, PT, OT, ST, etc)!

3. Correct Diagnosis can lead to Appropriate Treatment!

So we all know that ADHD diagnosis is currently being doled out like candy to practically every child with the symptoms of Inattention, Hyperactivity and Impulsivity. But can you actually GUESS how many children are misdiagnosed with it?

Elder (2010), found that nearly 1 million children in US are potentially misdiagnosed with ADHD simply because they are the youngest and most immature in their kindergarten class. Here’s what he has to say on the subject: “A child’s birth date relative to the eligibility cutoff … strongly influences teachers’ assessments of whether the child exhibits ADHD symptoms but is only weakly associated with similarly measured parental assessments, suggesting that many diagnoses may be driven by teachers’ perceptions of poor behavior among the youngest children in a classroom. These perceptions have long-lasting consequences: the youngest children in fifth and eighth grades are nearly twice as likely as their older classmates to regularly use stimulants prescribed to treat ADHD.” (Elder, 2010, 641)

Here are a few examples of ADHD misdiagnosis straight from my caseload.

Case A: 9 year old girl, Internationally Adopted at the age of 16 months diagnosed with ADHD based on the following symptoms:

Prior to medicating the child, the parents sought a language evaluation at the advice of a private social worker. My assessment revealed a language processing disorder and a recommendation for a comprehensive APD assessment with an audiologist. Comprehensive audiological assessment revealed the diagnosis of APD with recommendations for language intervention. After language therapy with a focus on improving the child’s auditory processing skills was initiated, her symptoms improved dramatically. The recommendations for medication were scrapped.

Case B: 12 year old boy attending outpatient school in a psychiatric hospital diagnosed with ADHD and medicated unsuccessfully for it for several years based on the following symptoms:

Detailed case history interview performed prior to initiation of a comprehensive language assessment revealed a history of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) at 18 months of age. Apparently the child was dropped on concrete floor head first by his biological father. However, no medical follow up took place at the time due to lack of household stability. The child was in and out of shelter with mother due to domestic abuse in the home perpetrated by biological father.

The child’s mother reported that he developed speech and language early without difficulties but experienced a significant skills regression around 1.5-2 years of age (hint, hint). Comprehensive language assessment revealed numerous language difficulties, many of which were in the areas of memory, comprehension as well as social pragmatic language. Following the language assessment, relevant medical referrals at the age of 12 substantiated the diagnosis of TBI (better late than never). So no wonder the medication had no effect!

So what can parents do to ensure that their child is being diagnosed appropriately and receives the best possible services from various health professionals?

For starters, make sure to carefully describe all the symptoms that your child presents with (write them down to keep track of them if necessary). It is important to understand that many conditions are dynamic in nature and may change symptoms over time. For example, children with alcohol related disorders may display feeding deficits as infants, delayed developmental milestones as toddlers, good conversational abilities but poor social behavior and abstract thinking skills as school aged children and low academic achievement as adolescents.

Ensure that the professional spends adequate period of time with the child prior to generating a report or rendering a diagnosis. We’ve all been in situations when reports/diagnoses were generated based on a 15 minute cursory visit, which did not involve any follow up testing or when the report was generated based on parental interview vs. actual face to face contact and interaction with the child. THIS IS NOT HOW IT’S SUPPOSED TO WORK! THIS IS HOW MISDIAGNOSES HAPPEN!

Don’t be afraid to ask follow up questions or request rationale for the professionals’ decisions. If you don’t understand something or are skeptical of the results, don’t be afraid to question the findings in a professional way. If the information provided to you seems inadequate or poorly justified consider getting a second opinion with another professional.

Make sure that your child is being treated as a unique individual and not as a textbook subject. Don’t you just hate it when you are trying to describe something to a professional and they look like they are listening but in reality they are not really ‘hearing’ you because they already “know what you have”. Or they are looking at your child but they are not really seeing him/her, because he/she is just another ‘textbook case’ in a long cue of clients. THIS IS NOT THE TREATMENT YOU ARE SUPPOSED TO GET FROM PROFESSIONALS! If this is how your child being treated then maybe it’s time to switch providers!

And another thing there are NO textbook clients! All clients are unique! I currently have about 10 post institutionalized Internationally Adopted children on my caseload with similar deficits but completely different symptom presentation, degrees of severely, as well as overall functioning. Even though some are around the same age, they are so dramatically different from one another that I need to use completely different approaches when I am planning their respective interventions.

Here’s how we as health professionals can better serve our clients/patients needs

It’s all in the details! Carefully collect the client’s background history without leaving anything out. No piece of information is too small/inconsequential! You never know what might be relevant.

Get down to the nitty gritty by asking specific questions. If you ask general questions you’ll get general responses. For example, numerous health care professionals in various fields (doctors, psychiatrists, psychologists, SLPs, etc) routinely ask biological, adoptive and foster parents and adoptive caregivers whether substance abuse of drugs/alcohol took place before and during pregnancy (that they know of with respect to the latter two). A number will respond that yes it took place during pregnancy but stopped as soon as the mother found out she was pregnant. Many professionals will leave it at that and move on to the next line of questioning. However, the follow up question to the above response should always be: “How many months along was the biological mother when she found out she was pregnant?” You’d be surprised at the responses you’ll get, which may significantly clarify the “mystery” of the child’s current symptomology.

Pretend that each new case is your very first case! Remember how you were fresh out of grad school/residency? How much enthusiasm, time, and effort you’ve put in leaving no stone unturned to diagnose your clients? That’s the passion and dedication the parents are looking for.

It’s always fun to play a detective! How cool was “House” when it first came out? House and his team left no stone unturned in trying to correctly diagnose their patients. At times they even went to their houses or places of work in order to find any shred of information that would lead them on the right path. Admittedly you don’t have to go quite that far, but a consultation with a related professional might do the trick if a client is exhibiting certain symptoms outside your experience.

Turn your weakness into strength! No one likes to admit that they don’t have the answer. Many of us worry that our clients (those who work with adults) or their parents (those who work with children) may lose confidence in us and go elsewhere for services. But everything depends on how you frame it! If you simply explain to the parent the rationale for the referral and why you want them to see another specialist prior to formulating the final diagnosis, they will only THANK YOU! It will show them that rather than making a casual decision, you want to make the best decision in their child’s case and they will only appreciate your candor as to them it shows your commitment to the care of their child.

It doesn’t matter how well educated and well trained many medical and related professionals are, the fact remains – no one knows everything! That is why each of us has our own unique scope of practice! That is why we should operate within our scope of practice and referral clients for additional assessments when needed. Differential diagnosis should not be an exception; it should be a rule for any patient who does not show ‘unique’ symptoms indicative of very specific disorders/conditions! It should be performed with far greater frequency than it is done right now by medical and related health professionals!

After all: “When you have excluded all possibilities, then what remains -however improbable – must be the truth”. ~Sherlock Holmes

References:

I wanted to start the new year right by giving away a few copies of a new checklist I recently created entitled: “Comprehensive Literacy Checklist For School-Aged Children“.

I wanted to start the new year right by giving away a few copies of a new checklist I recently created entitled: “Comprehensive Literacy Checklist For School-Aged Children“.

It was created to assist Speech Language Pathologists (SLPs) in the decision-making process of how to identify deficit areas and select assessment instruments to prioritize a literacy assessment for school aged children.

The goal is to eliminate administration of unnecessary or irrelevant tests and focus on the administration of instruments directly targeting the specific areas of difficulty that the student presents with.

*For the purpose of this product, the term “literacy checklist” rather than “dyslexia checklist” is used throughout this document to refer to any deficits in the areas of reading, writing, and spelling that the child may present with in order to identify any possible difficulties the child may present with, in the areas of literacy as well as language.

This checklist can be used for multiple purposes.

1. To identify areas of deficits the child presents with for targeted assessment purposes

2. To highlight areas of strengths (rather than deficits only) the child presents with pre or post intervention

3. To highlight residual deficits for intervention purpose in children already receiving therapy services without further reassessment

Checklist Contents:

Checklist Areas:

You can find this product in my online store HERE.

Would you like to check it out in action? I’ll be giving away two copies of the checklist in a Rafflecopter Giveaway to two winners. So enter today to win your own copy!

Many of my students with Developmental Language Disorders (DLD) lack insight and have poorly developed metalinguistic (the ability to think about and discuss language) and metacognitive (think about and reflect upon own thinking) skills. This, of course, creates a significant challenge for them in both social and academic settings. Not only do they have a poorly developed inner dialogue for critical thinking purposes but they also because they present with significant self-monitoring and self-correcting challenges during speaking and reading tasks. Continue reading Have I Got This Right? Developing Self-Questioning to Improve Metacognitive and Metalinguistic Skills

Many of my students with Developmental Language Disorders (DLD) lack insight and have poorly developed metalinguistic (the ability to think about and discuss language) and metacognitive (think about and reflect upon own thinking) skills. This, of course, creates a significant challenge for them in both social and academic settings. Not only do they have a poorly developed inner dialogue for critical thinking purposes but they also because they present with significant self-monitoring and self-correcting challenges during speaking and reading tasks. Continue reading Have I Got This Right? Developing Self-Questioning to Improve Metacognitive and Metalinguistic Skills

In recent years there has been an increase in research on the subject of diagnosis and treatment of Auditory Processing Disorders (APD), formerly known as Central Auditory Processing Disorders or CAPD.

In recent years there has been an increase in research on the subject of diagnosis and treatment of Auditory Processing Disorders (APD), formerly known as Central Auditory Processing Disorders or CAPD.

More and more studies in the fields of audiology and speech-language pathology began confirming the lack of validity of APD as a standalone (or useful) diagnosis. To illustrate, in June 2015, the American Journal of Audiology published an article by David DeBonis entitled: “It Is Time to Rethink Central Auditory Processing Disorder Protocols for School-Aged Children.” In this article, DeBonis pointed out numerous inconsistencies involved in APD testing and concluded that “routine use of APD test protocols cannot be supported” and that [APD] “intervention needs to be contextualized and functional” (DeBonis, 2015, p. 124) Continue reading Treatment of Children with “APD”: What SLPs Need to Know

Today’s guest post on Williams Syndrome comes from Pamela Mandell, M.S. CCC-SLP with a contribution from Priya Deonarain, MA, OTR/L, CKTP.

Today’s guest post on Williams Syndrome comes from Pamela Mandell, M.S. CCC-SLP with a contribution from Priya Deonarain, MA, OTR/L, CKTP.

Overview

Williams syndrome (WS), also known as Williams-Beuren Syndrome, is a rare genetic disorder caused by the deletion of the long arm of chromosome 7 or, more specifically a microdeletion at 7q11.23, which involves the elastin gene. WS occurs in approximately 1 in 10,000 births worldwide. It is characterized by cardiovascular disease, dysmorphic craniofacial features, a characteristic cognitive and personality profile, deficient visuospatial abilities, hyperacusis, growth retardation, developmental delays, feeding difficulties, and learning disabilities. However, many people with WS exhibit strong expressive language skills and an affinity for music. Mild to severe anxieties as well as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are also associated with WS. The degree of severity or involvement of these characteristics is variable and no two individuals with WS are alike. WS affects both males and females equally. Sadler, et al. (2001), determined the severity of both supravalvular aortic stenosis (SVAS) and total cardiovascular disease was significantly higher in males than females. There is no cure for WS. Patients must be continually monitored and treated for symptoms throughout their lives. Continue reading Spotlight on Syndromes: An SLPs and OTs Perspective on Williams Syndrome