The Test of Integrated Language & Literacy Skills (TILLS) is an assessment of oral and written language abilities in students 6–18 years of age. Published in the Fall 2015, it is unique in the way that it is aimed to thoroughly assess skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, phonological awareness, spelling, as well as writing in school age children. As I have been using this test since the time it was published, I wanted to take an opportunity today to share just a few of my impressions of this assessment.

The Test of Integrated Language & Literacy Skills (TILLS) is an assessment of oral and written language abilities in students 6–18 years of age. Published in the Fall 2015, it is unique in the way that it is aimed to thoroughly assess skills such as reading fluency, reading comprehension, phonological awareness, spelling, as well as writing in school age children. As I have been using this test since the time it was published, I wanted to take an opportunity today to share just a few of my impressions of this assessment.

First, a little background on why I chose to purchase this test so shortly after I had purchased the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – 5 (CELF-5). Soon after I started using the CELF-5 I noticed that it tended to considerably overinflate my students’ scores on a variety of its subtests. In fact, I noticed that unless a student had a fairly severe degree of impairment, the majority of his/her scores came out either low/slightly below average (click for more info on why this was happening HERE, HERE, or HERE). Consequently, I was excited to hear regarding TILLS development, almost simultaneously through ASHA as well as SPELL-Links ListServe. I was particularly happy because I knew some of this test’s developers (e.g., Dr. Elena Plante, Dr. Nickola Nelson) have published solid research in the areas of psychometrics and literacy respectively.

According to the TILLS developers it has been standardized for 3 purposes:

- to identify language and literacy disorders

- to document patterns of relative strengths and weaknesses

- to track changes in language and literacy skills over time

The testing subtests can be administered in isolation (with the exception of a few) or in its entirety. The administration of all the 15 subtests may take approximately an hour and a half, while the administration of the core subtests typically takes ~45 mins).

Please note that there are 5 subtests that should not be administered to students 6;0-6;5 years of age because many typically developing students are still mastering the required skills.

- Subtest 5 – Nonword Spelling

- Subtest 7 – Reading Comprehension

- Subtest 10 – Nonword Reading

- Subtest 11 – Reading Fluency

- Subtest 12 – Written Expression

However, if needed, there are several tests of early reading and writing abilities which are available for assessment of children under 6:5 years of age with suspected literacy deficits (e.g., TERA-3: Test of Early Reading Ability–Third Edition; Test of Early Written Language, Third Edition-TEWL-3, etc.).

Let’s move on to take a deeper look at its subtests. Please note that for the purposes of this review all images came directly from and are the property of Brookes Publishing Co (clicking on each of the below images will take you directly to their source).

1. Vocabulary Awareness (VA) (description above) requires students to display considerable linguistic and cognitive flexibility in order to earn an average score. It works great in teasing out students with weak vocabulary knowledge and use, as well as students who are unable to quickly and effectively analyze words for deeper meaning and come up with effective definitions of all possible word associations. Be mindful of the fact that even though the words are presented to the students in written format in the stimulus book, the examiner is still expected to read all the words to the students. Consequently, students with good vocabulary knowledge and strong oral language abilities can still pass this subtest despite the presence of significant reading weaknesses. Recommendation: I suggest informally checking the student’s word reading abilities by asking them to read of all the words, before reading all the word choices to them. This way you can informally document any word misreadings made by the student even in the presence of an average subtest score.

1. Vocabulary Awareness (VA) (description above) requires students to display considerable linguistic and cognitive flexibility in order to earn an average score. It works great in teasing out students with weak vocabulary knowledge and use, as well as students who are unable to quickly and effectively analyze words for deeper meaning and come up with effective definitions of all possible word associations. Be mindful of the fact that even though the words are presented to the students in written format in the stimulus book, the examiner is still expected to read all the words to the students. Consequently, students with good vocabulary knowledge and strong oral language abilities can still pass this subtest despite the presence of significant reading weaknesses. Recommendation: I suggest informally checking the student’s word reading abilities by asking them to read of all the words, before reading all the word choices to them. This way you can informally document any word misreadings made by the student even in the presence of an average subtest score.

2. The Phonemic Awareness (PA) subtest (description above) requires students to isolate and delete initial sounds in words of increasing complexity. While this subtest does not require sound isolation and deletion in various word positions, similar to tests such as the CTOPP-2: Comprehensive Test of Phonological Processing–Second Edition or the The Phonological Awareness Test 2 (PAT 2), it is still a highly useful and reliable measure of phonemic awareness (as one of many precursors to reading fluency success). This is especially because after the initial directions are given, the student is expected to remember to isolate the initial sounds in words without any prompting from the examiner. Thus, this task also indirectly tests the students’ executive function abilities in addition to their phonemic awareness skills.

3. The Story Retelling (SR) subtest (description above) requires students to do just that retell a story. Be mindful of the fact that the presented stories have reduced complexity. Thus, unless the students possess significant retelling deficits, the above subtest may not capture their true retelling abilities. Recommendation: Consider supplementing this subtest with informal narrative measures. For younger children (kindergarten and first grade) I recommend using wordless picture books to perform a dynamic assessment of their retelling abilities following a clinician’s narrative model (e.g., HERE). For early elementary aged children (grades 2 and up), I recommend using picture books, which are first read to and then retold by the students with the benefit of pictorial but not written support. Finally, for upper elementary aged children (grades 4 and up), it may be helpful for the students to retell a book or a movie seen recently (or liked significantly) by them without the benefit of visual support all together (e.g., HERE).

4. The Nonword Repetition (NR) subtest (description above) requires students to repeat nonsense words of increasing length and complexity. Weaknesses in the area of nonword repetition have consistently been associated with language impairments and learning disabilities due to the task’s heavy reliance on phonological segmentation as well as phonological and lexical knowledge (Leclercq, Maillart, Majerus, 2013). Thus, both monolingual and simultaneously bilingual children with language and literacy impairments will be observed to present with patterns of segment substitutions (subtle substitutions of sounds and syllables in presented nonsense words) as well as segment deletions of nonword sequences more than 2-3 or 3-4 syllables in length (depending on the child’s age).

5. The Nonword Spelling (NS) subtest (description above) requires the students to spell nonwords from the Nonword Repetition (NR) subtest. Consequently, the Nonword Repetition (NR) subtest needs to be administered prior to the administration of this subtest in the same assessment session. In contrast to the real-word spelling tasks, students cannot memorize the spelling of the presented words, which are still bound by orthographic and phonotactic constraints of the English language. While this is a highly useful subtest, is important to note that simultaneously bilingual children may present with decreased scores due to vowel errors. Consequently, it is important to analyze subtest results in order to determine whether dialectal differences rather than a presence of an actual disorder is responsible for the error patterns.

6. The Listening Comprehension (LC) subtest (description above) requires the students to listen to short stories and then definitively answer story questions via available answer choices, which include: “Yes”, “No’, and “Maybe”. This subtest also indirectly measures the students’ metalinguistic awareness skills as they are needed to detect when the text does not provide sufficient information to answer a particular question definitively (e.g., “Maybe” response may be called for). Be mindful of the fact that because the students are not expected to provide sentential responses to questions it may be important to supplement subtest administration with another listening comprehension assessment. Tests such as the Listening Comprehension Test-2 (LCT-2), the Listening Comprehension Test-Adolescent (LCT-A), or the Executive Function Test-Elementary (EFT-E) may be useful if language processing and listening comprehension deficits are suspected or reported by parents or teachers. This is particularly important to do with students who may be ‘good guessers’ but who are also reported to present with word-finding difficulties at sentence and discourse levels.

7. The Reading Comprehension (RC) subtest (description above) requires the students to read short story and answer story questions in “Yes”, “No’, and “Maybe” format. This subtest is not stand alone and must be administered immediately following the administration the Listening Comprehension subtest. The student is asked to read the first story out loud in order to determine whether s/he can proceed with taking this subtest or discontinue due to being an emergent reader. The criterion for administration of the subtest is making 7 errors during the reading of the first story and its accompanying questions. Unfortunately, in my clinical experience this subtest is not always accurate at identifying children with reading-based deficits.

While I find it terrific for students with severe-profound reading deficits and/or below average IQ, a number of my students with average IQ and moderately impaired reading skills managed to pass it via a combination of guessing and luck despite being observed to misread aloud between 40-60% of the presented words. Be mindful of the fact that typically such students may have up to 5-6 errors during the reading of the first story. Thus, according to administration guidelines these students will be allowed to proceed and take this subtest. They will then continue to make text misreadings during each story presentation (you will know that by asking them to read each story aloud vs. silently). However, because the response mode is in definitive (“Yes”, “No’, and “Maybe”) vs. open ended question format, a number of these students will earn average scores by being successful guessers. Recommendation: I highly recommend supplementing the administration of this subtest with grade level (or below grade level) texts (see HERE and/or HERE), to assess the student’s reading comprehension informally.

I present a full one page text to the students and ask them to read it to me in its entirety. I audio/video record the student’s reading for further analysis (see Reading Fluency section below). After the completion of the story I ask the student questions with a focus on main idea comprehension and vocabulary definitions. I also ask questions pertaining to story details. Depending on the student’s age I may ask them abstract/ factual text questions with and without text access. Overall, I find that informal administration of grade level (or even below grade-level) texts coupled with the administration of standardized reading tests provides me with a significantly better understanding of the student’s reading comprehension abilities rather than administration of standardized reading tests alone.

8. The Following Directions (FD) subtest (description above) measures the student’s ability to execute directions of increasing length and complexity. It measures the student’s short-term, immediate and working memory, as well as their language comprehension. What is interesting about the administration of this subtest is that the graphic symbols (e.g., objects, shapes, letter and numbers etc.) the student is asked to modify remain covered as the instructions are given (to prevent visual rehearsal). After being presented with the oral instruction the students are expected to move the card covering the stimuli and then to executive the visual-spatial, directional, sequential, and logical if–then the instructions by marking them on the response form. The fact that the visual stimuli remains covered until the last moment increases the demands on the student’s memory and comprehension. The subtest was created to simulate teacher’s use of procedural language (giving directions) in classroom setting (as per developers).

9. The Delayed Story Retelling (DSR) subtest (description above) needs to be administered to the students during the same session as the Story Retelling (SR) subtest, approximately 20 minutes after the SR subtest administration. Despite the relatively short passage of time between both subtests, it is considered to be a measure of long-term memory as related to narrative retelling of reduced complexity. Here, the examiner can compare student’s performance to determine whether the student did better or worse on either of these measures (e.g., recalled more information after a period of time passed vs. immediately after being read the story). However, as mentioned previously, some students may recall this previously presented story fairly accurately and as a result may obtain an average score despite a history of teacher/parent reported long-term memory limitations. Consequently, it may be important for the examiner to supplement the administration of this subtest with a recall of a movie/book recently seen/read by the student (a few days ago) in order to compare both performances and note any weaknesses/limitations.

10. The Nonword Reading (NR) subtest (description above) requires students to decode nonsense words of increasing length and complexity. What I love about this subtest is that the students are unable to effectively guess words (as many tend to routinely do when presented with real words). Consequently, the presentation of this subtest will tease out which students have good letter/sound correspondence abilities as well as solid orthographic, morphological and phonological awareness skills and which ones only memorized sight words and are now having difficulty decoding unfamiliar words as a result.

11. The Reading Fluency (RF) subtest (description above) requires students to efficiently read facts which make up simple stories fluently and correctly. Here are the key to attaining an average score is accuracy and automaticity. In contrast to the previous subtest, the words are now presented in meaningful simple syntactic contexts.

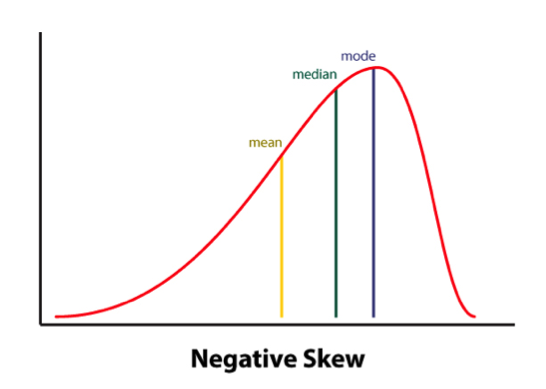

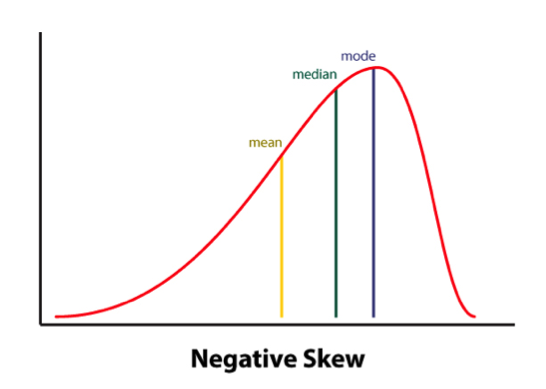

It is important to note that the Reading Fluency subtest of the TILLS has a negatively skewed distribution. As per authors, “a large number of typically developing students do extremely well on this subtest and a much smaller number of students do quite poorly.”

Thus, “the mean is to the left of the mode” (see publisher’s image below). This is why a student could earn an average standard score (near the mean) and a low percentile rank when true percentiles are used rather than NCE percentiles (Normal Curve Equivalent).

Consequently under certain conditions (See HERE) the percentile rank (vs. the NCE percentile) will be a more accurate representation of the student’s ability on this subtest.

Indeed, due to the reduced complexity of the presented words some students (especially younger elementary aged) may obtain average scores and still present with serious reading fluency deficits.

I frequently see that in students with average IQ and go to long-term memory, who by second and third grades have managed to memorize an admirable number of sight words due to which their deficits in the areas of reading appeared to be minimized. Recommendation: If you suspect that your student belongs to the above category I highly recommend supplementing this subtest with an informal measure of reading fluency. This can be done by presenting to the student a grade level text (I find science and social studies texts particularly useful for this purpose) and asking them to read several paragraphs from it (see HERE and/or HERE).

As the students are reading I calculate their reading fluency by counting the number of words they read per minute. I find it very useful as it allows me to better understand their reading profile (e.g, fast/inaccurate reader, slow/inaccurate reader, slow accurate reader, fast/accurate reader). As the student is reading I note their pauses, misreadings, word-attack skills and the like. Then, I write a summary comparing the students reading fluency on both standardized and informal assessment measures in order to document students strengths and limitations.

12. The Written Expression (WE) subtest (description above) needs to be administered to the students immediately after the administration of the Reading Fluency (RF) subtest because the student is expected to integrate a series of facts presented in the RF subtest into their writing sample. There are 4 stories in total for the 4 different age groups.

The examiner needs to show the student a different story which integrates simple facts into a coherent narrative. After the examiner reads that simple story to the students s/he is expected to tell the students that the story is okay, but “sounds kind of “choppy.” They then need to show the student an example of how they could put the facts together in a way that sounds more interesting and less choppy by combining sentences (see below). Finally, the examiner will ask the students to rewrite the story presented to them in a similar manner (e.g, “less choppy and more interesting.”)

After the student finishes his/her story, the examiner will �analyze it and generate the following scores: a discourse score, a sentence score, and a word score. Detailed instructions as well as the Examiner’s Practice Workbook are provided to assist with scoring as it takes a bit of training as well as trial and error to complete it, especially if the examiners are not familiar with certain procedures (e.g., calculating T-units).

Full disclosure: Because the above subtest is still essentially sentence combining, I have only used this subtest a handful of times with my students. Typically when I’ve used it in the past, most of my students fell in two categories: those who failed it completely by either copying text word for word, failing to generate any written output etc. or those who passed it with flying colors but still presented with notable written output deficits. Consequently, I’ve replaced Written Expression subtest administration with the administration of written standardized tests, which I supplement with an informal grade level expository, persuasive, or narrative writing samples.

Having said that many clinicians may not have the access to other standardized written assessments, or lack the time to administer entire standardized written measures (which may frequently take between 60 to 90 minutes of administration time). Consequently, in the absence of other standardized writing assessments, this subtest can be effectively used to gauge the student’s basic writing abilities, and if needed effectively supplemented by informal writing measures (mentioned above).

13. The Social Communication (SC) subtest (description above) assesses the students’ ability to understand vocabulary associated with communicative intentions in social situations. It requires students to comprehend how people with certain characteristics might respond in social situations by formulating responses which fit the social contexts of those situations. Essentially students become actors who need to act out particular scenes while viewing select words presented to them.

Full disclosure: Similar to my infrequent administration of the Written Expression subtest, I have also administered this subtest very infrequently to students. Here is why.

I am an SLP who works full-time in a psychiatric hospital with children diagnosed with significant psychiatric impairments and concomitant language and literacy deficits. As a result, a significant portion of my job involves comprehensive social communication assessments to catalog my students’ significant deficits in this area. Yet, past administration of this subtest showed me that number of my students can pass this subtest quite easily despite presenting with notable and easily evidenced social communication deficits. Consequently, I prefer the administration of comprehensive social communication testing when working with children in my hospital based program or in my private practice, where I perform independent comprehensive evaluations of language and literacy (IEEs).

Again, as I’ve previously mentioned many clinicians may not have the access to other standardized social communication assessments, or lack the time to administer entire standardized written measures. Consequently, in the absence of other social communication assessments, this subtest can be used to get a baseline of the student’s basic social communication abilities, and then be supplemented with informal social communication measures such as the Informal Social Thinking Dynamic Assessment Protocol (ISTDAP) or observational social pragmatic checklists.

14. The Digit Span Forward (DSF) subtest (description above) is a relatively isolated measure of short term and verbal working memory ( it minimizes demands on other aspects of language such as syntax or vocabulary).

15. The Digit Span Backward (DSB) subtest (description above) assesses the student’s working memory and requires the student to mentally manipulate the presented stimuli in reverse order. It allows examiner to observe the strategies (e.g. verbal rehearsal, visual imagery, etc.) the students are using to aid themselves in the process. Please note that the Digit Span Forward subtest must be administered immediately before the administration of this subtest.

SLPs who have used tests such as the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals – 5 (CELF-5) or the Test of Auditory Processing Skills – Third Edition (TAPS-3) should be highly familiar with both subtests as they are fairly standard measures of certain aspects of memory across the board.

To continue, in addition to the presence of subtests which assess the students literacy abilities, the TILLS also possesses a number of interesting features.

For starters, the TILLS Easy Score, which allows the examiners to use their scoring online. It is incredibly easy and effective. After clicking on the link and filling out the preliminary demographic information, all the examiner needs to do is to plug in this subtest raw scores, the system does the rest. After the raw scores are plugged in, the system will generate a PDF document with all the data which includes (but is not limited to) standard scores, percentile ranks, as well as a variety of composite and core scores. The examiner can then save the PDF on their device (laptop, PC, tablet etc.) for further analysis.

The there is the quadrant model. According to the TILLS sampler (HERE) “it allows the examiners to assess and compare students’ language-literacy skills at the sound/word level and the sentence/ discourse level across the four oral and written modalities—listening, speaking, reading, and writing” and then create “meaningful pro�files of oral and written language skills that will help you understand the strengths and needs of individual students and communicate about them in a meaningful way with teachers, parents, and students. (pg. 21)”

Then there is the Student Language Scale (SLS) which is a one page checklist parents, teachers (and even students) can fill out to informally identify language and literacy based strengths and weaknesses. It allows for meaningful input from multiple sources regarding the students performance (as per IDEA 2004) and can be used not just with TILLS but with other tests or in even isolation (as per developers).

Furthermore according to the developers, because the normative sample included several special needs populations, the TILLS can be used with students diagnosed with ASD, deaf or hard of hearing (see caveat), as well as intellectual disabilities (as long as they are functioning age 6 and above developmentally).

According to the developers the TILLS is aligned with Common Core Standards and can be administered as frequently as two times a year for progress monitoring (min of 6 mos post 1st administration).

With respect to bilingualism examiners can use it with caution with simultaneous English learners but not with sequential English learners (see further explanations HERE). Translations of TILLS are definitely not allowed as they will undermine test validity and reliability.

So there you have it these are just some of my very few impressions regarding this test. Now to some of you may notice that I spend a significant amount of time pointing out some of the tests limitations. However, it is very important to note that we have research that indicates that there is no such thing as a “perfect standardized test” (see HERE for more information). All standardized tests have their limitations.

Having said that, I think that TILLS is a PHENOMENAL addition to the standardized testing market, as it TRULY appears to assess not just language but also literacy abilities of the students on our caseloads.

That’s all from me; however, before signing off I’d like to provide you with more resources and information, which can be reviewed in reference to TILLS. For starters, take a look at Brookes Publishing TILLS resources. These include (but are not limited to) TILLS FAQ, TILLS Easy-Score, TILLS Correction Document, as well as 3 FREE TILLS Webinars. There’s also a Facebook Page dedicated exclusively to TILLS updates (HERE).

But that’s not all. Dr. Nelson and her colleagues have been tirelessly lecturing about the TILLS for a number of years, and many of their past lectures and presentations are available on the ASHA website as well as on the web (e.g., HERE, HERE, HERE, etc). Take a look at them as they contain far more in-depth information regarding the development and implementation of this groundbreaking assessment.

To access TILLS fully-editable template, click HERE

Disclaimer: I did not receive a complimentary copy of this assessment for review nor have I received any encouragement or compensation from either Brookes Publishing or any of the TILLS developers to write it. All images of this test are direct property of Brookes Publishing (when clicked on all the images direct the user to the Brookes Publishing website) and were used in this post for illustrative purposes only.

References:

Leclercq A, Maillart C, Majerus S. (2013) Nonword repetition problems in children with SLI: A deficit in accessing long-term linguistic representations? Topics in Language Disorders. 33 (3) 238-254.

Related Posts:

When many of us think of such labels as “language disorder” or “learning disability”, very infrequently do adolescents (students 13-18 years of age) come to mind. Even today, much of the research in the field of pediatric speech pathology involves preschool and school-aged children under 12 years of age.

When many of us think of such labels as “language disorder” or “learning disability”, very infrequently do adolescents (students 13-18 years of age) come to mind. Even today, much of the research in the field of pediatric speech pathology involves preschool and school-aged children under 12 years of age.

In July 2015 I wrote a blog post entitled: “Why (C) APD Diagnosis is NOT Valid!”

In July 2015 I wrote a blog post entitled: “Why (C) APD Diagnosis is NOT Valid!” As an SLP who routinely conducts speech and language assessments in several settings (e.g., school and private practice), I understand the utility of and the need for standardized speech, language, and literacy tests. However, as an SLP who works with children with dramatically varying degree of cognition, abilities, and skill-sets, I also highly value supplementing these standardized tests with functional and dynamic assessments, interactions, and observations.

As an SLP who routinely conducts speech and language assessments in several settings (e.g., school and private practice), I understand the utility of and the need for standardized speech, language, and literacy tests. However, as an SLP who works with children with dramatically varying degree of cognition, abilities, and skill-sets, I also highly value supplementing these standardized tests with functional and dynamic assessments, interactions, and observations. Since a significant value is placed on standardized testing by both schools and insurance companies for the purposes of service provision and reimbursement, I wanted to summarize in today’s post the findings of recent articles on this topic. Since my primary interest lies in assessing and treating school-age children, for the purposes of today’s post all of the reviewed articles came directly from the

Since a significant value is placed on standardized testing by both schools and insurance companies for the purposes of service provision and reimbursement, I wanted to summarize in today’s post the findings of recent articles on this topic. Since my primary interest lies in assessing and treating school-age children, for the purposes of today’s post all of the reviewed articles came directly from the  Turns out it did not! Turns out due to the variation in psychometric properties of various tests (

Turns out it did not! Turns out due to the variation in psychometric properties of various tests (

Thus they urged SLPs to exercise caution in determining the severity of children’s language impairment via norm-referenced test performance “given the inconsistency in guidelines and lack of empirical data within test manuals to support this use (176)”.

Thus they urged SLPs to exercise caution in determining the severity of children’s language impairment via norm-referenced test performance “given the inconsistency in guidelines and lack of empirical data within test manuals to support this use (176)”. But are the SLPs from across the country appropriately using the federal and state guidelines in order to determine eligibility?

But are the SLPs from across the country appropriately using the federal and state guidelines in order to determine eligibility? So where do we go from here? Well, it’s quite simple really! We already know what the problem is. Based on the above articles we know that:

So where do we go from here? Well, it’s quite simple really! We already know what the problem is. Based on the above articles we know that:

Wait a second, you might say! “Isn’t that a definition of ‘code-switching’?” And the answer is: “No!” The concept of ‘code-switching’ implies that bilinguals use two separate linguistic codes which do not overlap/reference each other. In contrast, ‘translanguaging’ assumes from the get-go that “bilinguals have one linguistic repertoire from which they select features strategically to communicate effectively” (Garcia, 2012, pg. 1). Bilinguals engage in translanguaging on an ongoing basis in their daily lives. They speak different languages to different individuals, find ‘Google’ translations of words and compare results from various online sites, listen to music in one language but watch TV in another, as well as watch TV announcers fluidly integrate several languages in their event narratives during news or in infomercials (Celic & Seltzer, 2011). For functional bilinguals, these practices are such integral part of their daily lives that they rarely realize just how much ‘translanguaging’ they actually do every day.

Wait a second, you might say! “Isn’t that a definition of ‘code-switching’?” And the answer is: “No!” The concept of ‘code-switching’ implies that bilinguals use two separate linguistic codes which do not overlap/reference each other. In contrast, ‘translanguaging’ assumes from the get-go that “bilinguals have one linguistic repertoire from which they select features strategically to communicate effectively” (Garcia, 2012, pg. 1). Bilinguals engage in translanguaging on an ongoing basis in their daily lives. They speak different languages to different individuals, find ‘Google’ translations of words and compare results from various online sites, listen to music in one language but watch TV in another, as well as watch TV announcers fluidly integrate several languages in their event narratives during news or in infomercials (Celic & Seltzer, 2011). For functional bilinguals, these practices are such integral part of their daily lives that they rarely realize just how much ‘translanguaging’ they actually do every day. One of the most useful features of translanguaging (and there are many) is that it assists with further development of bilinguals’ metalinguistic awareness abilities by allowing them to compare language practices as well as explicitly notice language features. Consequently, not only do speech-language pathologists (SLPs) need to be aware of translanguaging when working with culturally diverse clients, they can actually assist their clients make greater linguistic gains by embracing translanguaging practices. Furthermore, one does not have to be a bilingual SLP to incorporate translanguaging practices in the therapy room. Monolingual SLPs can certainly do it as well, and with a great degree of success.

One of the most useful features of translanguaging (and there are many) is that it assists with further development of bilinguals’ metalinguistic awareness abilities by allowing them to compare language practices as well as explicitly notice language features. Consequently, not only do speech-language pathologists (SLPs) need to be aware of translanguaging when working with culturally diverse clients, they can actually assist their clients make greater linguistic gains by embracing translanguaging practices. Furthermore, one does not have to be a bilingual SLP to incorporate translanguaging practices in the therapy room. Monolingual SLPs can certainly do it as well, and with a great degree of success. Here are some strategies of how this can be accomplished. Let us begin with bilingual SLPs who have the ability to do therapy in both languages. One great way to incorporate translanguaging in therapy is to alternate between English and the desired language (e.g., Spanish) throughout the session. Translanguaging strategies may include: using key vocabulary, grammar and syntax structures in both languages (side to side), alternating between English and Spanish websites when researching specific information (e.g., an animal habitats, etc.), asking students to take notes in both languages or combining two languages in one piece of writing. For younger preschool students, reading the same book, translated in another language is also a viable option as it increases their lexicon in both languages.

Here are some strategies of how this can be accomplished. Let us begin with bilingual SLPs who have the ability to do therapy in both languages. One great way to incorporate translanguaging in therapy is to alternate between English and the desired language (e.g., Spanish) throughout the session. Translanguaging strategies may include: using key vocabulary, grammar and syntax structures in both languages (side to side), alternating between English and Spanish websites when researching specific information (e.g., an animal habitats, etc.), asking students to take notes in both languages or combining two languages in one piece of writing. For younger preschool students, reading the same book, translated in another language is also a viable option as it increases their lexicon in both languages. Those SLPs who treat ESL students with language disorders and collaborate with ESL teachers can design thematic intervention with a focus on particular topics of interest. For example, during the month of April there’s increased attention on the topic of ‘human impact on the environment.’ Students can read texts on this topic in English and then use the internet to look up websites containing the information in their birth language. They can also listen to a translation or a summary of the English book in their birth language. Finally, they can make comparisons of human impact on the environment between United States and their birth/heritage countries.

Those SLPs who treat ESL students with language disorders and collaborate with ESL teachers can design thematic intervention with a focus on particular topics of interest. For example, during the month of April there’s increased attention on the topic of ‘human impact on the environment.’ Students can read texts on this topic in English and then use the internet to look up websites containing the information in their birth language. They can also listen to a translation or a summary of the English book in their birth language. Finally, they can make comparisons of human impact on the environment between United States and their birth/heritage countries. We can “Get to know our students” by displaying a world map in our therapy room/classroom and asking them to show us where they were born or came from (or where their family is from). We can label the map with our students’ names and photographs and provide them with the opportunity to discuss their culture and develop cultural connections. We can create a multilingual therapy room by using multilingual labels and word walls as well as sprinkling our English language therapy with words relevant to the students from their birth/heritage languages (e.g., songs and greetings, etc.).

We can “Get to know our students” by displaying a world map in our therapy room/classroom and asking them to show us where they were born or came from (or where their family is from). We can label the map with our students’ names and photographs and provide them with the opportunity to discuss their culture and develop cultural connections. We can create a multilingual therapy room by using multilingual labels and word walls as well as sprinkling our English language therapy with words relevant to the students from their birth/heritage languages (e.g., songs and greetings, etc.).

Last week I wrote a blog post entitled: “

Last week I wrote a blog post entitled: “ Punctuation brings written words to life. As we have seen from countless of grammar memes, an error in punctuation results in conveying a completely different meaning.

Punctuation brings written words to life. As we have seen from countless of grammar memes, an error in punctuation results in conveying a completely different meaning. This explicit instruction of punctuation terminology does significantly improve my students understanding of sentence formation. Even my students with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities significantly benefit from understanding how to use periods, commas and question marks in sentences.

This explicit instruction of punctuation terminology does significantly improve my students understanding of sentence formation. Even my students with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities significantly benefit from understanding how to use periods, commas and question marks in sentences. This in turns becomes a critical thinking and an executive functions activity. Students need sift through quite a bit of information to find a website which provides the clearest answers regarding the usage of specific punctuation marks. Here, it’s important for students to locate kid friendly websites which will provide them with simple but accurate descriptions of punctuation marks usage. One example of such website is

This in turns becomes a critical thinking and an executive functions activity. Students need sift through quite a bit of information to find a website which provides the clearest answers regarding the usage of specific punctuation marks. Here, it’s important for students to locate kid friendly websites which will provide them with simple but accurate descriptions of punctuation marks usage. One example of such website is  In my therapy sessions I spend a significant amount of time improving literacy skills (reading, spelling, and writing) of language impaired students. In my work with these students I emphasize goals with a focus on phonics, phonological awareness, encoding (spelling) etc. However, what I have frequently observed in my sessions are significant gaps in the students’ foundational knowledge pertaining to the basics of sound production and letter recognition. Basic examples of these foundational deficiencies involve students not being able to fluently name the letters of the alphabet, understand the difference between vowels and consonants, or fluently engage in sound/letter correspondence tasks (e.g., name a letter and then quickly and accurately identify which sound it makes). Consequently, a significant portion of my sessions involves explicit instruction of the above concepts.

In my therapy sessions I spend a significant amount of time improving literacy skills (reading, spelling, and writing) of language impaired students. In my work with these students I emphasize goals with a focus on phonics, phonological awareness, encoding (spelling) etc. However, what I have frequently observed in my sessions are significant gaps in the students’ foundational knowledge pertaining to the basics of sound production and letter recognition. Basic examples of these foundational deficiencies involve students not being able to fluently name the letters of the alphabet, understand the difference between vowels and consonants, or fluently engage in sound/letter correspondence tasks (e.g., name a letter and then quickly and accurately identify which sound it makes). Consequently, a significant portion of my sessions involves explicit instruction of the above concepts. So I do! Furthermore, I can tell you that explicit instruction of metalinguistic vocabulary does significantly improve my students understanding of the tasks involved in obtaining literacy competence. Even my students with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities significantly benefit from understanding the meanings of: letters, words, sentences, etc.

So I do! Furthermore, I can tell you that explicit instruction of metalinguistic vocabulary does significantly improve my students understanding of the tasks involved in obtaining literacy competence. Even my students with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities significantly benefit from understanding the meanings of: letters, words, sentences, etc. A word of caution as though regarding using

A word of caution as though regarding using

Here is the problem though: I only see the above follow-up steps in a small percentage of cases. In the vast majority of cases in which score discrepancies occur, I see the examiners ignoring the weaknesses without follow up. This of course results in the child not qualifying for services.

Here is the problem though: I only see the above follow-up steps in a small percentage of cases. In the vast majority of cases in which score discrepancies occur, I see the examiners ignoring the weaknesses without follow up. This of course results in the child not qualifying for services. So the next time you see a pattern of strengths and weaknesses and testing, even if it amounts to a total average score, I urge you to dig deeper. I urge you to investigate why this pattern is displayed in the first place. The same goes for you – parents! If you are looking at average total scores but seeing unexplained weaknesses in select testing areas, start asking questions! Ask the professional to explain why those deficits are occuring and tell them to dig deeper if you are not satisfied with what you are hearing. All students deserve access to FAPE (Free and Appropriate Public Education). This includes access to appropriate therapies, they may need in order to optimally function in the classroom.

So the next time you see a pattern of strengths and weaknesses and testing, even if it amounts to a total average score, I urge you to dig deeper. I urge you to investigate why this pattern is displayed in the first place. The same goes for you – parents! If you are looking at average total scores but seeing unexplained weaknesses in select testing areas, start asking questions! Ask the professional to explain why those deficits are occuring and tell them to dig deeper if you are not satisfied with what you are hearing. All students deserve access to FAPE (Free and Appropriate Public Education). This includes access to appropriate therapies, they may need in order to optimally function in the classroom. “Well, the school did their evaluations and he doesn’t qualify for services” tells me a parent of a 3.5 year old, newly admitted private practice client. “I just don’t get it” she says bemusedly, “It is so obvious to anyone who spends even 10 minutes with him that his language is nowhere near other kids his age!” “How can this happen?” she asks frustratedly?

“Well, the school did their evaluations and he doesn’t qualify for services” tells me a parent of a 3.5 year old, newly admitted private practice client. “I just don’t get it” she says bemusedly, “It is so obvious to anyone who spends even 10 minutes with him that his language is nowhere near other kids his age!” “How can this happen?” she asks frustratedly?

As per NJAC 6A:14-2.5

As per NJAC 6A:14-2.5  These delays can be receptive (listening) or expressive (speaking) and need not be based on a total test score but rather on all testing findings with a minimum of at least two assessments being performed. A determination of adverse impact in academic and non-academic areas (e.g., social functioning) needs to take place in order for special education and related services be provided. Additionally, a delay in articulation can serve as a basis for consideration of eligibility as well.

These delays can be receptive (listening) or expressive (speaking) and need not be based on a total test score but rather on all testing findings with a minimum of at least two assessments being performed. A determination of adverse impact in academic and non-academic areas (e.g., social functioning) needs to take place in order for special education and related services be provided. Additionally, a delay in articulation can serve as a basis for consideration of eligibility as well. General Language:

General Language:  Pragmatics/Social Communication

Pragmatics/Social Communication Finally, by showing children simple

Finally, by showing children simple