Assessment of children with DS syndrome is often complicated due to the wide spectrum of presenting deficits (e.g., significant health issues in conjunction with communication impairment, lack of expressive language, etc) making accurate assessment of their communication a difficult task. In order to provide these children with appropriate therapy services via the design of targeted goals and objectives, we need to create comprehensive assessment procedures that focus on highlighting their communicative strengths and not just their deficits.

Assessment of children with DS syndrome is often complicated due to the wide spectrum of presenting deficits (e.g., significant health issues in conjunction with communication impairment, lack of expressive language, etc) making accurate assessment of their communication a difficult task. In order to provide these children with appropriate therapy services via the design of targeted goals and objectives, we need to create comprehensive assessment procedures that focus on highlighting their communicative strengths and not just their deficits.

Today I’d like to discuss assessment procedures for verbal monolingual and bilingual children with DS 4-9 years of age, since testing instruments as well as assessment procedures for younger as well as older verbal and nonverbal children with DS do differ.

When it comes to dual language use and genetic disorders and developmental disabilities many educational and health care professionals are still under the erroneous assumption that it is better to use one language (English) to communicate with these children at home and at school. However, studies have shown that not only can children with DS become functionally bilingual they can even become functionally trilingual (Vallar & Papagno, 1993; Woll & Grove, 1996). It is important to understand that “bilingualism does not change the general profile of language strengths and weaknesses characteristic of DS—most children with DS will have receptive vocabulary strengths and expressive language weaknesses, regardless of whether they are monolingual or bilingual.” (Kay-Raining Bird, 2009, p. 194)

Furthermore, advising a bilingual family to only speak English with a child will cause a number of negative linguistic and psychosocial implications, such as create social isolation from family members who may not speak English well as well as adversely affect parent-child relationships (Portes & Hao, 1998).

Consequently, when preparing to assess linguistic abilities of children with DS we need to first determine whether these children have single or dual language exposure and design assessment procedures accordingly.

Pre-assessment Considerations

It is very important to conduct a parental interview no matter the setting you are performing the assessment in. One of your goals during the interview will be to establish the functional goals the parents’ desire for the child which may not always coincide with the academic expectations of the program in question.

Begin with a detailed case history and review of current records and obtain information about the child’s prenatal, perinatal and postnatal development, medical history as well as the nature of previous assessments and provided related services. Next, obtain a detailed history of the child’s language use by inquiring what languages are spoken by household members and how much time do these people spend with the child?

Choosing Testing Instruments

A balanced assessment will include a variety of methods, including observations of the child as well as direct interactions in the form of standardized, informal and dynamic assessments. If you will be using standardized assessments (e.g., ROWPVT-4) YOU MUST use descriptive measures vs. standardized scores to describe the child’s functioning. The latter is especially applicable to bilingual children with DS. Consider using the following disclaimer: “The following test/s __________were normed on typically developing English speaking children. Testing materials are not available in standardized form for child’s unique developmental and bilingual/bicultural backgrounds. In accordance with IDEA 2004 (The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) [20 U.S.C.¤1414(3)],official use of standard scores for this child would be inaccurate and misleading so the results reported are presented in descriptive form. Raw scores are provided here only for comparison with future performance.”

Selecting Standardized Assessments

Depending on the child’s age and level of abilities a variety of assessment measures may be applicable to test the child in the areas of Content (vocabulary), Form (grammar/syntax), and Use(pragmatic language).

For children over 3 years of age whose linguistic abilities are just emerging you may wish to use a vocabulary inventory such as the MacArthur-Bates (also available in other languages) as well as provide parents with the Developmental Scale for Children with Down Syndrome to fill out. This will allow you to compare where child with DS features in their development as compared to typically developing peers. For older, more verbal children who are using words, phrases, and/or sentences to express themselves, you may want to use or adapt (see above) one of the following standardized language tests:

- Preschool Language Assessment Instrument-2 (PLAI-2)

- Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-Preschool 2 (CELF-P2)

- Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test-4 (ROWPVT)

- Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test-4 (EOWPVT)

- Test of Auditory Processing Skills-3 (TAPS-3)

- Narrative Assessment Protocol (NAP)

Informal Assessment Procedures

Depending on your setting (hospital vs. school), you may not perform a detailed assessment of the child’s feeding and swallowing skills. However, it is still important to understand that due to low muscle tone, respiratory problems, gastrointestinal disorders and cardiac issues, children with DSoften present with feeding dysfunction which is further exacerbated by concomitant issues such as obesity, GERD, constipation, malnutrition (restricted food group intake lacking in vitamins and minerals), and fatigue. With respect to swallowing, they may experience abnormalities in both the oral and pharyngeal phases of swallow, as well as present with silent aspiration, due to which instrumental assessment (MBS) may be necessary (Frazer & Friedman, 2006).

In contrast to feeding and swallowing the oral-peripheral assessment can be performed in all settings. When performing oral-peripheral exam, you need to carefully describe all structural (anatomical) and functional (physiological) abnormalities (e.g., macroglossia, micrognathia, prognathism, etc). Note any issues with:

- Dentition (e.g., dental overcrowding, occlusion, etc)

- Tongue/jaw disassociation (ability to separate tongue from jaw when speaking)

- Mouth Posture (open/closed) and tongue positioning at rest (protruding/retracted)

- Control of oral secretions

- Lingual and buccal strength, movement (e.g., lingual protrusion, elevation, lateralization, and depression for volitional tasks) and control

- Mandibular (jaw) strength, stability and grading

Take a careful look at the child’s speech. Perform dual speech sampling (if applicable) by considering the child’s phonetic inventory, syllable lengths and shapes as well as articulatory/phonological error patterns. Make sure to factor in the combined effect of the child’s craniofacial anomalies as well as system wide impairment (disturbances in respiration, voice, articulation, resonance, fluency, and prosody) on conversational intelligibility. Impaired intelligibility is a serious concern for individuals with DS, as it tends to persist throughout life for many of them and significantly interferes with social and vocational pursuits (Kent & Vorperian, 2013)

Don’t forget to assess the child’s voice, fluency, prosody, and resonance. Children with DS may have difficulty maintaining constant airstream for vocal production due to which they may occasionally speak with low vocal volume and breathiness (caused by air loss due to vocal fold hypotonicity). This may be directly targeted in treatment sessions and taught how to compensate for. When assessing resonance make sure to screen the child for hypernasality which may be due to velopharyngeal insufficiency secondary to hypotonicity as well as rule out hyponasality which may be due to enlarged adenoids (Kent & Vorperian, 2013). Furthermore, since stuttering and cluttering occur in children with DS at rates of 10 to 45%, compared to about 1% in the general population, a detailed analysis of disfluencies may be necessary(Kent & Vorperian, 2013). Finally, due to limitations with perception, imitation, and spontaneous production of prosodic features secondary to motor difficulties, motor coordination issues, and segmental errors that impede effective speech production across multisyllabic sequences, the prosody of individuals with DS will be impaired and might require a separate intervention. (Kent & Vorperian, 2013)

When it comes to auditory function, formal hearing testing and retesting is mandatory due to the fact that many children with DS have high prevalence of conductive and sensorineural hearing loss (Park et al, 2012). So if the child in question is not receiving regular follow-ups from the audiologist, it is very important to make the appropriate referral. Similarly, it is also very important that the child’s visual perception is assessed as well since children with DS frequently experience difficulties with vision acuity as well as visual processing, consequentially a consultation with developmental optometrist may be recommended/needed.

Describe in detail the child’s adaptive behavior and learning style, including their social strengths and weaknesses. Observe the child’s eye contact, affect, attention to task, level of distractibility, and socialization patterns. Document the number of redirections and negotiations the child needed to participate as well as types and level of reinforcement used during testing.

Perform dual language sampling and look at functional vocabulary knowledge and use, grammar measures, sentence length, as well as the child’s pragmatic functions (what is the child using his/her language for: request, reject, comment, etc.) Perform a dynamic assessment to determine the child’s learnability (e.g., how quickly does the child learns and adapts to being taught new concepts?) since “even a minimal mediation in the form of ‘focusing’ improves the receptive language performance of children with DS” (Alony & Kozulin, 2007, p 323)

After all the above sections are completed, it is time to move on to the impressions section of the report. While it is important to document the weaknesses exposed by the assessment, it is even more important to document the child’s strengths or all the things the child did well, since this will help you to determine the starting treatment point and allow you to formulate relevant treatment goals.

When making recommendations for treatment, especially for bilingual children with DS, make sure to provide a strong rationale for the provision of services in both languages (if applicable) as well as specify the importance of continued support of the first language in the home.

Finally, make sure to provide targeted and measurable [suggested] treatment goals by breaking the targets into measurable parts:

Given ___time period (1 year, 1 progress reporting period, etc), the student will be able to (insert specific goal) with ___accuracy/trials, given ___ level of, given _____type of prompts.

Assessing communication abilities of children with developmental disabilities may not be easy; however, having the appropriate preparation and training will ensure that you will be well prepared to do the job right! Use multiple tasks and activities to create a balanced assessment, use descriptive measures instead of standard scores to report findings, and most importantly make your assessment functional by making sure that your testing yields relevant diagnostic information which could then be effectively used to provide effective quality treatments for clients with DS!

For comprehensive information on “Comprehensive Assessment of Monolingual and Bilingual Children with Down Syndrome” which discusses how to assess young (birth-early elementary age) verbal and nonverbal monolingual and bilingual children with Down Syndrome (DS) and offers comprehensive examples of write-ups based on real-life clients click HERE.

In my social pragmatic language groups I target a wide variety of social communication goals for children with varying levels and degrees of impairment with a focus on improving their social pragmatic language competence. In the past I have written blog posts on a variety of social pragmatic language therapy topics, including strategies for

In my social pragmatic language groups I target a wide variety of social communication goals for children with varying levels and degrees of impairment with a focus on improving their social pragmatic language competence. In the past I have written blog posts on a variety of social pragmatic language therapy topics, including strategies for

Today I am reviewing an awesome social-pragmatic language app by

Today I am reviewing an awesome social-pragmatic language app by  A few weeks ago I reviewed the

A few weeks ago I reviewed the

I’ve been meaning to write this post for some time and have finally decided to do it now due to an increased prevalence of “non-traditional” treatment options available to parents of language impaired children.

I’ve been meaning to write this post for some time and have finally decided to do it now due to an increased prevalence of “non-traditional” treatment options available to parents of language impaired children.

There you have it: that’s what the harm is! The toll of these quack practices can be very significant and can go far beyond the financial. So the next time someone utters the statement: “What’s the Harm in That?” consider the above information in order to make the informed decisions regarding the treatment for the most vulnerable parties involved: the children in your care!

There you have it: that’s what the harm is! The toll of these quack practices can be very significant and can go far beyond the financial. So the next time someone utters the statement: “What’s the Harm in That?” consider the above information in order to make the informed decisions regarding the treatment for the most vulnerable parties involved: the children in your care! It’s on the tip of my tongue! How many times have you used this expression or heard it from other people. Oftentimes when we think of word-finding deficits we automatically think of it as an adult affliction, however, you would be surprised how many children including even very young children (4+ years of age) are affected by it. Did you know that “

It’s on the tip of my tongue! How many times have you used this expression or heard it from other people. Oftentimes when we think of word-finding deficits we automatically think of it as an adult affliction, however, you would be surprised how many children including even very young children (4+ years of age) are affected by it. Did you know that “ Many of my students with Developmental Language Disorders (DLD)

Many of my students with Developmental Language Disorders (DLD)  Today it is truly my pleasure to bring you a giveaway from Maria Del Duca of

Today it is truly my pleasure to bring you a giveaway from Maria Del Duca of

A to Z Jr– a game of early categorizations is recommended for players 5 – 10 years of age, but can be used with older children depending on their knowledge base. The object of the game is to cover all letters on your letter board by calling out words in specific categories before the timer runs out. This game can be used to

A to Z Jr– a game of early categorizations is recommended for players 5 – 10 years of age, but can be used with older children depending on their knowledge base. The object of the game is to cover all letters on your letter board by calling out words in specific categories before the timer runs out. This game can be used to  Tribond Jr – is another great game which purpose is to determine how 3 seemingly random items are related to one another. Good for older children 7-12 years of age it’s also great for problem solving and reasoning as some of the answers are not so straight forward (e.g., what do the clock, orange and circle have in common? Psst…they are all round)

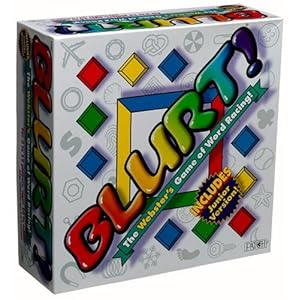

Tribond Jr – is another great game which purpose is to determine how 3 seemingly random items are related to one another. Good for older children 7-12 years of age it’s also great for problem solving and reasoning as some of the answers are not so straight forward (e.g., what do the clock, orange and circle have in common? Psst…they are all round) Blurt – a game for children 10 and up is a game that works on a simple premise. Blurt out as many answers as you can in order to guess what the word is. Blurt provides ready-made definitions that you read off to players so they could start guessing what the word is. Players and teams use squares on the board strategically to advance by competing in various definition challenges that increase language opportunities.

Blurt – a game for children 10 and up is a game that works on a simple premise. Blurt out as many answers as you can in order to guess what the word is. Blurt provides ready-made definitions that you read off to players so they could start guessing what the word is. Players and teams use squares on the board strategically to advance by competing in various definition challenges that increase language opportunities. Guess Who (age 6+),

Guess Who (age 6+),  Guess Where (age 6+), and Mystery Garden (age 4+) are great for encouraging students to ask relevant questions in order to be the first to win the game. They are also terrific for encouraging reasoning skills. Questions have to be thought through carefully in order to be the first one to win the game.

Guess Where (age 6+), and Mystery Garden (age 4+) are great for encouraging students to ask relevant questions in order to be the first to win the game. They are also terrific for encouraging reasoning skills. Questions have to be thought through carefully in order to be the first one to win the game.  In 30 Second Mysteries kids need to use critical thinking and deductive reasoning in order to solve mysteriously sounding cases of everyday events. Each clue read aloud reveals more about the mystery and the trick is to solve it given the fewest number of clues in order to gain the most points.

In 30 Second Mysteries kids need to use critical thinking and deductive reasoning in order to solve mysteriously sounding cases of everyday events. Each clue read aloud reveals more about the mystery and the trick is to solve it given the fewest number of clues in order to gain the most points.